Rethinking Possible: A Memoir of Resilience

The Baltimore Post-Examiner is proud to present an excerpt from Rethinking Possible: A Memoir of Resilience by Baltimore author Rebecca Faye Smith Galli. The book is available at Amazon.

Galli is a weekly columnist who lives in Baltimore, Maryland and writes about love, loss, and healing. Surviving significant losses―her seventeen-year-old brother’s death; her son’s degenerative disease and subsequent death; her daughter’s autism; her divorce; and nine days later, her paralysis from transverse myelitis, a rare spinal cord inflammation that began as the flu―has fostered an unexpected but prolific writing career.

Summary: Becky Galli was born into a family that valued the power of having a plan. With a pastor father and a stay-at-home mother, her 1960s southern upbringing was bucolic―even enviable. But when her brother, only seventeen, died in a waterskiing accident, the slow unraveling of her perfect family began.

Though grief overwhelmed the family, twenty-year-old Galli forged onward with her life plans―marriage, career, and raising a family of her own―one she hoped would be as idyllic as the family she once knew.

Though grief overwhelmed the family, twenty-year-old Galli forged onward with her life plans―marriage, career, and raising a family of her own―one she hoped would be as idyllic as the family she once knew.

But life had less than ideal plans in store. There was her son’s degenerative, undiagnosed disease and subsequent death; followed by her daughter’s autism diagnosis; her separation; and then, nine days after the divorce was final, the onset of the transverse myelitis that would leave Galli paralyzed from the waist down.

Despite such unspeakable tragedy, Galli maintained her belief in family, in faith, in loving unconditionally, and in learning to not only accept, but also embrace a life that had veered down a path far different from the one she had envisioned. At once heartbreaking and inspiring, Rethinking Possible is a story about the power of love over loss and the choices we all make that shape our lives ―especially when forced to confront the unimaginable.

Prologue

What’s Planned Is Possible

All the love we come to know in life springs from the love we knew as children.

—Unknown

WE WERE FIVE, until we weren’t. Our world was orderly and predictable, until it wasn’t. We knew so much about love, laughter, and the joy of being family, until we didn’t. I remember one Friday night meal so well. Especially my prayer, the one that still haunts me.

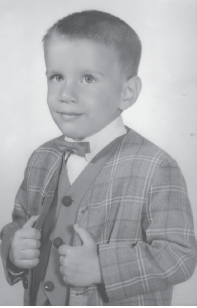

It was summertime and we’d been preparing for weeks. In 1964, I was six years old and I thought I knew everything. I was the rule-follower and vigilant enforcer, “in charge” (or so I thought) of my four-year-old brother, Forest, and my baby sister, Rachel, who was three.

After each trip to the grocery store, we would watch Mom set aside one or two items for the “beach box,” a sturdy cardboard box she tucked beside the refrigerator, far out of our reach. Saltines, Peter Pan peanut butter, Mt. Olive dill pickles, and two boxes of Life cereal filled the front, while the special treats, Lance cheese crackers and Little Debbie oatmeal pies, were mostly hidden near the back.

Our plan was to head out before daybreak the next morning for our annual two-week trip to Myrtle Beach. My siblings and I colored as we waited in the den for Dad to get home. It was almost time for dinner, a family staple you could set your watch by. Six o’clock was the usual magic hour when all outside distractions were turned off, put up, or otherwise silenced so we could share an uninterrupted family meal together. We knew no other way to dine.

That night was a special dinner, a “clean out the refrigerator” breakfast-for-dinner meal—eggs, bacon, grits, and gravy. I watched Mom’s shadow dart back and forth between the stove, refrigerator, and sink. Then I heard a pop. “Canned biscuits tonight, guys,” I whispered. “Don’t say anything, Ray.” I shot a look at my sister, her blonde pigtails swinging back and forth with each stroke of her crayon as she hummed, “Oh My Darling, Clementine.” She stopped coloring and returned my look, a slight smile curling at one side of her mouth.

“She won’t.” Forest interrupted our standoff and moved in front of our sassy sister to see if he could get those mischievous green eyes to lock onto his soft blue ones. “Will you, Ray?”

“But homemade biscuits are better.” She peered beyond Forest to rest her impish eyes on me. “And I don’t like canned biscuits.” And the battle of the sisters, another family staple began.

“Yes, you do,” I said.

“No, I don’t.”

“Yes, you do, Ray. You eat them all the time.”

“No, I don’t!” She pounded her fist on the coloring book. “Homemade biscuits are better and you know it, Becky,” she fired back, far too loudly as she jutted out her chin and crossed her arms, jamming her fists into her armpits, her posture of defiance I knew too well.

“Shh,” I hissed. “Mom’s going to hear you.”

True to our Southern roots, canned biscuits were the exception in our household. But this fight wasn’t about biscuits.

“Your mom makes a mean biscuit,” Dad said each night when a fresh hot homemade batch was passed around the table. Canned biscuits were a rarity. But if served, we were never supposed to mention it. “Mom works hard to get that dinner on the table. Let’s be grateful, not critical,” Dad would remind us. Apparently, Rachel hadn’t learned that lesson, so of course I had to set her straight. She could hurt Mom’s feelings if she complained. Maybe even ruin dinner.

“Everything alright in there?” Mom’s voice cut through our bickering. It wasn’t her “chocolate voice,” the one that was anything but sweet—that rich dark growl let us know we were in trouble for sure. This time it was only her warning voice, louder than normal to drown out the iron skillet’s sizzle, but still sharp and melodic with the last syllable emphasized for attention-getting effect.

“No unpleasantness,” she crooned, her shadow darting faster. “You kids know better. Your father will be home soon.”

“See,” I whispered, jutting out my chin in my own defiant posture. Dad called Rachel“little bit” because she was the youngest and small for her age, but there was nothing little about her ability to stir things up; we could count on her for that.

“Remember, Ray, we are going to the beach tomorrow, the beach!” Forest gave hershoulder a gentle squeeze, and then widened his eyes. “So we should eat what we have. They may not be the best, but they’re still good, right?” Ever the peacemaker, Forest had presented his case.

Rachel looked down at her scribbling and studied it. “Well, okay,” she sighed, unfolding her arms so she could start coloring again.

Forest smiled at me and I grinned back in approval. “Hey Ray, you smell that bacon?” I said, trying to lighten the mood and unify the troops. We love bacon, don’t we?” Forest and I both nodded encouragement to her.

“Yes, we do!” she replied and finally smiled, beginning to hum again.

We’d done it. Forest had helped her focus on the good while I reminded her of what we all loved and could look forward to. Together, we’d had ganged up on our sister to get her to behave, a dynamic we would continue—until we were no longer three and we couldn’t.

“Dinner!” Mom called, motioning us in as she primped her hair and pulled her bright red lipstick from her apron pocket. “Your father’s coming up the back steps.” She touched up her lips and quickly blotted them with a tissue, stashing both back into the pocket before running her tongue across her front teeth and checking her smile in a knife blade’s reflection. Then she looked at the three of us, searching our faces. “Is everyone happy?”

“Yes, Mom,” we said in unison. That’s what mattered. Happiness was a premium

commodity in our household, right up there with family time, gratitude, and planning. And Mom was the master of happy—she looked it, lived it, believed in it, and faithfully promoted it. But happiness took work. We each had to do our part whether preparing the dinner table or settling our differences. I shot Rachel another look, trying to raise one eyebrow like Mom did when she meant business. Then Dad burst through the back door into the kitchen and announced, “I’m home!”

“Dad-deeee!” we squealed and jumped on his neck, his Old Spice aftershave lingering despite the end-of-day stubble. His jet-black hair hadn’t moved—slicked back into place with that little dab of Brylcreem. He kissed Mom hello while we still clung to his neck.

Old Spice and Brylcreem—the smells of the sixties, of safety, of my larger-than-life

father, the anchor of our family. At six foot three, my lanky blue-eyed minister father towered over all of us in both presence and charisma. He had a flair for the dramatic—both at home and at work from the pulpit—well, actually anywhere he went. With little effort, he commanded the room with his booming voice, broad smile, and eyes that seemed to look into your very soul.

“Are we ready for dinn-nahh?” he asked, his deep refined tone playfully mocking thehodgepodge menu—even though it was a family tradition. Any meal can be a special family time with the right attitude and Dad always knew exactly how to spin it to make is special. We each took our place at the table, immediately holding hands. Thank goodness the biscuits were beside Dad and the bacon was beside Rachel.

“Becky, I believe it’s your turn to pray,” my father said, nodding and shooting me a quick look, one of his signature pulpit moves he used to direct the service. Mom concurred with her approving smile and matching nod. No one could take a bite before we said amen. It was important to be thankful, even for canned biscuits.

I started my standard, “God is great, God is good . . .” But just before my “amen” and our customary hand squeeze, I took a short breath and added, “And please, God, let nobody die during the next two weeks.”

“Becky!” my parents exclaimed, both forgetting the hand squeeze. Rachel’s and Forest’seyes popped open, their jaws dropping in shock, so surprised they were that I’d apparently done something wrong.

“Well, isn’t that a good prayer?” I asked, raising my voice a little higher and thinner,hoping for an angelic tone. “I just want folks to stay real healthy for the next two weeks. If someone dies, it’ll ruin our vacation. Dad will have to come back to do the funeral.”

Although I don’t recall the exact response, I’m sure I received a lengthy lecture on the purpose of prayer. Even so, I thought I’d hit the right mix: I’d blessed the food and let God know what was on my mind—just in case he forgot. Regardless, I still hated funerals. They messed up my plans.

Funerals were the kind of thing I worried about as a PK—a nickname for preacher’s kid that I didn’t like much but accepted. PK’s, like doctors’ kids, have to deal with being on call, emergencies, and the reality that other people’s problems become our own in a split second.

Although I grew up in a household of faith, where flexibility was a requirement, I didn’t like the three D’s—death, divorce, and disease—intruding on our family plans. These life-changing events were just a side effect of my father’s job, a routine yet necessary nuisance.

I cringe now at the thought of that foreboding conversation, the selfishness, the shallowness, the way I discounted others’ tragedies. But then I remember that I was only six years old. And it was a gutsy prayer. At least I was honest.

Later that evening, all five of us gathered for the pre-packing meeting. Dad rattled off each item on the checklist and the kids took turns hollering, “Check!” as mom looked on.

“Great job, guys!” Dad said, kneeling down to give us each a hug. “Faye, I believe your children have their ducks in a row.”

“We do, Daddy,” I said and turned to my siblings. “What do we say, guys? What doesDaddy always say?”

“What’s planned is possible!” we said, just as we had rehearsed. And we knew this plan by heart.

We knew next would come packing time, Dad’s artful but systematic way of stuffingevery nook and cranny of the large trunk of the Ford LTD. “Lay it all out,” he would soon instruct so he could size up the load. “Luggage here. Beach chairs and sand toys there. Books over here.” And we would litter the driveway with our memories-in-waiting.

We knew the alarm would be set for 5 a.m. the next morning, but that Rachel would already be up by then. We knew she would wake Forest and me—like she did every morning, but this time we wouldn’t mind since the earlier we left, the sooner we would get there.

We knew Dad’s “study time” would fill every morning while we played on the beach with Mom. We knew around noon we’d meet Dad back at the house for lunch. We knew he’d come down to the beach for twenty minutes about midafternoon. “I don’t really like the beach,” we knew he’d say when we begged him to stay longer. “It doesn’t like me,” he’d say since he burned so easily. “But I love it because you love it.” Then he’d kiss us each on top of our heads and go back to the house.

We knew Mom would cook every night except for Thursday when we would go to Calabash for seafood. We knew we’d have to come in early from the beach that day to avoid the “gosh-darn beach traffic” and “the cotton-pickin’ long lines” outside the restaurants—although that was precisely how we judged the “good ones.” We knew we each would have a vote in what restaurant we finally selected, although Dad could be mighty persuasive if one struck his fancy or he had the “inside scoop” from one of his friends. We knew we would be seated in whatever restaurant we picked no later than 5 p.m. After all, that was the plan.

We knew Mom would get the flounder and Dad would get the two-choice combo platter, “shrimp and oysters, please.” We knew Forest and I would get just shrimp, no slaw, but with extra hush puppies. And we knew Rachel would get a cheeseburger, plain, no mayo, mustard, or pickles since the juice ruined the taste of the cheese. But before we would even get in line, we would have checked the menu posted in the window to make sure they served cheeseburgers, since, well it was a seafood restaurant.

We knew Forest would order ice tea without ice. We knew the confused waitress would say, “Excuse me, sir. Did your son say ice tea with no ice?” We knew Dad would explain that Forest thought that ice diluted the flavor of the tea. Then Dad would joke that Forest must have ancestors from London, “Who else do you know orders ice tea without ice?” Then he’d rub the top of Forest’s shoulders and tell him, “That’s alright, son, the Brits are a fine lot,” and pull him closer to say, “It’s okay to march to the beat of a different drummer.”

We knew if Rachel were in a precocious mood, she’d complain, “Why does he order tea that way? It takes too long!” Then add, cutting her eyes at me, “That’s stupid.” Then I would tell her that she was the one with the stupid order. Who gets a cheeseburger at seafood restaurant anyway? (Even though secretly that burger looked pretty good, especially since I really didn’t like shrimp; I only ordered it to please Dad—and be like Forest.)

And then Dad would say, “Now girls,” with his deep stern voice and I knew that she’d done it again—got me in trouble when she’s the one who’d erred. Then Mom would lift one brow and say softly in her public scolding voice that we had been unkind to one another, un-ladylike, and “plain.” And we would get up right then, in the middle of restaurant, to apologize and hug one another as instructed.

But squabble or not, we knew when the order of iceless tea came, Dad would ponder the tea bag and its life of extremes—how we boil it to get it hot, and then ice it to cool it down. How we make it sweet with sugar, and then make it sour with lemon. Forest and I would listen intently—even though we heard the story each time we went out to a restaurant. And Rachel, predictably, would roll her eyes.

But before the food came, we knew Forest would beg at least once, “Dad, tell one of your jokes.” Dad had so many we thought he should number them so we would only have to call out the number. But instead, he’d give us a few options and then usually tell them all. We’d all laugh hard and long, but we knew Forest and Mom would laugh until they couldn’t breathe and sometimes cry. Most of all, we knew we would have a great time, a highly anticipated expectation we exceeded every summer for fourteen years.

Until we couldn’t.

“What’s planned is possible,” my father taught us at an early age.

“Got to get my ducks in a row,” Mom said at least daily as she showed us how to plan your work and work your plan. Set goals, focus, and achieve them, I learned. Our family, individually so different, was united by lessons and traditions that were meant to last a lifetime.

But sometimes, the best-laid plans simply aren’t possible.

Chapter 1

The Accident

We are shaped and fashioned by what we love.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

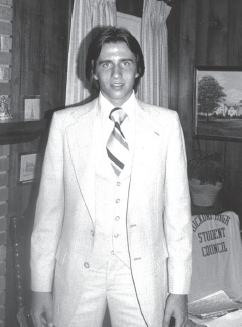

FOURTEEN YEARS LATER, Sunday September 3, 1978.

The grill was still hot, smoking after the third batch of burgers for our Labor Day celebration. The smell of freshly baked brownies had lured some of us inside. I knew some of the kids, but had been invited by a friend of a friend to an off-campus apartment I’d never visited before. I was twenty years old and had just begun my junior year at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I was looking forward to that sweet-spot year, comfortable with college expectations without the senior year pressures of figuring out what’s next.

The phone rang, interrupting the banter of our casual reunion.

“Hey, Becky,” my friend hollered from the back of the kitchen. “It’s your dad.”

“That’s weird,” I mumbled as I excused myself from the group, leaving a lone brownie perched on the side of my paper plate. “I wonder how he found me.” I was at an obscure off-campus apartment. It was 1978, so there was no call-forwarding, custom greetings, or leaving messages. An uneasy tightness started twisting my stomach before I even said hello.

“Dad?”

“BB,” Dad began, using his pet name for me, “There’s been an accident,” he said and then swallowed hard. “Your brother’s been hurt.”

“What?” I whispered, sucking in air and information as my knees bent and I slumped to the floor.

“He was waterskiing on Lake Hickory and hit the edge of the pier,” Dad continued in a steady tone. “He hit his head . . . we are moving him to Winston-Salem . . . he’s unconscious.” His voice trailed on with information that I heard but could not process. The words stalled outside my ears, unable to break through the disbelief. Forest. An accident. Waterskiing. Hit his head. Unconscious. Going to another hospital in Winston-Salem, an hour and a half away.

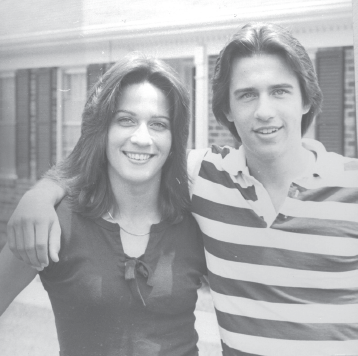

“But he’s going to be okay, right Dad? He’s going to be okay?” I stammered back to my father. Forest had just come to visit. I just gave him a haircut. I just borrowed his leather-trimmed jeans. We wore the same size.

“He’s stable, BB, but this is serious.” Stable, but not okay. Coded words. Dad was so solemn. Usually he was optimistic, hopeful. He could find the good in any situation. But this time I could not get one positive word out of my father.

More words and questions pulsed across the wire. We pieced together a plan. I called my boyfriend and he agreed to drive me from Chapel Hill to the hospital in Winston-Salem. Mom, Dad, and Rachel would meet us there. I drove back to my apartment, threw a few clothes in a bag, and waited on the steps for his arrival. I’d never heard Dad’s voice be so grim, so unwavering, so haunting. I squirmed on the brick step and traced my finger along its edge, letting its rough but firm pattern attempt to stabilize my spinning mind. But it was no use. All I could think about was my precious family.

***

WE WERE MORE than a family of five—we were five RFS’s, we were proud to point out:

Robert Forest Smith Jr. (RF)

Ruby Faye Smith (Faye)

Rebecca Faye Smith (Becky)

Robert Forest Smith, III (Forest)

Rachel Fern Smith (Rachel)

Dad would kid us that it took him quite a while to find a woman with just the right initials. After two years of marriage and a miscarriage, I was born. Two and a half years later, Forest was born, with Rachel joining us only seventeen months later. At one point, Mom had three kids under the age of four. We had a busy, active household.

As a family, we shared more than our initials. Sit-down breakfasts and six o’clockSouthern suppers punctuated our daily routine. Mealtime conversations focused on our schedules, school happenings, current events, and opinion swapping about everything from the latest movies to the current congressional race.

My siblings and I were well-schooled in all aspects of family life, void of the typical gender limitations assumed at that time. Rachel and I knew how to wash a car, mow the lawn, and check the oil in our cars. We could spiral a football, sink a free throw, and hit at least a double on the softball field. I wasn’t much of an athlete, but I was still a competitor. In another dinnertime blessing, I prayed for my team to beat Rachel’s in basketball.

Again, Dad tried to help me with that “purpose of prayer” conversation.

“BB, you should have prayed for the best team to win.”

“But Rachel has the best team,” I said matter-of-factly. “And I want to win!”

Forest, a three-sport athlete with exemplary sportsmanship, knew how to fry a pork chop, set the table, and thread a needle. We all knew how to make “hospital corners” with our bed linens, clean a toilet, and jumpstart a car battery.

My father’s grandfather, Papa Benfield, was a minister, as was my father’s Uncle Knolan. When Dad “felt the call” to the ministry, both men gave Dad the same advice: “Make sure and spend time with your family. The needs of the pastorate can be all-consuming.” They were right about that, as my childhood prayer attested.

Dad took their advice. As soon as they were married, my parents decided that sundown Friday to sundown Saturday would be reserved for the family. Once they had children, Friday night was date night and Saturday was reserved for the family—picnics, sports, cookouts, and special outings with each child. I loved spending time with my family. My parents were bright, funny, and always in motion, learning and teaching. When I turned thirteen, when all my other friends were complaining about their parents, I remember secretly wondering what I was supposed to rebel against.

Our family was close by design.

***

MY STOMACH STILL churned as I tried to reconcile Dad’s strange voice with what lay ahead. I glanced at my watch and decided to go back into my apartment to grab a few packs of Lance cheese crackers and a couple of Cokes, staples I always had on hand. I sat back down on the step, opened a pack, and took a bite. It was an odd but reliable comfort food, helping me get through more than one all-nighter—and a few hangovers. That familiar crunch and nutty taste reminded me of those Saturdays long ago when Dad would take me to the Esso filling station where his buddy, Rex, would fill up our car with the weekly allowance for gas. Dad would buy a pack of Lance and a Coke for me for a quarter. It seemed so extravagant at the time. I would munch on my crackers and sip on my Coke, enjoying the salty sweetness, while I listened to Dad “shoot the breeze” with Rex. Dad would ask him about his service station business, his family, and then tell him a few jokes.

Dad could talk to anyone about anything, it seemed. Whether in the pulpit, at a gas station, or hanging out in my college dorm room, he peppered his conversations with timeless stories as well as knee-slapping jokes. My friends loved him. “Glad you got to see me, girls!” he would boom to my college buddies before he heel-clicked and saluted good-bye, leaving them perplexed. He nicknamed everyone, often to help him remember names, which was so important for a minister. “How are you today, Miss Sarah-with-an-h?” he would ask. “How’s it going, June bug?” he’d quip. “Good morning, Pa-trish-aa!” he would announce, as if he were at a horse race and she were the winner. And to really throw them off balance, he’d ask, “How are you prognosticating?” with the face of a straight man waiting for a punch-line response, which again, was usually another puzzled look.

“Your dad is a hoot, the funniest minister I’ve ever met,” my friends would tell me.

Occasionally someone would try to cash in on Dad’s heavenly “connections,” and ask, “Can you help us out with the man upstairs and arrange for some good weather for tomorrow’s football game?”

“Sorry,” he’d reply without blinking, “I’m in sales, not management.”

I thought about that role as I took one last bite of my cracker while my boyfriend pulled up. I threw my bag in the backseat, jumped in the car, buckling up my seat belt.

And then I wished with all my heart, that Dad was in management.

***

MY BOYFRIEND, CARTER, lost himself in his “tunes,” as he liked to call them, singing along to “Hotel California.” Our bumpy two-year relationship was at a good place, for the moment.

Carter was a scholarship athlete, one of the captains for UNC’s wrestling team. We’d met our freshman year. When I told him about Forest’s accident, he borrowed a friend’s car to drive me to the hospital.

I don’t remember talking, only thinking. Detailed thoughts. Distracting thoughts

Untouched by hardship, neither one of us had much to offer one another. At age twenty, how could you possibly know what to say to help? We were in foreign territory, so I let the radio’s blare fill in the chasm for the ninety-minute trip to the hospital.

The sharp edge of Dad’s voice still rattled me. Then I thought about Mom, his perfect companion. I’m sure she was right by his side, as usual. I cut my eyes to glance at Carter. Perfect companion? Not so sure. I wondered if Mom and Dad had any bumps in their college days. Maybe we only heard the storybook version. Mom, Ruby Faye, was the oldest of four, her other siblings similarly named: John Ray, Robert Clay, and Pearl May. Her mother called the girls, Ruby and Pearl, her little “jewels.” Mom’s father died leaving his wife with four children ages eight, seven, six, and five. Because of the “financial situation,” as Mom used to explain, the children moved to an orphanage in Kinston where Mom stayed until she received a scholarship to attend Wake Forest University—in Winston-Salem. There, she met my father.

I flipped the visor down and adjusted my sunglasses. The glare of the open road hurt my eyes—and my heart. Winston-Salem. Mom and Dad met there. I was supposed to go to school there. And now Forest is in the hospital there. The city that held so many memories, so much promise, now terrified me.

***

I LET THE shaded warmth of the sun slip my mind into more reflections about my family. My childhood seemed distant, yet present every day. What made us so close? Although love and laughter ruled in our home, expectations were high. We were the first family of the church, with five pastorates that had ranged in size from five hundred to two thousand. I couldn’t remember a time when I didn’t feel like we lived it a glass bowl. It wasn’t uncomfortable—just a fact of life. We were often tutored on what to say, when to say it, and exactly how to say it, from how to answer the phone to what kind of information to give out about our family.

As for discipline, Dad was the tough parent, in charge at all times. He would “give us to the count of three” to “straighten up and fly right,” or else. He rarely got to three.

Mom was less stringent, but focused on kindness and manners. “Pretty is as pretty does,” she’d say. “If you can’t say something nice, then don’t say it at all.” In fact, there were limits on the words we were allowed to use. We did not lie. We “told stories.” Nothing was ever stolen. It was “misplaced.” Mom even had trouble with the word, stink. Things did not stink. They “smelled badly.”

Yet they were a team. Saturday nights were a prelude for the Sunday service. Mompainted nails and pin-curled hair. She made sure each child had picked out a complete Sunday outfit—lacy socks an d gloves for the girls, a bow tie and vest for Forest.

Even in our teens, we spent Saturday evenings together as a family. All five of us would hang out, playing basketball in the backyard or washing our cars. Dad would grill steaks, while Mom made salad, baked potatoes, and Forest’s favorite dessert, a cherry cream-cheese pie with a homemade graham-cracker crust. We often ate in the dining room using the good china and cloth napkins so we could practice our table manners. Then Dad would retire to the study for one final rehearsal of the sermon he would deliver the next day.

Then I remembered it was Sunday. Had they had that meal last night? What if it was—what if? The unknown was scrambling my thinking, jumbling the past and the future with the present that made no sense. Forest had to be okay. Had to be! And I took off my sunglasses and buried my wet eyes into my hands.

***

WINSTON-SALEM, TWENTY-five miles, the sign read when I finally looked up. I slipped my sandals off, tucked my feet under me, and shut my eyes to block out the haunting what-if’s for just a little longer and focus on Forest, on what I knew. I must stay positive.

Winston-Salem was the home of the Wake Forest Demon Deacons. Hadn’t Forest just finished his application for early admission? I knew he was working on the essay. He would be a shoo-in, no question. Student Council President. Youth Council leadership at church. Sports. Mission work. Music. Hadn’t he just been elected president of a regional council, too?

Leadership came so naturally for him. Others seemed to be drawn to him for guidance, like Dad. Yet, like Mom, he was a sensitive soul. Patience and understanding permeated all of his relationships. He even managed to puzzle Dad a couple of times, I smiled. That’s hard to do.

“Sometimes you got to ‘get mean,’ son.” Dad would say after a loss in a football or basketball game.

And I’d watch Forest listen, but then discount the advice. “You don’t have to be mean to win, Dad,” I can hear him saying.

In elementary school, Forest was bullied one time and came home to tell the family. Dad thought it was the perfect time to educate him about the “fight or flight” response and encouraged him to stand up for himself and fight.

“But Dad,” Forest said, “There is another option. I can make him my friend.” I marveled at my younger brother and his offbeat but on-target insight. He never felt like my “little” brother in that stereotypical annoying way. There was nothing little about him—his thoughts, plans, laughter, or presence. In fact, I don’t think I ever called him my little brother, just, my brother. Sandwiched between two sisters, Forest liked his unique role, often signing his notes to Mom or Dad, “Your only begotten son.”

He was preparing to do what I had wanted to—attend WFU, like Mom and Dad. Those were my plans, too. Until that letter came.

***

I THOUGHT I’D blown it. That final interview was terrible. I’d told the scholarship selection panel about my high school accomplishments, my well-rehearsed future plans, and then skated through all the sensitive political questions about Watergate, the pardon, and the stumbling Gerald Ford, having pored over the latest issues of Newsweek, BusinessWeek, and Time. One stately gentleman whose three-piece suit was garnished with initialed cufflinks and a Carolina-blue striped tie asked me something about the aid programs for the OPEC countries. I had no answer. I remember staring at his gold cufflinks and thinking it was over.

“I don’t know,” I’d said. Like Forest, I was never very good at BS. One lady lookeddown at her notes and scribbled furiously. The three-piece suit guy cleared his throat and shifted in his seat. “I’m sorry,” was all I could think of to say. “But I have to be honest. I really don’t know.” And I held the tears until I got back home.

It’s not your first choice anyway, I kept telling myself. I’d only applied to UNC because I’d been nominated for a Morehead (now Morehead-Cain) scholarship. We were Demon Deacon fans to the core, especially when pulling against the always nationally ranked UNC Tar Heels during basketball season. Ugh, could I really go there? Mom and Dad met at WFU. Dad had served on their board of trustees. We even named our German shepherd “Deacon.”

“What’s in this envelope could change your life,” Dad said, waving it high above his head. And it did. The letter offered a four-year scholarship included tuition, books, paid internships, and a stipend. It was a lot to consider, especially given Dad’s minister salary. I was the first of three who would need college tuition. I accepted. But Dad always enjoyed telling folks, “Yes, she chose UNC, but they had to pay her to go there!”

That was the Dad I knew. Finding just the right spin, even in disappointment. Please, oh please, let Dad be the Dad I knew and find something positive to say.

***

CARTER’S VOICE SNAPPED me out of my thoughts. He was singing again, Fleetwood Mac this time. “Don’t stop, thinking about tomorrow, don’t stop, it’ll soon be here, it’ll be, better than before, yesterday’s gone, yesterday’s gone. Don’t you look back . . .” But somehow that’s all I could do. I kept replaying Dad’s words. When I thought about it, he didn’t mention Rachel when he called. That was odd. She and Forest usually skied together. They had become close after I left for college. I didn’t miss the squabbles and drama, but I envied the way they tag-teamed high school. They worked at the same dry cleaners, had the same friends, and both loved to water-ski.

I wonder if she was with Forest when he hit the pier. Oh my, I wonder if . . . if . . . if she saw it! I sat up straight, wide-eyed as a cold shudder froze my spine. I shook my head hard, trying to erase that horrific thought. I couldn’t bear it.

***

WE PASSED THE exit for Wake Forest campus as we approached the hospital. Keep thinking of the future, the plans, I reminded myself. Forest would go there, I was sure of it. He’d earned it. Like Dad, he was unafraid to be front and center, and comfortable in the spotlight. Although I teased him about wearing his three-piece Sunday best to run his Student Council meetings, I secretly admired his guts. Even though I could handle the spotlight, I preferred a behind-the-scenes brand of leadership—networking, negotiating, problem-solving to gain consensus. Forest, on the other hand, came alive onstage.

His dreams were huge, far larger than mine. Although we both had plans to pursue a law degree, Forest carried a United States Senate Seal on his key ring, vowing that one day he would be there and give the same seal to his supporters as a senator had given to him. Wake Forest was his next step; Winston-Salem his next stop.

But not like this.

We arrived at the hospital. Carter parked the car while I rushed in to find my family in the intensive care waiting area. Rachel was balled up at the end of a faded green couch, her knees tucked into her chest, her arms crossed, fists up into her armpits. There was no defiance this time—she rocked herself softy, with no words. She glanced at me and then returned her stare to the floor.

Mom sat at the other end of the couch, perched on its edge with her shoulders slumped, hands clasped, and head bowed. She looked as if she were in a deep prayer as her lips were moving but no sound was made.

Dad was pacing, his hands shoved deep into his pockets as his wingtips tapped softly on the polished floor. He heard me and spun around to greet me. “BB, honey,” was all he said before he hugged me tight. I could feel him swallow hard as he held me. No words from him—again. When he finally released me, I looked up into a face that matched the unknown voice I’d heard on the phone only hours earlier. Mom and Rachel moved awkwardly to join us, lumbering as if they were sleepwalking.

Mom’s face was pale, her bright red lipstick now a faint shade of crimson. Rachel barely looked up before we all hugged, but I could tell she was clutching something in one hand. We held each other for a while and then settled around a table in a nearby waiting room.

“What happened?” I said.

“It’s my fault,” Rachel said, her voice low and robotic. “I should have been there withhim. He said just one more round. That Dad said it was okay. He told me he would meet me back at the house and threw me his wallet.” She unclutched her hand to release the smooth brown wallet that thudded onto the center of the table. We all stared at it as if it held the key to Forest’s life, his next planned moment.

“No, no, honey,” Dad said as he got up to hug her. “This is not your fault, not at all. Itwas an accident, honey. An accident.” Forest had called home earlier in the afternoon to ask Dad if he could stay out a bit longer. They had planned to hit some golf balls, but Dad relented, letting his nearly eighteen-year-old son have a little more time in the sun with his friend. Rachel, then sixteen, was with them for a while, but had left before his last run in the cove. Apparently he was waving to some friends on the shore and skied too close to the pier, hitting it with his leg and head. He landed face down in the water.

Forest’s friend and some bystanders helped pull him from the water and onto the pier where he tried to stand up and speak, but then collapsed. The rescue squad rushed him to the local hospital where he was first examined, then transferred to North Carolina Baptist Hospital and Wake Forest’s Bowman Gray’s School of Medicine, some seventy miles away from Hickory.

We sat in the small room, with small talk, and small Styrofoam cups of terrible coffee, each of us praying for Forest to wake up. For Forest to be okay. For Forest to be Forest and come through this. Somewhere in all the hubbub, Carter came in, comforted us as well as he could and then left. He had to return his friend’s car and get back to school for practice. Our numbed family of four settled into the rhythm of receiving reports from doctors and saying prayers with ministers and friends. We greeted each with a hopeful smile. But the reports weren’t good. Forest was not improving.

Although I wanted to see my brother, at the same time, I didn’t. Maybe if I didn’t see him, the accident wouldn’t be real. I hovered outside his door and finally I slipped into his room, staring at the floor’s cream tiles, flecked with shades of gray. I exhaled, dabbed my eyes and then raised them slowly to look at my brother.

He was quietly sleeping it seemed, his long lean body resting comfortably on his hospital bed.

Except for the tubes. And the pumps. And the beeping.

I moved closer, trying to reconcile what I saw and what I knew. Though Forest and I were almost three years apart; we could pass for twins. We shared brown hair, blue eyes, and a matching long-legged build. I touched his brown hair, the exact same shade as mine. I’d just cut it. The trimmings went everywhere. I’d never cut anyone’s hair before. “Not too short,” he said gently. “You can do it, Beck.”

I wanted him to open his eyes, to see my eyes in his. I tried to talk to him. About his hair. About our plans for me to visit him at WFU. “Hey, Buddy, you got to get better here.” I took his hand in mine. When we were kids, Dad would take our hands and entwine our fingers, covering our wrists. Then he’d ask Mom or Rachel to pick out which fingers belonged to whom. I loved playing that game. I so wished we were twins. Still, we were more than siblings; we were the best of friends. We confided in one another, debated political issues, and probed deep philosophical questions about the meaning of life. We also could laugh until we cried at a good joke. “Remember, bud. We have more dancing to do. More contests to win.”

Was it only eleven months ago that he’d call me to ask if I could make it home for theSock Hop at school? “I’d like you to be my partner,” he said. So I brought back the latest Chapel Hill dance steps and we shagged, hustled, and bopped our way through the night while Wild Cherry’s, “Play That Funky Music” and other ’70s hits blasted from the speakers. “Pretzel One,” he called out, and I grabbed his hand behind his back to begin the twisting shag move. “Pretzel Two,” he called again, and I reached behind my back to offer him my hand for the reversal. “Double P retzel,” he whispered for the double-twisting grand-finale move.

“And the first place winners for the 1977 Hickory High Sock Hop dance contest are—Becky and Forest Smith. Come up and get your trophy!” The crowd cheered as Forest kissed my cheek and hugged me, holding my hand as we made our way to the stage.

I rubbed his hand, so warm yet still. “Wake up, Forest, wake up,” I whispered to my brother. But the sleep was too deep.

Rebecca Faye Smith Galli is an author and columnist who writes about love, loss, and healing. Surviving significant losses—her seventeen-year-old brother’s death; her son’s degenerative disease and subsequent death; her daughter’s autism; her divorce; and nine days later, her paralysis from transverse myelitis, a rare spinal cord inflammation that began as the flu—has fostered an unexpected but prolific writing career. The Baltimore Sun published her first column about playing soccer with her son—from the wheelchair. 400 published columns later, she launched Thoughtful Thursdays—Lessons from a Resilient Heart, a weekly column that shares what’s inspired her to stay positive. She also periodically contributes to the Baltimore Sun’s Op-Ed page, Midlife Boulevard, Nanahood, and The Mighty and her memoir Rethinking Possible will be published in June 2017 by She Writes Press. Follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram at @Chairwriter to stay updated on her upcoming memoir, giveaways, special announcements, and her unique insight into resilience and positivity.