Al Kaline was the Hometown Kid who Got Away

BALTIMORE – On a raw October afternoon in 1991, on the last day they would ever play a baseball game in this city’s old Memorial Stadium, I went looking for Al Kaline and found Doug Hood instead.

Kaline, the Hall of Fame Detroit Tiger outfielder who died the other day, at 85, was working back then as the Tigers’ broadcaster. The Tigers were playing the Orioles on this final, mournful day, and I figured I might find Kaline, the kid originally out of South Baltimore, for a little historical perspective.

But it was Hood who captured the mood of the moment. For many of us in the Baltimore municipal tribe, the closing of the ballpark was a sentimental journey, and a measure of lives, including Kaline’s. We’d all grown older in this place.

In the current season of national isolation and the closing of ballparks everywhere, the memory of Memorial Stadium resonates stronger than ever. Especially now, as Al Kaline departs and we’re reminded, not for the first time, of the power of sports to unite us.

Doug Hood was a stadium usher. He didn’t stroke 3,000 hits the way Kaline did, and he didn’t slug 399 home runs and play a brilliant right field like Kaline.

But he’d known Al when Kaline was a three-sport star at the old Southern High. When school let out, Al played every summer for a bunch of amateur teams all over the city, including the club sponsored by Gordon’s Stores.

“I was Al’s batboy,” Hood said proudly. “He played left field for Gordon’s Stores. I saw him throw out a guy at home plate on the Number 3 diamond at Herring Run Park.”

“Pretty good throw?” somebody said.

“You kidding?” Hood said. “Al was on the Number 2 diamond when he threw it.”

There you go. Detroit thinks they know Al Kaline, he was saying. Not like we knew him around Baltimore, pal. We knew him before anybody did. We knew him as one of our own.

He hadn’t spoken to Kaline in years. But now, standing just outside the baseball press box, Hood said to a security officer, “Al’s not available? Well, if you see him, tell him his old batboy said hello. And tell him how proud he made us every time we saw him play here.”

The conversation comes back now, like a haunting, with Kaline’s death. In a time when no one on the planet plays organized sports because of this killer coronavirus, his passing takes us back to a time recalled more fondly than ever.

For those of us who grew up here when Kaline was establishing himself as a major leaguer, he represented a special kind of longing. In 1953, he jumped to the Tigers as a bonus baby, right out of Southern High. He never spent a day in the minors.

In the next two years, some special things happened. In 1955, Kaline led the American League in batting average. He was the youngest player ever to do that. He was 20. He was barely older than the kids in every neighborhood around here who had dreams of becoming the next Kaline.

He’d broken in as a regular in 1954, the year the Orioles returned to major league baseball after half a century’s absence. And every kid in town knew that Kaline was a hometown guy – we heard Chuck Thompson or Ernie Harwell say it on the radio any time the O’s played the Tigers.

Kids still talked a lot about baseball in those days. There were little leagues everywhere. Every drug store had stacks of baseball cards for sale (and included bubble gum hard enough to break teeth). Every day the newspapers carried batting averages and home run totals, which we analyzed like stock market tables. There was Kaline, hitting .340.

And some nights you’d lie in bed listening to the Orioles on the radio, and Kaline was punishing some O’s pitcher, and you’d think, Gee, if the Orioles had only gotten a franchise one year earlier, maybe they could have signed him and kept him right here.

He was the hometown kid who got away. He came out of the Westport area of South Baltimore, on a scruffy working-class street that produced some pretty tough kids over the years.

But his folks instilled some solid values. Over 22 seasons in the major leagues, Kaline was a figure of class and dignity and respect. Doug Hood had it right. Al Kaline made us proud, every time we saw him play.

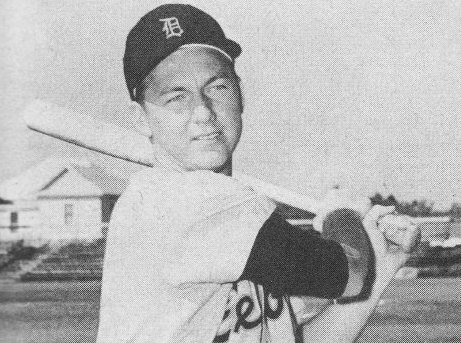

Feature photo: Major League Baseball Hall of Fame player Al Kaline in his official 1957 Detroit Tigers photo

Michael Olesker, columnist for the News American, Baltimore Sun, and Baltimore Examiner has spent a quarter of a century writing about the city he loves.He is the author of several books, including Michael Olesker’s Baltimore: If You Live Here, You’re Home, Journeys to the Heart of Baltimore, and The Colts’ Baltimore: A City and Its Love Affair in the 1950s, all published by Johns Hopkins Press.