Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum struggles to survive budget cuts

(This is the second story in a three-part series on the Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum.)

The grandstands rumble as more than a dozen Indy cars speed across the scorching pavement of Pratt Street. The yawl of the engines can be heard eastward all the way to Canton; the cheer of the crowd echoes through the canyons of Charles and Howard streets. Vibrations from the roaring racers sound as far south as Federal Hill. But just to the west, on Amity Street, the air is strangely quiet.

For almost two years now, The Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum has been left twisting in the wind; its yearly funding cut from the Baltimore City budget. The city, which lost more than a million dollars on last year’s auto race, is betting on events like the Grand Prix as a way to stimulate commerce and to showcase Charm City, leaving attractions like the Poe House in a cloud of dust. Ironically, a close look at the present situation of the museum and other treasured attractions around town, takes on a Dickensian feel. The city, it seems, is making calculated business decisions in much the same way that economic expedience separated Scrooge from the soul of society.

When the city excised its funding for Edgar Alan Poe House and Museum from its $1.6 billion 2011 budget, the cut set off an unfortunate domino effect. The E.A. Poe Society, which had operated the museum for almost 30 years, and Baltimore’s Commission for Historic and Architectural Preservation (CHAP) were told that the museum had to come up with a plan to be self-sufficient in 18 months. Similar transitions usually take anywhere from three to five years. Still, the die was cast. CHAP engaged a consultant to devise a workable plan while the house remained open; subsisting on a small nest-egg and money raised from special events and charitable contributions.

When the city excised its funding for Edgar Alan Poe House and Museum from its $1.6 billion 2011 budget, the cut set off an unfortunate domino effect. The E.A. Poe Society, which had operated the museum for almost 30 years, and Baltimore’s Commission for Historic and Architectural Preservation (CHAP) were told that the museum had to come up with a plan to be self-sufficient in 18 months. Similar transitions usually take anywhere from three to five years. Still, the die was cast. CHAP engaged a consultant to devise a workable plan while the house remained open; subsisting on a small nest-egg and money raised from special events and charitable contributions.

Many wonder why the city would put the small museum into such a precarious situation. Others worry that the house could some day end up on the auction block.

The Poe House is owned by the Housing Authority of Baltimore and leased to the city for operation. Baltimore made national news last winter when City Hall announced it was considering selling or leasing 15 historic landmarks. These included The Shot Tower (once the tallest structure in America), the War Memorial building, the Civil War Museum on President Street and Orianda House in Leakin Park. Noting that these, and other historic properties are simply sitting dormant, Thomas J. Stosur, the city’s director of planning told The Baltimore Sun, “Just having somebody inside (of these properties) would help the city. Hopefully, we could also earn some revenue off it as well.”

It is hard to say how much revenue the city has earned annually from the Poe House. Attendance figures for the museum were never kept, though Stosur told The Baltimore Post-Examiner that estimates for attendance at the museum and related events run from 3,000 to 5,000 fans a year. At a modest admission price to the museum of only $4, even 5,000 visitors annually might seem like a losing proposition. But studies show there are a number of other benefits in maintaining a vibrant Poe presence in Baltimore, and City Hall is not alone in seeing that windfall.

In the report, Arts & Economic Prosperity IV : The Economic Impact of Nonprofit Arts and Culture Organizations and Their Audiences in The City of Baltimore, Robert L. Lynch, President and CEO of Americans for the Arts, notes that:

“Communities that draw cultural tourists experience an additional boost of economic activity. Tourism industry research has repeatedly demonstrated that arts tourists stay longer and spend more than the average traveler. Thirty-two percent of attendees live outside the county in which the arts even took place, and their event-related spending is more than twice that of their local counterparts (nonlocal: $39.96 vs. local: $17.42). The message is clear: a vibrant arts community not only keeps residents and their discretionary spending close to home, it also attracts visitors who spend money and help local businesses thrive.” The report goes on to add that, “Local businesses that cater to the arts and culture audiences reap the rewards of this economic activity.”

The city’s myopic view of the humanities is only one of the museum’s present problems. Compounding the possible closing of the Poe House are issues with redevelopment in the surrounding neighborhood and infighting between City Hall and CHAP.

The Poppleton neighborhood (where the Poe House and Museum is located) has been experiencing a much needed revival. Entire plots of land have been cleared, and just two blocks south a surging bio-tech park is taking shape. Unfortunately, plans to redevelop some of the Poppleton area have been put on hold.

In July, a federal judge stopped the city from terminating its contract with a New York developer who wanted to revive the Poppleton area. According to a story in The Baltimore Sun, the city alleged that the developer (La Cite Development LLC) had, “…defaulted on its obligations under a six-year-old agreement.” La Cite, countersued, saying, “it was the city’s failure to acquire clear title to all the properties….that prevented financing from being locked down.”

And last month, in what could have been a public relations nightmare, City Hall made a move to oust longtime CHAP Executive Director Kathleen Kotarba. When news of Kotarba’s impending dispatch got out, civic groups, including Baltimore Heritage, rallied to support the embattled commission head. In the end, the powers that be relented. The issue at the heart of the effort to remove Kotarba is her reticence to approve the demolition of the now shuttered Morris Mechanic Theater. But added to the decision to cut funding to the Poe House and the idea to sell or lease 15 historic properties, many wonder if City Hall has a grasp on the myriad benefits of showcasing unique cultural spots or of the intrinsic importance of Baltimore’s beguiling history.

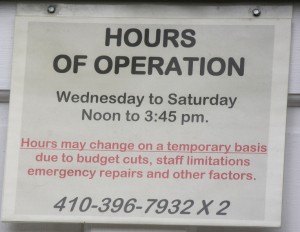

In the meantime, the Poe House and Museum remains open. Jeff Jerome, the longtime curator of the Poe House, continues at that position, though his place in any future plans is unclear. Docent Tony Tendeaus said he hopes that the city will allow this year’s schedule to run its course. That would mean the house would stay open until sometime in November. In addition, the group Poe Forevermore is planning a number of events. A day of observances and programs is slated for Oct. 8. One of the events on the Oct. 8 itinerary is the Poe Society’s annual commemoration at the author’s grave site at Westminster Burial grounds.

The past history of the Poe House is a story of perseverance: from its famous former resident to the dogged determination of those who kept the flame alive. Its present reveals the paradox of a city’s priorities in transition, waving a checkered flag while holding an international attraction in check.

In part 3 of this series, The Baltimore Post-Examiner will look at the future of the Poe House as the City considers coupling the manse to a decidedly different museum.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”

We lose part of our national literary soul if we close the Poe House.