Freddie Gray’s Death Five Years Ago Was Not the Sole Reason Behind Baltimore’s Riots

BALTIMORE — In our time of enforced isolation, we’re as quiet here as any American city, and maybe more reflective. It’s the five-year anniversary of the death of Freddie Gray and the street violence that followed.

This city has had an anxious heart ever since. In countless black neighborhoods, tension with police has not abated. Downtown restaurant and bar owners tell you they’ve never fully recovered from the days of rioting. Nervous suburbanites tell you they haven’t gone downtown since the troubles, and never will again.

And all of this was true even before the coronavirus struck.

The Freddie Gray riots erupted mainly in a pocket of impoverished West Baltimore, but the “downtown” characterization stands for something else – the ongoing racial anxiety in a majority-black city, expressed only partly in the daily street confrontations between law enforcement and those citizens who may, or may not, be making trouble.

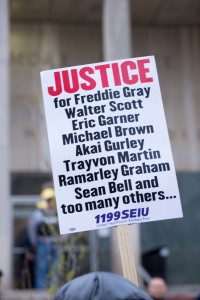

The death of young Gray, after he’d been taken into police custody, happened in the midst of an awful season of white police killing young black men all across America. Some of those killings were captured on video and shown in quick, edited clips. But, in Gray’s case, the ensuing riots were shown in real-time, over several days, and exposed long-simmering troubles that exploded in front of a whole nation of TV watchers.

This city became the face of racial tensions that touch countless American communities.

But it was more than the daily street antagonism that was revealed. Ultimately, this was an expression of entrenched historic gaps between whites and racial minorities that touch every aspect of daily life.

In Baltimore, with its 63 percent African-American population, the median white household income is nearly double the income of blacks. Black unemployment is three times higher than whites.

Roughly one-third of black households have zero net worth – compared to 15 percent of whites. About 60 percent of whites in Baltimore own their own home, but only 42 percent of blacks. Roughly 85 percent of those arrested and jailed each year in Baltimore are black.

In the West Baltimore of Freddie Gray and the ensuing rioting, median household income is $29,000 a year – compared with $73,000 for white families across Maryland. In that same West Baltimore, 90 percent of children in public school qualify for free lunches.

Freddie Gray was only a sliver of a cracked mirror’s reflection of all of this – not only the raw numbers, but the resulting anger and anxiety.

In the current coronavirus situation, we’re getting variations on the awful divide. You might expect a heavy percentage of black people contracting the virus in the city, which is nearly two-thirds African-American.

But, statewide, it’s the same. In majority-white Maryland, at week’s end, there were 6,046 confirmed cases (and 289 deaths) among blacks, and 3,830 cases (and 275 deaths) among whites.

Why would blacks have such an out-of-proportion rate in Maryland – and across the nation? Disproportionately, they’re the ones who don’t have jobs which can be done from a home computer. They’re the ones riding crowded buses and trains to hospitals and grocery stores and such, where their jobs involve lots of people in dangerously close contact.

And so, in a time of enforced quiet, maybe we’ll reflect on the troubles of five years ago – and realize it was more than poor Freddie Gray’s death that prompted so much violence.

And maybe we can figure a way for all of us, whatever our race, to find common ground once we re-emerge from our isolation.

Feature Photo: CVS store goes up in flames as police are ordered to stand down against the rioters. (Screenshot)

Michael Olesker, columnist for the News American, Baltimore Sun, and Baltimore Examiner has spent a quarter of a century writing about the city he loves.He is the author of several books, including Michael Olesker’s Baltimore: If You Live Here, You’re Home, Journeys to the Heart of Baltimore, and The Colts’ Baltimore: A City and Its Love Affair in the 1950s, all published by Johns Hopkins Press.