Baltimore Colts Glenn Doughty still Shakin’ and Bakin’

You might say the arc of Glenn “Shake & Bake” Doughty’s terrestrial pilgrimage bends toward pure performance, joyfully modeled, and celebrated in every arena he finds himself competing.

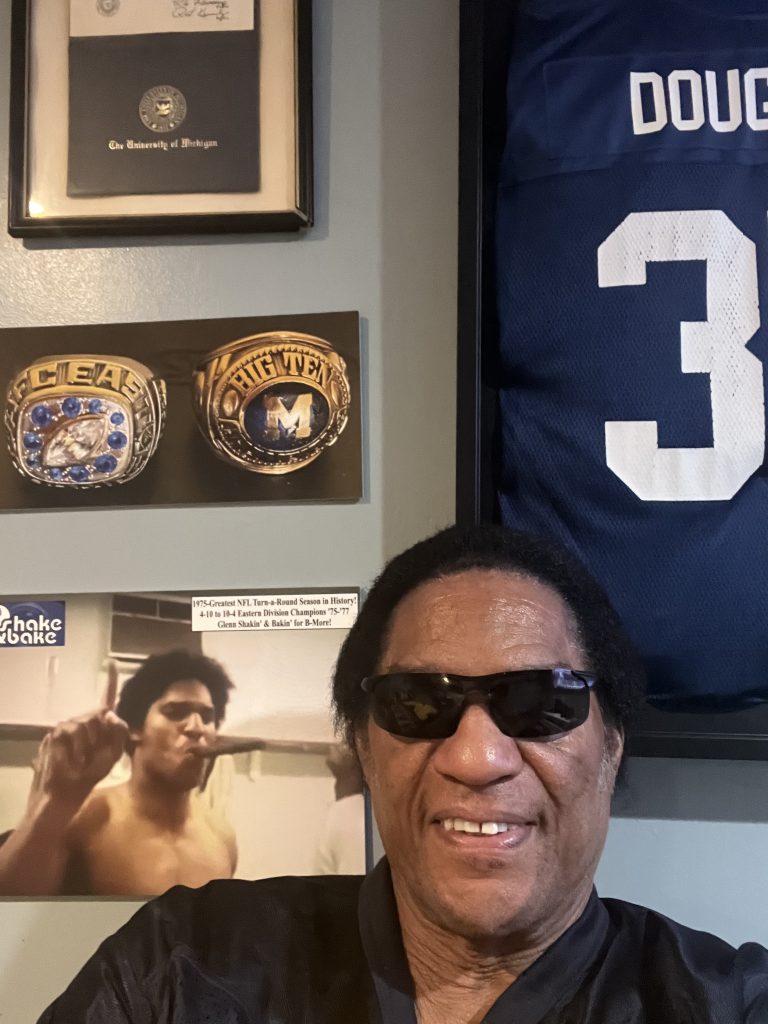

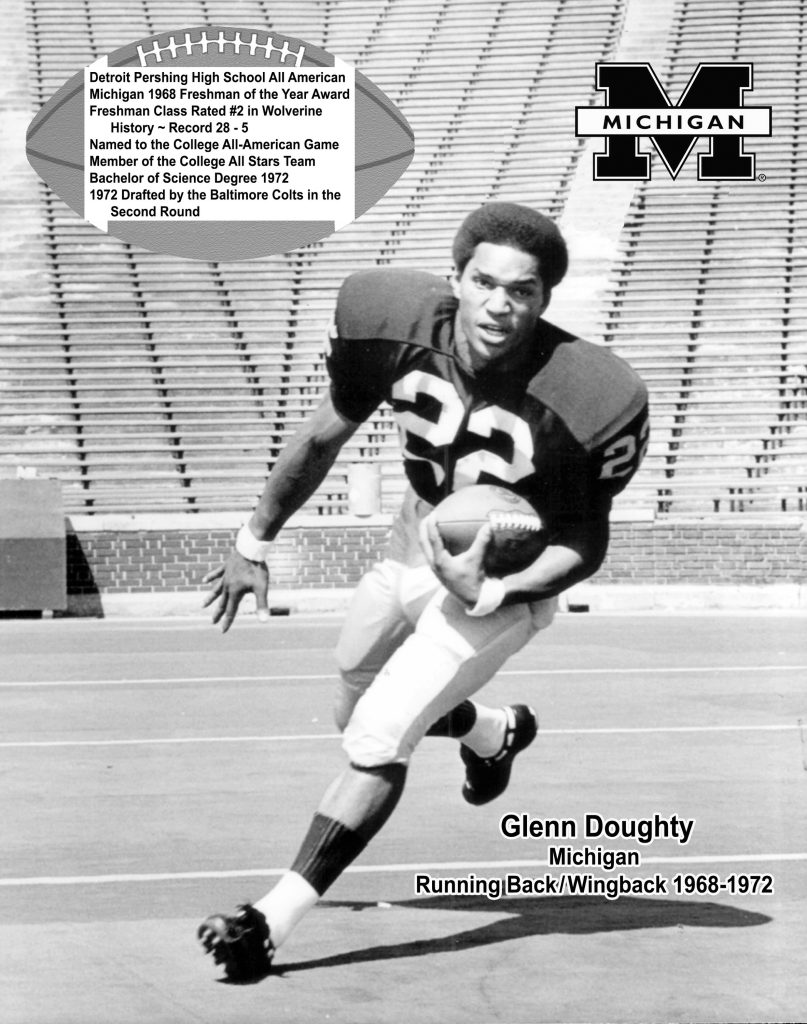

During his eight productive seasons as a wide receiver with the Baltimore Colts, Doughty caught 219 passes, scooted 24 touchdowns, and pocketed 3,547 career yards.

The former Michigan Wolverine standout was selected to the Pro Bowl and the Associated Press All-Pro, among other honors. In 1975, Doughty’s passion and physicality helped catapult the Colts from last to first place in the AFC East. It was the same year he set up The Shake & Bake Band with Colt teammates Freddie Scott, Ray Chester, and Lloyd Mumford.

During autumn Sundays at the old Memorial Stadium and on the road, number 35 endured his share of injuries. In a violent game, getting hurt is part and parcel of the on-field narrative. The list included a litany of orthopedic mishaps like torn Achilles. But the scariest, the one forever seared in his mind, he emphasized, related to one of the four concussions he endured.

“It was at a game in Denver,” Doughty, 72, told the Baltimore Post-Examiner. During a play, “my eye was pushed back into my socket. I cracked the cavity that held the eye itself. I was seeing double. The pain went all the way from my head to my foot. My whole body went numb.” His injury resulted in a trip to Johns Hopkins where doctors dislodged a piece of matter as long as 10 inches.

While that moment involved an area of the body that houses pupils, corneas, and irises, the experience enriched another kind of vision. one that nurtured the heart and soul–one that gave back to a marginalized community in Charm City. For Doughty, giving back is a calling. He’s all about preserving the rhythm he had honed as a standout athlete.

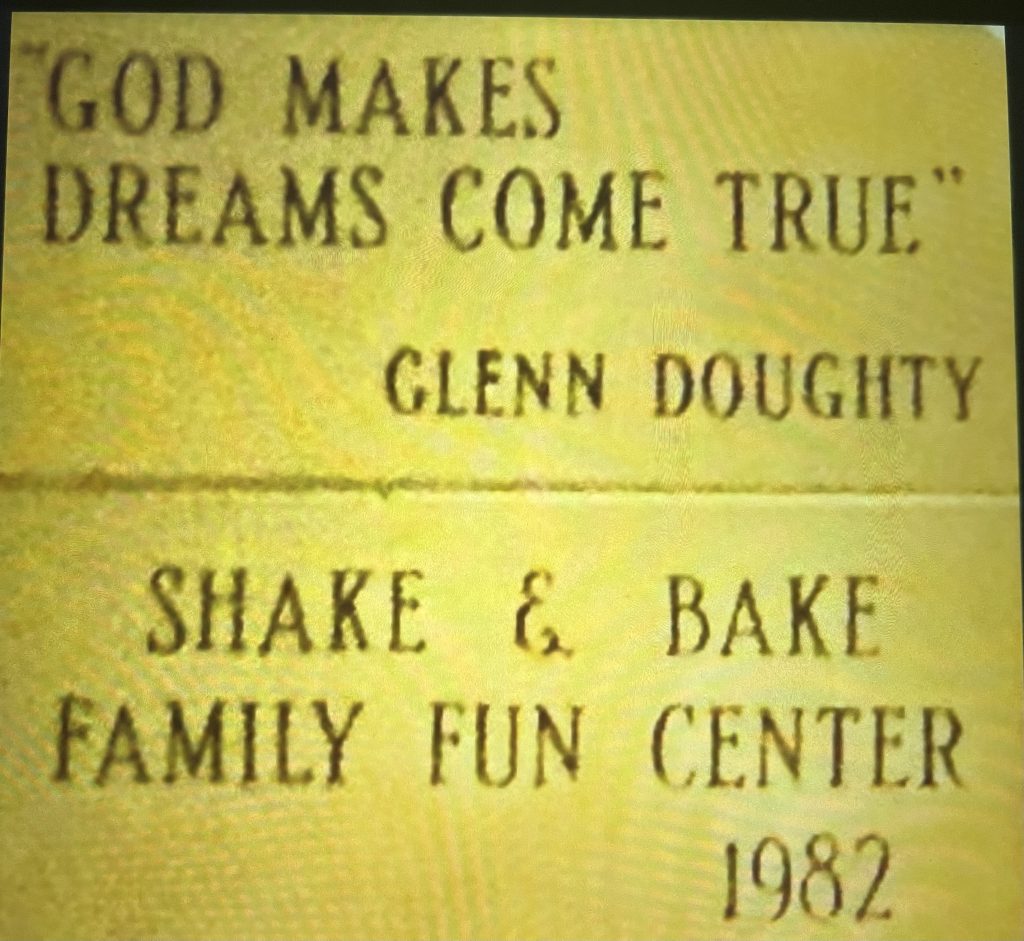

When he hung up his grass-stained cleats in 1980, hardly stopped number 35’s forward motion. By harnessing his outsized, sunny-side-up personality, Doughty had a playbook for life after football. His commitment: To leave West Baltimore and the Upton neighborhood a better place. That goal came to fruition in 1982, when Shake & Bake Family Fun Center opened its doors on Pennsylvania Avenue. While the iconic venue is now owned by the city’s Recreation and Parks Department, make no mistake: It’s Doughty’s thumbprints, his stylistic and breezy wholesomeness, that are enshrined there.

Baltimore and Shake & Bake kept Doughty busy. When he wasn’t greeting luminaries at the venue like Muhammed Ali and Eddie Kendricks, a lead singer of the Temptations, he hosted a regular program on Channel 13 during the offseason called Athlete of the Week. “Back then, you didn’t make the money in sports that you make now. You needed a Plan B.”

Personal recollections of his football glory days are always flavorfully layered with keen observations served sunny side up with generous helpings of hearty laughter.

It was Glenn’s electric personality that attracted others, asserted Billy Taylor, one of Dougherty’s teammates at the University of Michigan in the late 1960s. “He was outgoing and energetic, always pumped up, and very athletic. Clean cut, no vices.”

Taylor, a running back who shattered Michigan’s career rushing record, rolling up 3,072 yards in three seasons, recalled that he and Doughty helped compose a tight-knit, five-man squad that came to be known as “The Mellow Men.”

At that time, he said, the group represented the largest group of Black athletes on scholarship in Michigan’s history. Now 74, Taylor, who earned a PhD, said that back then, NCAA rules required freshmen athletes to live in dormitories on the sprawling Ann Arbor campus. “But in our sophomore year, we could move off campus. We decided we wanted to stick together and we found a six-bedroom house at 1345 Geddes Road. Glenn was one of the leaders of the house. He was more mature.”

Looking back on his days at Michigan and his fellow `Mellow Men,’ Doughty defined the deep relationships he enjoyed. “We clicked immediately. All of our abilities were evident to everybody who saw us.”

During that era, the country became saturated by anti-Vietnam War protests. The mood on the Ann Arbor campus reflected the restlessness. In the late 1960s, he explained, Michigan had only enrolled a handful of Black students. Dougherty, taking advantage of his high-profile status, joined other students demanding change.

“We marched around, arm in arm, and we shut down the Economics building.” That sparked the administration to begin opening the doors to greater Black admissions.. Like other bastions of higher education, the culture at Michigan “was about sports and social change.”

At Michigan, Doughty and his freshmen cohorts were tutored by a graduate student. Helping him untangle the mysteries of calculus, he noted, was Ted Kaczynski, who later emerged as the notorious Unabomber. “He came to our door at the Den of the Mellow Men,” Doughty said, “dressed in camouflage fatigues.” Kaczinski announced to Doughty and his housemates that he was plotting to “blow up a building on campus.”

As he rewound the bizarre account, Doughty fell silent for a second or two as if to absorb the enormity of the announcement shaken with understandable bewilderment.

“But… he was my tutor!” he said softly.

Kaczinski, later embarked on a 20-year rampage of terror, planting bombs that killed three Americans and injured scores of others. He died in prison earlier this year.

Doughty, who earned a degree in education, was part of a contingent of athletes who traveled to Vietnam to get a first-hand look at the ravages of war. Vietnam. “We flew by helicopter over the South China Sea and saw different American bases. One of the bases was attacked while we were there! Seeing the war up close and personal, heightened his sensitivity. The journey “was well worth it.”

During Doughty’s playing days, Memorial Stadium was tagged with a nickname: “The World’s Largest Outdoor Insane Asylum.” During its heyday, when quarterback Bert Jones threw to players like Dougherty and Lydell Mitchell was wowing the 53,000-plus fans in attendance, there was a different pulse in Charm City, said Phil Davis, a Baltimore native.

“The thing to do was to watch or go to a Colts game,” said the retired federal auditor, 77. “Because Baltimore was so Catholic, an arrangement was made for the games to start at 2 p.m. instead of the traditional 1 p.m.” Fans could then attend church and be home in time for kickoff. “You didn’t have to choose between the Colts and religion.”

Davis, a Beltsville resident, said he misses the days when the players took a keen interest in the local community. “It helped the franchise with the goodwill it needs for the city. They would celebrate anything that was good for the team.”

Considering the `hang time’ that Shake & Bake has enjoyed over these decades, it became crystal clear early on that ” Glenn was excited about doing something,” for inner-city families. affirmed David White, s former teammate who personally designed the facility’s sound system and its first disc jockey. “That was his frame of mind.” White, 71, who spent eight years in Baltimore before returning to his native Buffalo, said Doughty is “an extroverted individual, which explains his style and rhythm. After I was released by the Colts, I ended up living in his house for six months. I didn’t have anywhere to go.”

For years, Robert Dashiell has held sway as a high-profile attorney specializing in procurement law. From his front-row seat, Dashiell, 75, is a seasoned observer of the political strategies baked into grassroots gamesmanship. When characterizing Doughty, Dashiell doesn’t hold back when lavishing praise on his indomitable spirit.

“I’ve rarely met anybody so committed and dedicated to a community,” he said of the former athlete-turned-small businessman. “It’s really his adopted community. To his knowledge, Shake and Bake “was the first of its kind in the country.”

Other similarly-themed businesses, he emphasized, feature only roller skating. “But not roller skating, bowling, and fast food all under one roof. The Upton area needed all these things,” adding Shake and Bake is unique because it was the first enterprise since the city’s riot in 1968.

Dashiell, who represented Doughty during his days with the Colts, recalled his client asked to do something special for Upton and West Baltimore. “He came to me and said he wanted to do something for kids. The idea of having it under one roof took off.”

Finding a location, he continued, fell largely in the hands of Lena Boone, a community activist and “Mayor” of Upton. “I introduced Glenn to her. Lena helped with the politics of getting ownership of the land. Glenn lived and breathed it 24/7.”

Armed with a grant from the federal government, the business took shape. It was a good start, but more funding was needed. Enter former mayor William Donald Schaefer. The mercurial mayor, whose legendary tantrums are the stuff of political lore, was “shocked” that the city had applied for the money, announcing he had plans to spend it elsewhere. Eventually, Doughty exchanged the federal loan he had for a “non-recourse loan” “It was a loan he did not have personal responsibility for,” Dashiell said. Ownership of the center was transferred to the city.

Schaefer’s antics knew no bounds. When running for reelection against Billy Murphy, Doughty, who like any astute businessman, welcomed revenue that kept the lights on. When Murphy booked Shake & Bake for a fundraiser, Doughty penciled him in.

The action infuriated Schaefer.

“He didn’t like the fact that (Glenn) rented it to someone who was running against him.” So Schaefer erased the critical support from the city that Doughty relied on in order to keep things humming through the busy summer season. “The city went years and years without trying to renovate it.” Schaefer’s mean-spiritedness and his penchant for retribution was the last straw. Doughty’s wife, Janice, “was so pissed at what Schaefer had done, she said she’d never return to Baltimore. And she never did.”

In 2018, following a $300,000 equipment upgrade, the city reopened the center to community-wide applause. “When I shut it down,” said former mayor Catherine Pugh, “it was as if I had shut down heaven.” The oasis of calm was back on the block.

For Dashiell, working with a larger-than-life personality like Doughty resonates with positive vibes. “The journey we took at Shake & Bake,” he waxed, “opened up worlds for both of us. I will be eternally grateful.”

Doughty tapped Jo Barnes as his first employee and for Barnes it was a life-affirming experience.

“I was the executive secretary when they opened up,” she remembered. “There was a Monday night gospel skate. Churches came out and played more than regular music. We lived right across the street on Pennsylvania Avenue. When they closed at night, my mother and I were their eyes.”

Barnes, 71, who works in the private party suites at CFG Bank Arena, said since the city took over Shake & Bake, something’s missing. “They need to hire the right people,” she stated, to recapture that original magic. “You couldn’t find a more loving couple” than Glenn and wife Janice. “It was almost like a fairy tale.”

Barnes’ son, Christopher Hall, also was intimately familiar with the business. From the time he was a child, he considered the indoor playground a second home and brimming with wholesome competition and interaction.

“I started going to Shake & Bake when I was a four-year-old,” said Hall, 46, a city police detective assigned to Mayor Brandon Scott’s security detail. “Back then, it was a safe- haven from the violence,” highlighted by open-air drug markets.”I had a private skating instructor who came from Pennsylvania three times a week. Uncle Glen set it up.” After school, he would spend time at Shake & Bake, with Doughty’s children, Nikki and Derek.

When the Doughtys moved to Randallstown, Hall explained, he and his mom would be regular guests at the couple’s home, which featured an in-ground swimming pool.. “Uncle Glenn definitely set the bar high as far as expectations. I pray more people follow in his footsteps.”

Growing up in a home with a star athlete as a father meant you were asked to adhere to certain physical rhythms, said Doughty’s daughter, Nikki Doughty, the associate director of strategic initiatives at the Institute for School Partnership at Washington University in St Louis.

As a teenager, “my dad would wake me up at 6 a.m. every morning to walk to the outdoor basketball courts at a school in my neighborhood. Her brother, Derek, would complete the trio. Blurry-eyed, they greeted the day. “First, we had drills. My dad would explain his method of training and why I was doing certain drills at certain times. We did sprints down the court, lunges down the court, lateral switch feet up and down the court.”

But that was merely the warmup, she went on.

“After an hour of all this, we would begin basketball drills.” Through their weekly routine, she underscored the fact that her dad’s personal qualities bubbled to the surface. “He was persistent, patient, motivating, encouraging.”

As a youngster, Doughty demonstrated his unique physicality. Tragically, he also got his first taste of targeted discrimination.”I played running back with the East Detroit Shamrocks,” he recalled. One of his teammates, Ron Banks, achieved fame as a member of the Dramatics, a popular rhythm and blues group from the 70s. “The day the jerseys were to be handed out for all the players that made the team. But Doughty and Banks were singled out. “The parents had to vote to see if me and Ron made the team.” While they got the green light, “that was my slap in the face when it came to racism.”

In time, Doughty relocated to St. Louis to be closer to family. With his sparkling reputation as a compass, he helped create the Takeoff Video Educational Excellence. The company offered multicultural role models that we used in schools. In 1994, the business was renamed Career Information Training Network. Doughty also hosted a sports program on KMOX radio.

Revisiting a life teeming with childlike exuberance and wonder, his voice grows softer, more serious. While naming his heroes—Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Muhammad Ali, and Barack Obama–clearly, he asserted his late father, Otis, tops the list. He was someone whose rock-solid values Doughty will forever aspire to.

In the 1940s, following his military service, his dad “also faced racism,” underscored by an incident in Macon, Georgia. “The police pulled him over, put a gun to his head, used the `N’ word, and said `Don’t come this way again.’ That bitter episode propelled him to move north, where he found work at the post office in Detroit. His climb up the career ladder peaked when he was appointed chief draftsman, where he supervised the design of postal facilities in the Motor City. Meanwhile, his mother, Bessie, ran a summer camp and taught piano. Both of his parents graduated from Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University.

Throughout his life, Doughty said, “he’s just been inundated with music, rhyme, poetry. I always refer back to the legacy of my parents. Think about it. They were able to graduate from a Historically Black college in the 40s. “I was lucky enough to have parents who had loved and put it on all of us. Racism comes at you. You don’t let it defeat you.”

Standing alongside Doughty to witness his engagement to Upton dig deep, rich roots, was a game-changer, Dashiell said. “The journey we took at Shake & Bake,” he waxed, “opened up worlds for both of us. I will be eternally grateful.”

For Doughty, building a business, an unwavering, comforting beacon bathing a rough and tumble world in soft light, is his gift to Baltimore. “It challenged every fiber of your being,” he intoned. “Pure hell and euphoria. That bad boy is still rolling for 42 years now. It was my Super Bowl ring.”