V-J Day: P-51 pilot Jerry Yellin recalls last mission of WWII

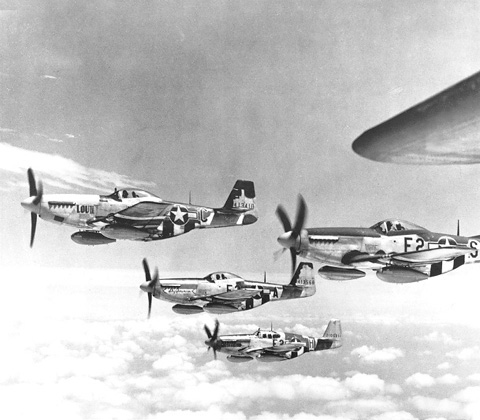

(P-51’s in flight in a )

September 2, 2015 marks seventy years since the official end of World War II. On that date in 1945, General Douglas MacArthur met a delegation of Japanese officials on the deck of the battleship USS Missouri for the formal signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender. But for most men in the field, the war had effectively ended two weeks earlier, when the word came that the Japanese leadership had at last said, ‘Enough’.

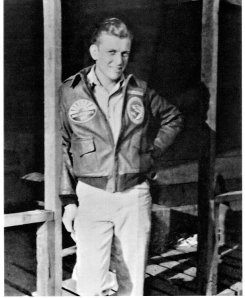

Captain Jerry Yellin was a P-51 fighter pilot assigned to the 78th Fighter Squadron, US Army Air Corps. The morning of August 14, 1945, Yellin led his men on what would be the last combat mission over Japan. Yellin survived that flight, but his war didn’t end, as he returned home to battle what is known today as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Now 90, the author of four books, and still active caring for a new generation of traumatized veterans, Yellin is set to receive a special honor this September 15 from the Air Force Association in Washington, DC. The Baltimore Post-Examiner caught up with Captain Yellin on the eve of V-J Day to talk about some of his wartime and post-war experiences.

BPE: Thank you for taking some time to speak with us today. We had a chance to chat briefly back in 2014 at the MAAM WWII Weekend. Would you please tell our readers about your service. What years were you in the Air Corps and what did you fly?

Yellin: I enlisted on my eighteenth birthday, two months after Pearl Harbor was bombed. After graduating from Luke Air Field, they sent me to Pearl Harbor to join the 78th Fighter Squadron, and to get more hours in a P-40. They switched us over to P-47’s for more training and for support of a planned operation in the South Pacific. But in a series of battles, the US Navy shot down so many Japanese aircraft, the mission they were planning ahead of the invasion of the Philippines was scrubbed, so we were transitioned to P-51’s.

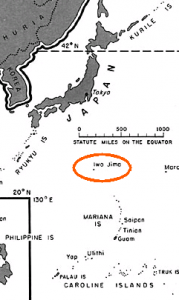

I eventually ended up going to an island we had never heard of called Iwo Jima. The Japanese weren’t on the island, they were in it. From there, once the Marines had secured that airfield, we were able to provide long range fighter protection to the B-29’s that were bombing Japan.

BPE: Do any missions stand out?

Yellin: Yes, the first and the last one. In between – what I mostly remember, are the sixteen men in my squadron who died on the various missions.

BPE: Would you tell us about that last mission?

Yellin: My last mission was on August 14, 1945. We had dropped the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki and were surprised the Japanese had still not surrendered. There was a thought that they could quit at any moment, and we even had a special code word – Ohio – for a recall if they surrendered once we were in the air. But our commanding officer, Lt. Colonel Jim Tapp, said we had to keep the Japanese honest, just in case, so we had to keep the pressure on them.

My mission that day was to strafe an airfield near Tokyo. But at the previous day’s briefing, my wing man – Lt. Phillip Schlamberg – said to me, “Captain, if we go, I’m not coming back.” I said, “What do you mean?” and he replied, “It’s just a feeling I have.” I told this to Jim Tapp, and he suggested Phil see a doctor, but he refused to go, so the next day we went on the mission. I told Phil, “Stay right on my wing, and you’ll be OK.”

We listened the entire way over, but we never heard the recall code.

We needed enough fuel to make our run, and ninety gallons to get back to our base. After strafing the field, I looked at my gauges to make sure I was OK, then I looked over at Phil and gave him the thumbs up. He returned the thumbs up, and I led our four planes up into a bank of clouds. When we came out of the clouds, Phil was gone. Nobody heard anything; nobody saw anything. When we landed on Iwo Jima, we found out that while we were strafing the airfield, the war had been over for three hours. So Phil Schlamberg was the last man to die on a combat mission during WWII.

By the way, Phil was the great-uncle of movie star Scarlett Johansson.

BPE: Prior to Hiroshima, and the subsequent Japanese surrender, wasn’t Washington planning a full scale invasion of Japan?

Yellin: Yes, and that would have been horrific given the tenacious nature of the Japanese people. Keep in mind that we didn’t consider the Japanese to be human. Anyone who goes to war has to be conditioned in their training to so hate the enemy that you see them as not being human. If they are human – how can you kill them? Men kill in war with guns, tanks, ships, bombs and grenades – anything you can think of. I killed with two 50 calibre machine guns mounted in my plane. If you behaved that way in civilian life, the authorities would want to kill you. But that is war and what it does to a man. That is why I suffered from PTSD.

BPE: PTSD is not a condition most associate with WWII veterans. The term I always heard when I was growing up was “shell shocked”.

Yellin: Yes, that and “battle fatigue”. But it’s all the same. I tried to bury it, but it took a toll on me and my family – especially my dear wife. Night after night I would think about the sixteen guys in my squadron who I saw die in battle.

BPE: You wrote a book about this?

Yellin: Yes, The Resilient Warrior, and I still speak to veteran’s groups about this issue.

BPE: What are your memories of V-J Day?

Yellin: When you say V-J Day, that would be August 14; the day the war actually ended. I know many consider September 2 the day, because that is when the official surrender was signed on the deck of the Missouri, but for most of us veterans, V-J Day is the day the fighting was finally over. But again, August 14 is bittersweet because of the loss of Phil Schlamberg.

BPE: You have a very interesting post-war story; particularly where it relates to family matters and your feelings for the Japanese people. Would you describe how that came about?

Yellin: In 1983, I was a consultant to some major banks in real estate. The Matsui Group wanted me to come to Japan. My initial reaction was that I didn’t want to go. I just wasn’t sure I could get over my hatred for the Japanese people, but my wife convinced me, so we went.

The last night we were there, my wife said, “We’ve loved Japan. Why don’t we give our son (who was a senior at San Diego State) a six week home stay in Japan.” That’s what we did. He graduated in 1984, but he didn’t know quite what to do, so he returned to Japan and took a job teaching English. Now it’s 31 years later, and he hasn’t come back.

We went back over there in 1987 because he asked us to come, and we were introduced to a young Japanese lady. He said he and this young lady wanted to get married, and I saw the faces of the sixteen guys I flew with flash through my mind. I thought, “Boy – what would they think?” But it was his life, not my life that was important, so I said to him, “What does her father say?” and he replied, “He won’t meet me.” I felt a little bit of relief that the girl’s father did not want to meet my son.

Seven months later, my son finally met the father, a man named Taro Yamakawa, along with two of his eldest sons and his daughter. The two brothers made my son promise them that if the couple were to marry, that my son would not take their sister away from Japan and that he would give her a good life.

The father then spoke and he asked my son five questions:

> “How old is your father?” My son said, “63.”

> “Was he in the war?” “Yes.”

> “What did he do?” “He was a pilot.”

> “What did he fly?” “P-51’s.”

> “Where?” “Over Japan.”

And that ended the meeting. The father went home and told his wife, “Make the wedding.” She went ballistic, screaming at her husband, saying, “For 43 years you’ve told me how much you hated Americans; that you are sorry you didn’t die trying to defeat them. And now you are saying you want our daughter to marry an American? Why?” He replied, “Any man who could fly a P-51 against the Japanese and live, must be a brave man. I want the blood of that man flowing through the veins of my grandchildren.” So on March 6 – nearly 43 years to the day that I landed on Iwo Jima, they got married. Today I have three Japanese grandchildren and I have three here in the States, but it’s all the same – my love for them and their love for me.

BPE: A lot has changed in the world since 1945. Seventy years after the end of WWII, how do you see society today?

Yellin: Here’s what I didn’t say before about the uniform. When you put that uniform on, you individually are pledging your life to protect the guys that you’re with. And they individually and collectively are pledging to give their lives to protect you. Only the people who put the uniform on and go into combat understand that. I think the police and firemen understand that as well, but they are also uniformed people.

But today, we have become a world that only cares about “me”. There was a purity of purpose in what we did seventy years ago. It was to eliminate evil. It was Britain, Russia and America which prevented Japan and Germany from ruling the world. We, as Americans, were all about “you” and “them” back then. Today, we are all about “me”.

The greatest adage is to live your life by what we all know as The Golden Rule. The Hebrew version – which I prefer – is translated as, “Do not do unto others what you would not have them do to you.” I think that is fitting. If people lived their lives that way, this world would be a much better place.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”

Regardless of how it is expressed, the golden rule is still the best approach to dealing with other people.