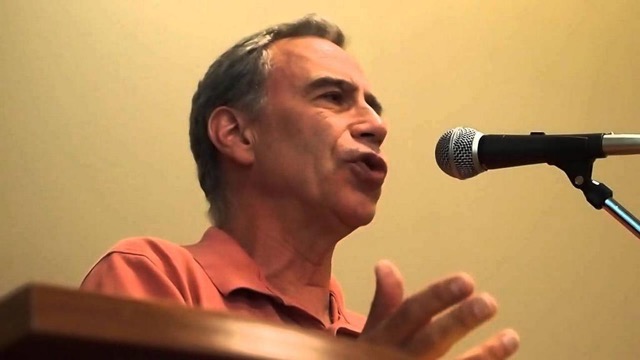

Joe Uehlein still fighting for sustainable jobs and a living planet

Joe Uehlein, veteran trade unionist and musician, co-founded the Labor Network for Sustainability to bring labor and environmental activists together.

There are loads of unheralded heroes from steel mill towns. But Joe Uehlein, the accomplished union organizer and musician, who has persisted for decades at an extraordinary challenge—joining the labor and environmental movements—is certainly one of the most creative and tenacious.

Today, as President Donald Trump courts the nation’s building trades unions, promising to build more pipelines, fire up shuttered coal mines and open millions of acres of federal land to hydraulic fracturing (fracking) for natural gas, Joe Uehlein’s hard-fought vision of sustainable jobs and a living planet is more critical than ever.

He grew up 20 miles outside of Lorain, Ohio, once known as Steel City. His father, Julius Uehlein, was one of the original organizers of the United Steelworkers of America, who, in his 70s, led a successful battle to raise Pennsylvania’s minimum wage. Joe’s mother had been an activist too—an organizer for the clothing workers union and editor of the CIO Sun, a labor newspaper in Cincinnati.

Joe, now a Takoma Park, Md. resident, walked the picket line with his father during the 1959 national steel strike. And he sang labor songs as Julius played the guitar at union picnics. From those days on, Joe—who has played music all over the world and conspired with headliners like Steve Earle, Tom Morello, Billy Bragg and the Dropkick Murphy’s—has lived the lyrics of a song, “You Can’t GiddyUp by Sayin’ Whoa!” he wrote for Sweet Lorain, the most recent CD produced by his band, the U-Liners:

“Well people often tell me you can’t do things so fast. Take it slow, be real

careful, can’t upset the past. But I just don’t know, I don’t see things that way.

Best I can can tell we’re out of time, so here’s what I’ve got to say, ‘You can’t

Giddyup by sayin’ whoa, Ain’t gonna get ya where you want to go.’”

Here’s a guy who, in the 1990s, played a pivotal role, assisting the United Steelworkers in the successful battle against the Ravenswood Aluminum Company in West Virginia after the firm, seeking to cut wages and benefits, locked out 1,700 Steelworkers and hired replacements to run the plant.

A 1992 New York Times story describes Uehlein’s innovative corporate campaign that took the fight to one of the company’s prime investors, Marc Rich (yeah, the guy Bill Clinton pardoned) who had fled the U.S. for Switzerland after being convicted of fraud and tax evasion. Uehlein, then working for the Industrial Union Department, AFL-CIO, the successor of the CIO, followed Rich to Europe, building support from unions across the continent, helping nail down a pivotal labor movement victory 19 months later as replacement workers were forced out and strikers came back to work.

Here’s a 50-year member of the American Federation of Musicians who helped marshal union brigades in the 1999 “Battle of Seattle” protests against the World Trade Organization. Here’s a prophetic voice who, in a 2009 article in The Nation, set down a warning for the body politic that went tragically unheeded: “It is a basic principle of fairness that the burden of policies that are necessary for society–like protecting the earth’s climate–shouldn’t be borne by a small minority who happen to be victimized by their side effects. Unless workers and communities are protected against the unintended effects of climate protection, there is likely to be a backlash that threatens the whole effort to save the planet.”

“As a kid, I fished in Lake Erie for yellow perch, but then I started seeing signs warning me not to eat the fish I caught,” says Uehlein. In 1969, his concerns over water quality were deepened when a spark from a passing train ignited an oil slick on the Cuyahoga River. Cleveland’s River on Fire garnered international attention and heated up a burgeoning environmental movement.

Uehlein moved with his parents to Pennsylvania. At age 17, he got a job in an aluminum mill in Mechanicsburg, learning about life on the shop floor and participating in two strikes before Hurricane Agnes flooded out the mill in 1972.

Joe got on the books with Laborers International Union of North America (LIUNA) Local 158 on heavy and highway construction. “I worked building the Texas-Eastern pipeline as it wound its way through the rolling hills of Central Pennsylvania,” says Uehlein. In the 1970s, he joined the concrete crew constructing the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station. “I crossed picket lines set up by folks protesting nuclear power. My local produced bumper stickers saying, ‘Hungry And Out of Work? Eat an Environmentalist,’” he says.

In 1975, Uehlein was hired as an organizer by the Industrial Union Department, AFL-CIO (IUD), organizing manufacturing workers across the Southeast, later helping plan the boycott of J.P. Stevens, the 11-year North Carolina textile mill battle portrayed in the movie, “Norma Rae.” The same year, he engaged in his first joint effort with environmentalists.

A group of activists, Environmentalists for Full Employment, had come together demanding to be included in the Full Employment Action Council, composed primarily of labor leaders and community organizers. Uehlein began to work with the group and encouraged the IUD to offer financial help even while he was learning new lessons at work.

As private industry and the nation’s workforce were besieged by economic and political challenges in the early ‘80s, Uehlein and others knew that wholly new approaches to organizing were essential. He says cultivating creative approaches was inherited from his parents. “My parents called the CIO “Community in Operation,” he says.

Uehlein traveled to Tupelo, Miss. where the IUD was looking to organize several industrial plants. The IUD set up a social services agency to help local workers with childcare, addiction counseling and other needs to help break down anti-union stereotypes.

Ultimately, Uehlein’s music help break the ice, too. He won first prize and area newspaper coverage in an amateur bluegrass competition, singing labor songs like “Sixteen Tons.” Later, after getting a call asking him to play at President Jimmy Carter’s annual Labor Day picnic, Uehlein won an invitation to the popular Buddy & Kay Bain early-morning TV show. Since workers headed to early morning jobs were the show’s primary audience, he parlayed his notoriety into new contacts at the plant gates and more doors opening when making house calls. The IUD won campaigns in local shops.

These innovative tactics, some applied during the Ravenswood Aluminum campaign helped him win election as secretary-treasurer of the IUD.

In 1982. The IUD, along with some affiliates like the Steelworkers and groups like the National Wildlife Federation, Friends of the Earth and the Sierra Club formed the first national labor-environmental coalition called the OSHA-Environmental Network. Uehlein served as its field director for three years.

Like all organizers, Uehlein was a road warrior, winning some battles, but taking sometimes severe casualties in others, like the strike at Phelps-Dodge in Arizona where copper miners suffered a tragic defeat after the company hired strikebreakers and hundreds crossed the picket lines leading to 13 unions decertifying in 1986, as much a low-point in labor annals as the Ravenswood campaign was high.

In 1988, Uehlein heard about the U.N. Commission on Global Warming and figured the U.S. trade union movement should be on board. He ended up serving on the commission for 17 years.

The next year, the Exxon Valdez oil carrier dumped nearly 11 million gallons of oil into Prince William Sound, Alaska. Seeing the devastation faced by fishermen, Uehlein attempted to organize delegations of union presidents to express their solidarity with them. The effort failed, but Uehlein’s work in Alaska garnered a valuable supporter.

Joan Bavaria, the president of Trillium Asset Management, spearheaded the Valdez Principles, a standard for comparing the behavior of corporations on the environment. They evolved into the Coalition of Environmentally Responsible Economies (Ceres). Uehlein became a founding member of the Ceres board.

“I wanted the federation to sign onto Ceres’s shareholder resolutions and, in return, have environmentalists sign onto ours,” says Uehlein. The federation was unconvinced at the beginning but later signed on.

Uehlein jumped to other labor trouble spots like the bitter five-month 1990 strike at the New York Daily News, where he helped workers match wits with companies trying to replicate the crushing blow at Phelps-Dodge.

The U.N. Commission on Global Warming was developing a framework convention on climate change. In 1997, after eight years of meetings, the commission sponsored the first meeting of the Kyoto Protocol, a global environmental pact. Uehlein allied with other global trade unionists focusing on climate change.

Knowing the AFL-CIO, under pressure from unions engaged in fossil fuel production and generation, wouldn’t support the protocol, he argued for the federation to take a neutral stance. He was rebuffed when the AFL-CIO issued a statement calling upon the U.S. president not to sign the pact.

Uehlein only became more determined. “It is in our core self interest as a labor movement to become a part of the climate protection,” he says. But Uehlein has always seen the divide between labor unions and environmental activists as a mutual problem.

Environmental organizations, he says, “have too often ignored the very primacy of work in peoples lives and the central role of work and workers in public life and decision making.” American trade unions, he says, have “focused largely on protecting past gains rather than on a strategic response to the economic and environmental challenges they face.” Uehlein says both movements “suffer the loss of effectiveness resulting from the gap in their perspectives.”

In 1999, Uehlein helped coordinate the massive protests against the World Trade Organization in Seattle. The “Battle of Seattle” was a decisive moment, building respect among trade unionists for political activists taking on corporate-dominated trade and economic policies while turning young activists on to the value of working with and for unions.

Uehlein left the AFL-CIO in 2005 to devote full time to environmental/labor activism. He spent a year meeting with union presidents about climate change. While every president knew about climate change, he says, “none of them thought climate change was an issue their union should be active on.

Uehlein shared a six-page paper summing up his labor leader interviews with with the Union of Concerned Scientists, on whose board he served. UCS shared the paper with the Energy Foundation in San Francisco, which awarded Uehlein a healthy grant to conduct a power structure analysis of labor unions’ approach to jobs and the environment. He hired three seasoned activists, researchers and writers to help out, Jeremy Brecher, Brendan Smith, and Tim Costello.

“We assessed the unions’ decision-makers and self-interests,” says Uehlein. “But we also wanted to answer the question, ‘How does labor change on big social issues.’” Some unions, he says, had historically conservative postures, but ended up changing their positions on issues like civil rights, war, trade and globalization, immigration and single-payer healthcare. “What strategies would be needed to move them on climate change?”

Uehlein put his newfound knowledge to work as the senior strategic advisor to the Blue-Green Alliance, launched in 2006 by the United Steelworkers and the Sierra Club. The alliance brought together environmentalists and several unions, initiated important ad hoc efforts on issues like trade policy and sponsored yearly “Good Jobs-Green Jobs” conferences. He took inspiration from dozens of local unions and some internationals that support renewable energy development and training their work forces for new technologies and jobs.

But for Uehlein, the urgency to address both rampant economic inequality and the rapid advance of climate change required “more than ‘building bridges’ across the movements through individual legislative initiatives or investment projects.” There is a critical need, he says, to form a shared vision for the future of the economy from the ground up. “There has been a ‘silo approach’ to engagement between environmentalists and labor,” says Uehlein. “The silo approach has failed and will not succeed in meeting the timeline science suggests we’re looking at on climate change.”

So, in 2007, Uehlein joined Brecher, Smith and Costello in founding the Labor Network for Sustainability (LNS). The group’s purpose, explained in a video featuring Uehlein is to “bring environmentalists and labor movement leaders together in a series of structured conversations with the goal of building and articulating a vision for a progressive economic agenda to build a just and sustainable economy.”

LNS is joining with the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University to deepen conversations between labor and the environmental community in creating a series of meetings called “Making a Living on a Living Planet,” designed to tackle difficult issues, like” the Keystone XL pipeline, and strategies for coalescing on climate change.

The conversations consider the potential for “just transition” where workers who are losing their jobs in one section of the energy industry are afforded income maintenance for four years, health care and pension maintenance and training for new careers. “No worker or community should be the road kill on the path to a new economy,” says Uehlein.

Europeans are ahead of their U.S. counterparts on transition planning. But, he says, solid domestic models are being created, like the negotiated settlement between Pacific Gas and Electric Co. and International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 1245 and Friends of the Earth over the closure of California’s Diablo Canyon Nuclear plant.

In 2011, Uehlein opened a window to his heart when he was asked by celebrated climate change activist Bill McKibben to sign a call for civil disobedience to block the building of a pipeline designed to carry tar sands oil from Alberta to the Gulf of Mexico. “Opposing the pipeline,” Uehlein wrote in an open letter, “might strain ties with unions that I’ve worked with and been part of for my whole adult life.” And yet, he says, “The pipeline might be a tipping point that could hurtle us into ever more desperate acceleration of climate change.”

Uehlein signed the call and explained his decision: “To those who might get a job on the pipeline I say: We’re blocking the pipeline to save your future too. But I know I won’t be able to look you in the eyes if I and those I am marching with don’t fight to make sure there are decent jobs for you and your kids—building the kind of world we need…I am marching not against the labor movement but for the labor movement, the kind of labor movement my parents fought for and I have always in my heart believed it to be.”

Today, the labor and environmental movements face an administration that denies the very existence of climate change and a Congress determined to further weaken organized labor and environmental regulation.

Uehlein, a father of three, a student of history and co-founder of the Labor Heritage Foundation, is both sanguine and determined. Drawing inspiration from the broad resistance against the Trump administration’s reactionary agenda, he supports Brecher’s call for a campaign of “Social Self Defense,” similar to the resistance that developed in Poland 40 years ago and led to the Solidarity Movement.

“We will have some tough sledding,” says Uehlein. “The nation and the planet will recover if we cease greenhouse gas emissions and defend the most vulnerable among us. I am inspired by the young activists today and I believe victories will come if we believe in and act upon a broad vision of progress.”

The Labor Network for Sustainability’s co-founder Brendan Smith says activists, young and old, should call on Uehlein’s experience and perspective. Smith says, “Joe’s got both the vision and the organizing chops the world desperately needs right now. More than anyone else I know, he’s able to leverage the escalating threats of climate change and inequality into a powerful message of solidarity that brings people from different sides of the fence together. If the labor movement wants to survive, let alone be relevant, in the coming decades of turmoil, I’d have Joe on speed dial.”

Len Shindel began working at Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point Plant in 1973, where he was a union activist and elected representative in local unions of the United Steelworkers, frequently publishing newsletters about issues confronting his co-workers. His nonfiction and poetry have been published in the “Other Voices” section of the Baltimore Evening Sun, The Pearl, The Mill Hunk Herald, Pig Iron, Labor Notes and other publications. After leaving Sparrows Point in 2002, Shindel, a father of three and grandfather of seven, began working as a communication specialist for an international union based in Washington, D.C. The International Labor Communications Association frequently rewarded his writing. He retired in 2016. Today he enjoys writing, cross-country skiing, kayaking, hiking, fly-fishing, and fighting for a more peaceful, sustainable and safe world for his grandchildren and their generation. Shindel is currently working on a book about the Garrett County Roads Workers Strike of 1970 www.garrettroadstrike.com.