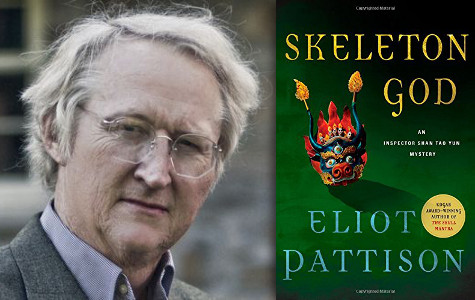

Skeleton God

The Baltimore Post-Examiner is proud to publish an excerpt from Elliot Pattison’s latest book “Skelton God.” In Pattison’s latest book Skeleton God, Shan Tao Yun, the reluctant constable of a remote Tibetan town, has learned to expect the impossible at the roof of the world, but nothing has prepared him for his discovery when he investigates a report that a nun has been savagely assaulted by ghosts. In an ancient tomb by the old nun lies a gilded saint buried centuries earlier, flanked by the remains of a Chinese soldier killed fifty years before and an American man murdered only hours earlier. Shan is thrust into a maelstrom of intrigue and contradiction.

The Tibetans are terrified, the notorious Public Security Bureau wants nothing to do with the murders, and the army seems determined to just bury the dead again and Shan with them. No one wants to pursue the truth–except Shan, who finds himself in a violent collision between a heartbreaking, clandestine effort to reunite refugees from Tibet separated for decades and a covert corruption investigation that reaches to the top levels of the government in Beijing, China. The terrible secret Shan uncovers changes his town and his life forever.

You can purchase the book at Amazon.

Chapter 1

If you would know the age of the human soul, an old lama had once told Shan Tao Yun, look to Tibet. Here at the roof of the world, where humans were so battered, where wind and hail and tyranny had pounded so many for so long, it was a miracle the human spark remained at all. As Shan gazed at the old Tibetan herder beside him, knee-deep in mud, grime covering his grizzled, weathered face, and saw the eyes shining with the joy of life, he knew that he was looking at something ancient and pure. In Tibet souls were tried, and souls were tormented, but always souls endured.

“Put your back into it, Chinese!” the old man gleefully shouted, revealing two missing teeth, then twisted the tail of the yak in front of them.

Shan leaned into the dank hair of the animal’s hindquarters. With a loud bellow the huge yak strained at the mud that trapped it, then sank back.

The four Tibetans he was with were called ferals, not because the old couple, their granddaughter, and her son exhibited the wildness of their remote mountain home, but because they numbered among the few Tibetans who refused to register as citizens of the Chinese government. Their precious bull yak had become mired in the soft mud of a river crossing uncomfortably close to the township’s main road, and Shan, standing up to his knees in the ooze as he pushed the gentle, massive creature, did not miss the worried glances the old Tibetans began casting down the road.

The four Tibetans he was with were called ferals, not because the old couple, their granddaughter, and her son exhibited the wildness of their remote mountain home, but because they numbered among the few Tibetans who refused to register as citizens of the Chinese government. Their precious bull yak had become mired in the soft mud of a river crossing uncomfortably close to the township’s main road, and Shan, standing up to his knees in the ooze as he pushed the gentle, massive creature, did not miss the worried glances the old Tibetans began casting down the road.

“Gyok po! Gyok po!” Trinle, the old grandfather, shouted to Lhamo, his wife, who was tying the lead rope to Shan’s truck. Desperation now crept into his voice. “Hurry! Hurry!”

The young woman in the battered truck eased it into gear, tightening the rope around the animal’s chest, propelling such a shower of mud onto the yak and Shan that the boy in the back of the old pickup burst into laughter. The rope tightened, the yak snorted, and Shan and Trinle strained against the hairy haunches. A single yak, provider of hair for the felt used in tents, blankets, and clothing, milk for nourishment, and dung for fuel, could mean life or death to such impoverished nomads during Tibet’s harsh winters.

The yak grunted and leaned forward, the truck’s wheels found traction, and with a mighty heave the animal broke free, so abruptlythat Shan fell facedown into the muck. He rose to the laughter of Trinle and his great-grandson, who leapt from the truck to give an affectionate hug to the gentle beast. In a moment they were all laughing, the old woman Lhamo pointing to Shan’s mud-covered face, the grandfather scooping up a mud ball and playfully throwing it at his wife. Yara, the woman at the steering wheel, leapt out, her beaded braids swinging, relief shining on her face. “Ati,” she gleefully called out to her son, “when we clean him you can ride him up to the meadow by the—”

A shadow fell over her and she froze.

An army truck, its cargo bay hooded with canvas, was braking to a stop. A young Chinese officer emerged from a gray sedan behind it and studied the faded insignia on the door of the pickup. “I seek the constable of—” He hesitated, consulting a map in his hand. “—Buzhou,” he finished. “We have…” his words drifted away as he took in the yak, now docilely grazing; the old woman, who had fearfully grabbed the boy and began pulling him toward the slope above them; then the two mud-covered figures still standing in the river. As Shan moved upstream to wash in the clear water, the officer decided to address Yara, who was still standing by the vehicle and the only one with clothes that were not filthy. “I am Lieutenant Jinhua,” he announced. “Constable?”

Sensing disaster, Shan gave up trying to rinse away the mud and threw himself into the frigid water. With a shudder he stumbled across the stream to the side of Trinle, who stood still as a statue, murmuring hasty mantras.

“Yangkar,” the young Tibetan woman corrected him. “The town is called Yangkar.”

Shan gazed at Yara in disbelief. Had she not recognized the officer’s gray uniform? Did she not know she was arguing with a knob, an officer of the dreaded Public Security Bureau, whose own patrols had replaced all the road signs with ones that displayed the new Chinese names given to the remote Tibetan towns?

“No, I am certain it is Buzhou,” the officer countered, seeming oddly flustered. He turned the map toward her, then aimed a finger at the Chinese name. “Like I said. Buzhou, Lhadrung County. And my directory says you have a jail.”

Yara’s eyes flared. “Prisoners?” Her gaze moved toward the frightened Tibetans now visible in the rear of the truck, most wearing the fleece coats of the dropka, nomadic shepherds like her own family.

Strangely, the lieutenant took off his hat. “Mere detainees. They are being transported to a facility outside of Lhasa to start a better

life. Too far to travel before nightfall. We just need to keep them together, under control. Accused of no crime.”

“Accused of living a life too far from Beijing’s grasp, you mean,” Yara shot back, in the scolding tone of the schoolteacher she had been before tearing up her identification papers.

Shan urgently pushed Trinle’s shoulder. The old Tibetan turned and saw that his wife and Ati were now leading the yak up the wide grassy slope, away from the road, and hurried after them. “Yara!” he called in a voice full of fear, then turned and ran up the slope. Shan headed to his truck and grabbed the dark blue tunic lying in its bed.

“I have some tea in a thermos,” the Chinese lieutenant offered.

“Good,” the young woman replied, gesturing toward the prisoners, who crowded at the back of the truck, looking out with fearful expressions. “They look thirsty.”

To Shan’s astonishment the officer grinned. “My name is Jinhua,” he declared again. Perhaps thirty years of age, he had a slight build and an almost boyish face, except for its restless, calculating eyes.

Shan slipped on the tunic, straightening it over his still-dripping back as he stepped beside Yara. She turned, saw her retreating family, and slowly backed away, the officer’s eyes still fixed on her. For the first time, it occurred to Shan that the slender Yara, with her high cheekbones and deep, brilliant eyes, was a strikingly handsome woman. He stepped closer, blocking the officer’s gaze.

The lieutenant’s disappointment was obvious. “You?” He frowned. “But you were in the mud.”

“The mud was where I was needed.” Shan, only three months in office, had dreaded contact with Public Security, had even begun to hope that the knobs didn’t even know about his remote hamlet high in the mountains. “How may the constable’s office serve you?”

“We will never make it to Lhasa by dark. The roads are too dangerous at night, so we would have to make a camp in the wind and the cold. But then I saw Buzhou on the map. When I stopped at the turnoff for the town to ask some farmer where I could find the constable, he said you were working down the road.”

As Shan opened the door of his truck, he glanced back at Yara, who was running toward her family now. On the long grassy slope beyond her, a rider on horseback was galloping toward the shepherd family. He pointed to his truck to keep Jinhua’s attention away from the ferals, who otherwise might end up with the prisoners.

“I have two cells designed to hold two prisoners each. You have at least a dozen.”

The lieutenant shrugged. “Through mutual sacrifice our nation will reign supreme,” he replied, reciting the slogan from Beijing’s latest propaganda poster.

Shan pulled his truck onto the macadam, and Lieutenant Jinhua tossed his keys to one of the soldiers and climbed into the cab with Shan. As they threaded their way up the long switchbacks that led to Yangkar’s high valley, the knob looked out the window with the gaze of the inquisitive tourist. After a few minutes he lifted the little Buddha carved of stone that sat on the dashboard.

“Look at the belly on him!” the young lieutenant cracked. “What a curious thing. If they’re going to make an image of their god, why make him so fat and ugly?” he asked as he tossed it from hand to hand. Shan considered snatching it from him. The little figure was a gift from an old hermit, and it was centuries old. “He looks like some lazy old gardener who just woke from a nap.”

Shan, not sure if he was being baited, stared straight ahead. “What a curious thing,” he repeated. “A solitary Public Security officer with half a dozen army soldiers.” Jinhua held the Buddha still and stared at Shan. “A quarter-hour north of here,” Shan said, “you passed the road that would have taken you through the pass to the Lhasa highway. If traffic was light you could have made it to Lhasa by dusk. Even if you hadn’t, there would have been much larger towns, larger jails, and plenty of guesthouses.”

“Blocked by a rockslide,” Jinhua explained, then pointed as they crested the ridge and the ragged little town came into sight at the center of the valley, a pocket of run-down structures framed by barley fields and pastures. “A junkyard at the end of the world. Comrade, you must have really pissed someone off.”

Shan slowed to pass a donkey cart full of yak dung. “Not the end of the world, the top of the world. A paradise of four hundred thirty-two souls. We are so high and remote we escape the shadow of the rest of the world.”

“Four hundred thirty-two Chinese grateful that Beijing is so far away,” Jinhua said, as if correcting Shan.

“More precisely,” Shan rejoined, “four hundred nine Tibetans and twenty-three Chinese, most of who would gladly leave tomorrow if they could. But they took money from the government to be pioneer settlers, and no one can afford to buy out their contracts.” As the knob officer, seemingly not listening, leaned out of the window to watch mounted Tibetans in broad-rimmed hats herding sheep toward the summer pastures, Shan reached under the steering wheel and switched on the flashing light on top of his truck.“Cowboys in China,” the young lieutenant mused. “Who knew? What other miracles do you hide in your township, constable?”

“Life here is just one miracle after another,” Shan said. “You just need to know how to look for them.” He glanced uneasily at Jinhua, who had pulled a map from the dashboard and was studying it. Shan knew from painful experience never to trust a knob who behaved so casually. Even a junior lieutenant had the authority to throw someone in jail for a year on his signature alone.

He slowed as they reached the outskirts of the town, crawling past the large official sign announcing BUZHOU in Chinese characters, with a hand-painted one, in the only language most of the inhabitants could read, fixed below it, declaring BLESSED

YANGKAR. Half a dozen Tibetans on bicycles, having seen Shan’s warning light, rode hurriedly by in the opposite direction. The mechanic in the town’s only garage paused in repairing a tire to stare at their little convoy. Ahead of them in the small town square a young nun halted her work on a little onion-shaped structure with a steeple on it, a small chorten shrine, and rushed to the curb, trying to see inside the truck as it slowed.

Passersby stared silently. All activity in the town had stopped. Suddenly a gunshot broke the silence. Frightened onlookers darted into buildings and alleyways. As Shan slammed on his brakes and leapt out, the soldiers erupted from the prison truck, cocking their weapons and aiming them toward the few remaining townspeople before looking toward their sergeant, who had darted twenty feet away from the truck before stopping.

“Someone threw in a device!” he shouted at Shan. “Lit the fuse and ran!” He waved his still-smoking pistol toward the Tibetans on the street. The sergeant was an older career soldier, probably well aware that Tibetans in the remote mountains had once waged a dogged resistance against the Chinese. “Don’t go up there, you fool!” he warned as Shan climbed in among the prisoners. He watched as an old woman walked along the two benches, pausing by each of the occupants to touch them with smoke from the bundle of incense sticks she now held in her hand.

“Grandmother,” Shan patiently asked, “when you are done may I have that?”

The old woman replied with an uncertain smile. When she handed the bundle to Shan, he cupped the fragrant smoke over his own face before turning. Jinhua stood at the tailgate, studying Shan with an intense curiosity. “Not a device,” Shan called out to the nervous soldiers. “Just some incense, to summon protective spirits.”

He tossed the bundle to the sergeant, who let it drop to his feet, then angrily stomped it with his boot.

Shan guided the truck to the front of the one-story stucco building facing the center of the town square. A small cordon of residents had already assembled by the station’s door. He recognized Mrs. Weng, proprietress of the town’s largest store, Mr. Hui, the town dentist, and Mr. Wu, the town clerk. They had anointed themselves as the Committee of Leading Citizens, an adjunct of the township Party apparatus. All were Chinese.

Shan ignored their approving nods as he led Jinhua inside. He passed through a sparse outer office into the darkened room beyond, where two cell doors hung open. Switching on the row of naked light bulbs that ran down the center of the ceiling, he lifted a uniform cap from the table and tossed it at the figure lying on one of the cell cots.

“Customers!” he called out. “We’ll need more blankets, more spoons, more bowls. More of everything. Bring some pallets from the guesthouse.”

The middle-aged Tibetan on the cot rolled over, rubbing his eyes, then shot up as he saw the soldiers behind Shan. He grabbed the tunic stuffed between bars of the cell and hastily pulled it on.

“My deputy,” Shan explained. “Officer Jengtse.”

Jengtse straightened and awkwardly saluted as Lieutenant Jinhua approached, followed by the army sergeant, then flushed as the sergeant jeered at him and gestured to the prisoners. “Six to a cell,” the sergeant ordered the deputy.

Jengtse, who had served twenty years in the People’s Liberation Army, mostly along the Russian border, dutifully hastened to retrieve the keys from the table.

Jinhua lowered himself into the chair at Shan’s desk and watched with an amused expression as the office, crowded with prisoners and soldiers, gradually assumed a degree of order, with the frightened Tibetans being herded single file into the cells and the soldiers bringing their packs from the truck into the office.

“There is a government guesthouse behind us,” Shan explained to the sergeant as he realized the men were intending to sleep in the station. “More than enough beds.” He saw the skepticism on the man’s hard face. “The cells will be secured. The prisoners are in our care for the night.”

Jengtse locked the cells and turned to Shan with a despairing expression. They had both seen the tags pinned to the clothing of each prisoner, even the two children. Yi, er, san, si. One, two, three, four, and on up to twelve. The prisoners had lost their names. They were part of the wave of displaced persons coming off the high plains, where army patrols had been sweeping, scouring away the nomadic families who had lived there for centuries. When they arrived at the internment camp they would be given new, Chinese names. After a few weeks of reeducation focused on the ever-correct ways of the motherland, the adults would be sent to factories in distant provinces and the children to boarding schools, not to see their parents for years, if ever.

The small door at the back of the cell block suddenly opened. “Shan! Constable Shan!” called the woman even before she had stepped inside. “The dead are rising!” It was Yara, whom Shan had last seen escaping toward the mountains. Tears stained her dusty face. “You must—” Her words choked away as she saw the soldiers. She looked at the prisoners and visibly shuddered. Her eyes welled with moisture and she backed away, leaving the door open as she fled. How could she have made it to town so quickly, Shan asked himself, then remembered the rider who had been galloping toward her.

A surprised murmur left Jengtse’s throat, and he bent to pick up something Yara had dropped. He studied it for a moment, then looked up at Shan in alarm, glanced at Jinhua, and stuffed it in his pocket.

Shan retrieved a key ring from his desk and tossed it to the army sergeant. “The long stucco building along the wall of the rear compound. Washroom toward the rear, bedding in the closet just before the washroom. Our guesthouse.”

The sergeant eyed the keys uncertainly. “The prisoners are in my charge.”

“The prisoners became my charge when you put them in my cells,” Shan rejoined. “You can see they are going nowhere. If you prefer to take them back to your truck and make a camp in the mountains, feel free to do so. But you’d better hurry; you’ll need at least two hours.”

“Two hours?” the sergeant asked.

“That’s how long it will take you to find enough yak dung to keep a fire going during the night. Not much firewood at these altitudes.”

The sergeant gave a discontented grunt, then studied his six weary men. “Bedding in the closet,” he repeated. As he hurried his men outside, Shan turned to Jinhua, still sitting at his desk.

The knob stared at Shan for a moment, then shrugged. “Perhaps there’s something that resembles a café in your metropolis?” the lieutenant asked.

“A noodle shop. At the east end of the square.”

“Fried rice and chicken?”

“Rice comes in once a month, and usually it is gone after the first week. You can cut your noodles into tiny pieces if you are that homesick.” Shan knew better than to goad the young knob, but he resented that a Public Security officer was sitting in his chair, resented that the arrogant young knob had just derailed his efforts to build trust with the local Tibetans, and especially resented being forced to help with the resettlement campaign that was bringing torment to so many Tibetan families. “There’s a small separate apartment at the back of the guesthouse. If you hurry you might claim it before the sergeant does.”

Jinhua’s cool grin sent a shiver down Shan’s spine. The knob bowed his head as if surrendering, then rose and stepped out to the street. Shan returned to the cell room and found Jengtse staring at the object Yara had dropped. “Old beads,” the deputy observed. It was a mala, a Buddhist rosary. “Bone. Made of bright white bone,” he added pointedly and dropped them on the table in front of Shan.

But the beads weren’t white; they were so pink Shan at first thought they were made of coral. As he lifted them from the desk his heart went cold. The bone beads, each intricately carved into the sacred image of the eternal knot, were sticky. They were covered in blood.

“Nyima!” a woman gasped from the nearest cell. She was staring at the beads.

“Nyima?” Shan asked his deputy.

“The old hermit nun who comes to town on market days,” Jengtse explained. “She spins an old prayer wheel covered with dancing leopards and promises a thousand turns for you if you drop a coin in her basket.”

“Where does she live?” Shan asked.

“I don’t know exactly. In the mountains north of here. Some call her a witch because of all the old rituals she performs. The old ones still buy curses and charms from her.”

The mountains to the north. She could be anywhere in a hundred square miles.

Shan realized that Jengtse was staring over his shoulder. He turned to see the woman who had spoken the nun’s name reaching out through the bars. She was staring at the bloody rosary.

“Where did these prisoners come from?” Shan asked his deputy.

Jengtse shrugged. “The sergeant just said the mountains to the north, from the summer pastures, I guess. Easy to round them up there since they have to go through those high passes. Like funnels, just deploy squads at the mouth of the pass and you’ve got them.”

The woman, in her late thirties, looked up at Shan in silent pleading. Her eyes, welling with tears, were of an unusual green color. “Do you know the nun?” he asked as he approached.

“Nyima,” the prisoner said again, and snatched the beads out of his hand.

“Where is she?” Shan asked, but the woman seemed not to hear him. “Nyima,” she repeated in an anguished tone, then retreated to one of the cots and sat with the beads stretched between her fingers. When he asked again, more loudly, she sobbed and buried her head in her hands.

“Find that woman who left them,” he said over his shoulder to Jengtse. “Her name is Yara.”

But his deputy was not there. Jengtse stood at the outer door, trying to push someone away. “He’s Chinese, you fool!” Jengtse said in an urgent whisper. “Meet me in the stable.”

Shan pushed down his anger and stepped past his deputy. Rikyu, the young nun who maintained the town shrines, was standing outside. She quickly buried her hand in the folds of her robe. Shan just as quickly pulled her arm away. Rikyu was holding a small, once elegant prayer wheel, now smashed nearly flat. Its copper surface was embossed with silver images that appeared to have been dancing leopards.

“Where?” Shan demanded. “Where is Nyima?”

“I don’t know,” the nun said. “She sleeps in a cave up past the old salt shrines.”

“Can you get me there?”

Rikyu gave a nervous nod. “At the end of the road they use when they truck sheep out of the mountains, just before the pass to the Lhasa highway.”

“Show me,” Shan said, pushing the nun inside and pointing to a map pinned to the wall. Rikyu indicated a circuitous dotted line that ran from the highway north of town and ended at the base of a steep ridge. “She probably just fell. I will go see her. Not for you to worry about,” she said, meaning it was Tibetan business, for Tibetans to worry about.

He extended his hand for the ruined prayer wheel, then pointed to a jagged pattern in the soft metal. “A heavy boot did that. Not the shoe of a nun.”

Rikyu kept her eyes lowered. Neither the nun nor his deputy trusted him. They knew that if an unfamiliar Chinese constable showed up by himself in the mountains, the few Tibetans who lived there would likely scatter like deer. “Go find Mrs. Weng,” he instructed Jengtse. “Tell her the Committee of Leading Citizens has been called to duty.”

Jengtse grimaced but obeyed, muttering his disapproval as he left the building. Rikyu hesitated a moment, as if seeing something new in Shan’s eyes. During Shan’s first weeks in office the nun had kept her Bureau of Religious Affairs registration, her license to wear a robe, pinned conspicuously to her clothing, and behaved like a submissive servant whenever Shan approached. Shan had finally taken her into the office and made a duplicate of the license on their creaky old copier, then told the nun he would just keep it on file so the nun would not need to display her papers. Afterward she had seemed even more skittish, and Shan had realized Rikyu had taken his action as a threat.

Ten minutes later, Mrs. Weng had assembled the officers of the committee in the station. Shan shuddered at their mounting enthusiasm as he described what he had in mind. “A full bowl of noodles to every prisoner, and let each, one at a time, use the

washroom before eating.” He pointed to the keys hanging on a peg by his desk. “No one else in the building while I am gone. And no, Mr. Hui,” he said as he saw the dentist’s jealous glance toward the weapons locker. “No firearms. No one in the cells committed an act of violence. A bowl of noodles for each prisoner,” he repeated to Mr. Wu, the town clerk, whom he took to be the most dutiful of the three. “And tea for all. My surveillance cameras will tell me if you fail to comply.” The committee members stiffened and nodded their understanding. Mr. Wu cast a furtive glance toward the ceiling as if looking for cameras, then offered a clumsy salute.

“Bring a medical kit,” Shan said to Jengtse, “and some blankets.”

* * *

As they left town, Jengtse carefully arranged the little Buddha on the dashboard so the god was looking ahead of them. “We don’t have cameras,” he observed.

“So add it to the next requisition list. And fingerprint kits.”

“You should be more realistic,” his deputy said. “Maybe pencils and paper, but anything more and they will just—” His voice trailed away as he pointed toward the slope above town. Shan pulled over and focused his binoculars on the pass. Figures on horseback were hurrying up the long slope from below, converging on the pass that led into the high ranges. Shan looked through the back window. Rikyu, sitting on a bundle of blankets in the bed of the pickup, was pointedly ignoring Shan as she pressed her mala to her lips. She was frightened. The dead are rising, Yara had said.

The old truck wheezed and groaned as it climbed the overgrown road indicated by Rikyu. It was a region Shan had not yet explored, the far northwestern tip of Lhadrung County, known for its high, inhospitable ridges that rose up like fortress walls to isolate the lands above. The road faded into grass-lined ruts, then abruptly ended at a broad clearing surrounded by rock outcroppings.

“She lives in a cavern on the first flat, by the ice caves,” Rikyu explained as she climbed out. Shan followed her arm toward two flats above them, separated by a steep embankment. He made out the heads of several people who were watching them from the second, higher, flat. Rikyu cinched up her loose robe and began running up the worn trail.

The old nun lay in the narrow gap between two outcroppings near the top of the path to the second flat, a surprisingly broad, level plateau that extended for nearly half a mile. She had been struck on the head with a vicious blow that left a ragged, open cut across one temple. Blood oozed down her jaw and onto her neck. One hand was bloody, with two fingers bent unnaturally, obviously broken. Her robe was spotted with blood. Rikyu already sat beside her, clasping the woman’s uninjured hand. “Om mani padme hum,” Rikyu murmured, the mantra that invoked the Compassionate Buddha.

Shan knelt at the nun’s other side. “Grandmother,” he asked in Tibetan, “who would do such a thing?”

Nyima pulled her hand from the young nun and waved it back and forth as if to dismiss him. “It’s nothing, a trifle,” she said in a cracking voice. “Find my donkey. The amchi will have me right,” she continued, using the term for a traditional Tibetan doctor.

Shan was aware of no doctor in Yangkar, Tibetan or otherwise. “I am not the one who needs help. They need to find their way, to be able to speak with the ghost. So he can take us to his paradise.”

Shan followed her gaze toward a small group of Tibetans thirty yards away, gathered around a patch of ground covered with tufts of grass and lichen. “Hal lei lu jah,” the old nun murmured, “hal lei lu jah.” It was not a mantra Shan had ever heard.

He felt conspicuous, out of place, as he approached. The old nun did not want his help. None of the Tibetans wanted his help. Not for the first time Shan silently cursed Colonel Tan, governor of Lhadrung County, for forcing him into the blue tunic. He longed for the tattered work clothes he had worn for years, clothes that would have allowed him to sit beside these simple, reverent Tibetans. A woman retreated behind a sturdy-looking herder as they saw Shan. Two children were quickly sent away toward the sweat-stained horses now grazing at the end of the plateau.

“She found you, constable?” one of the old men asked. To his surprise Shan recognized Trinle, who now glanced with anticipation over his shoulder. “Yara did not join us,” Shan replied, considering a mental map as he studied the wary old herder. The roads had looped around the base of the huge mountain, but there would have been tracks leading directly over the ridges that would have been much shorter. Trinle had been in a hurry even before the truck had stopped. They had been racing toward this very place, but not because they knew Nyima had been attacked. Shan nodded toward the patch of ground the Tibetans were staring at. “What have you found?”

Trinle did not want to answer. He glanced uneasily at his wife Lhamo, who stood with the ring of Tibetans, then stared at a black crack in the ground.

“It has found us!” cried out a middle-aged man Shan recognized as a farmer who lived near the town. “A ghost has summoned us to its entrance! A bayal!” he exclaimed, referring to one of the mythical paradises that were said to be hidden underground, revealed only to those of great virtue. “Nyima heard it call out from the ground yesterday, then again this morning. Hal lei lu jah,” the man said and touched the gau, the prayer amulet, that hung around his neck. Knotted into the cord of his gau—knotted or stuffed into every gau visible to Shan—was a twisted piece of green paper.

“I don’t understand,” Shan said.

“It is for the pure of heart,” the woman beside the farmer replied, as if to explain Shan’s ignorance.

“Hal lei lu jah,” the farmer repeated. “It must be what the ghosts say, to summon us. Yesterday, and again today, the same time each day. We have all come to hear it, so we can learn their secrets at last!” The old man pointed to the narrow opening in the earth. “At last it is time for us to cross into it!” He turned to the woman beside him. “Should we prepare a bag of food for the journey?” he asked her.

Shan paced along the little crevasse, which revealed nothing but deep shadow below, then surveyed the plateau. “What is this place?” he asked. The Tibetans near him looked away uneasily.

“The Plain of Ghosts, of course,” Lhamo said. “No one would ever come here. It’s taboo. Except now we are called, after all these years.”

Shan dropped to his knees, exploring the grass-lined edge of the opening, then pulled up a tuft of grass to reveal the straight edge of a carefully chiseled stone. The tuft had not been rooted there; it had only recently been pushed into the loose soil covering the stone as if to conceal it.

“Blessed Buddha! It’s a door!” the farmer exclaimed and dropped to his knees, pulling more tufts. His wife knelt beside him to help scoop away the soil, then a third man bent to help. Soon they had revealed a carefully cut stone slab, eight feet long and nearly six wide.

“Terme!” one of the women said, meaning Buddhist relics and teachings that had been buried or hidden in Tibet during earlier centuries, waiting to be found by the devout of the future.

“A bayal,” the farmer insisted. “The paradise we have waited for.”

As Shan walked around the slab a great foreboding seized him.

Rikyu, the young nun, had run to Nyima to report the discovery and was now sprinting back, her robe streaming behind her.

“Don’t!” she gasped as she reached Shan. “You can’t!” She grabbed his arm. “Make them stop!”

“Who attacked her?” Shan pressed. “Why assault an old nun?”

Rikyu’s anxious gaze turned to the circle of Tibetans. The farmer was arranging men at either end of the slab. “No! You don’t understand!” the nun shouted. “You must stop!” From beyond them came a frantic cry, then weeping. Nyima was trying to crawl toward them but had collapsed in pain. “Stop!” she shrieked from the ground. “You’ll bring the long night back!”

“Stop!” Jengtse took up the cry, with surprising vehemence. He grabbed the arm of one of the men, who resentfully shook him off.

No one seemed to hear. The farmer grabbed a shepherd’s staff, inserted it into the crack, and began prying up one edge of the stone.

“Please don’t!” Rikyu pleaded. “I beg you! He is a saint!”

The farmer with the staff gestured for the other men to grab the slab as it rose on his lever. “Not even a saint could get out of that hole by himself,” he muttered.

Suddenly Shan saw Lieutenant Jinhua standing a few feet away, staring with a predatory expression at the stone slab. “Wait!” Shan called out, and pushed through the Tibetans to intercept the knob officer.

But it was too late. The lever had raised the stone high enough for the excited Tibetans to grip it, and they were lifting the slab. They groaned, staggering under the weight, then lowered it onto the grass beside the hole.

One of the women screamed and staggered backward. Several of the Tibetans began running away. Others grabbed their prayer amulets or rosaries and began urgent prayers. Trinle collapsed onto his knees, staring wide-eyed.

The lama lay in a wide tomb carefully lined with more stone slabs, his hands folded over his belly, the lids of his closed eyes painted vermilion, his mummified face, like all his exposed skin, covered with gold gilt. It was a burial of the distant past, probably hundreds of years old, the kind indeed reserved for the most saintly of teachers. The mantras changed and grew louder. The remaining Tibetans weren’t making the traditional request for compassion now, they were asking for forgiveness.

Only Lieutenant Jinhua moved, shoving past the stunned Tibetans. He knelt at the edge of the tomb, then lowered himself onto his belly to study the mummy. “He was calling out,” the knob observed.

“There was a sound from the grave, that’s all,” Shan said. “An animal fell inside, perhaps.”

“No,” the knob insisted. “I mean he was calling out.”

Shan followed Jinhua’s gaze to the folded hands. He stopped breathing for a moment, then, as the lieutenant twisted and lowered his legs over the edge of the tomb, Shan roughly grabbed his collar. He pulled Jinhua back, then quickly dropped into the tomb himself. He pulled out his own prayer amulet, as if to show it to the long-dead lama, then, pushing down some of the tattered ornate

rug that covered much of the body, so large it was bunched against the sides of the tomb, he stepped closer and reached out. Clenching his jaw, he pried up the topmost hand. The long-dead lama was holding a cell phone.

Shan retrieved the device and, ignoring Jinhua’s outstretched hand, pressed the large green button. As the screen sprang to life, he stared at it, disbelieving. All the words were in English. He pushed the button for the ringtone. “Hallelujah,” sang a chorus.

He looked up into a circle of confused faces.

The young nun was the first to find her voice. “Cover him! He is a saint, not a spectacle!”

Shan let Jinhua reach down and grab the phone out of his hand, then lifted the old carpet in each hand to fling it forward, and froze.

The Tibetans, including the nun, backed away, gasping, some now clutching their bellies. Jengtse cursed and lifted the staff as if for protection. Shan, dropping the carpet, found himself flattened against the end of the tomb, his heart thundering.

“Like you said,” Jinhua observed in a tight voice, “just one miracle after another.”

The hideous, desiccated body Shan had exposed to the left of the lama was that of a Chinese soldier, dead not for centuries but probably for decades. The one on the right was of a Western man, dead for only hours.

Copyright © 2017 Eliot Pattison.

Described as “a writer of faraway mysteries,” Eliot Pattison’s travel and interests span a million miles of global trekking, visiting every continent but Antarctica. An international lawyer by training, he received “the Art of Freedom” award along with Ira Glass, Patti Smith and Richard Gere for bringing his social and cultural concerns to his fiction, published on three continents. He is the author of thirteen mystery novels, including the internationally acclaimed Edgar award-winning Inspector Shan Series, set in China and Tibet and the Bone Rattler Series, set in Colonial America. His books have been translated into over twenty languages.

A former resident of Boston and Washington, Pattison resides on an 18th century farm in Pennsylvania with his wife, three children, and an ever-expanding menagerie of animals.