Turner Station salutes ‘Henrietta Lacks’ film

Tens of thousands of activists were returning home April 23 on Interstate 95 North, wringing out the wet from Washington, D.C.’s March for Science, checking their cell phones to find their place in history.

Minutes off their route, forty-five miles up the road, in Turner Station, a historic African-American community built around a Baltimore County steel mill, more than 250 current and former residents and friends were lining up for hot dogs, soft drinks and cookies at the Fleming Senior Center to hear a story of science.

Word had issued from the community’s seven churches Baltimore’s onetime news anchor Oprah Winfrey would be appearing on a big screen, zealously memorializing Henrietta Lacks, a Turner Station heroine. Lacks occupies an unrivaled, unique link to medical research. But she also might be the impetus for the revival of a community cast into uncertainty by the decline of industrial Baltimore.

Word had issued from the community’s seven churches Baltimore’s onetime news anchor Oprah Winfrey would be appearing on a big screen, zealously memorializing Henrietta Lacks, a Turner Station heroine. Lacks occupies an unrivaled, unique link to medical research. But she also might be the impetus for the revival of a community cast into uncertainty by the decline of industrial Baltimore.

Henrietta Lacks died of cervical cancer at age 31. Since her death, her cells have been the subjects of more than 74,000 studies. But it wasn’t until 1973 that her children even knew their mother’s pivotal role, one that was recounted in Rebecca Skloot’s bestseller, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” and the just-released HBO Films production by the same name.

“Getting closure is deep,” said Eric Smith, 45, who stood near the door of the senior center. “Henrietta Lacks’s family went through so much adversity,” said Smith. “But they were able to come together and show that one person can do so much.”

The film spares nothing of the family’s adversity as Skloot, a white science writer, shows up to mine their story. Baltimore’s red brick row houses and Lacks’s ancestral cabin in Clover, Va. form the backdrop for the struggles of a motherless family. Winfrey, as Henrietta’s youngest daughter, portrays their raw battle against a host of fiends. Mental illness. Prison. Rape. But she and Henrietta’s descendants never let go of the fight for truth.

The film opens with clips of physicians at Johns Hopkins Hospital bragging about their experiments with Lacks’s cells, named HeLa. It’s clear as the alcohol in the examining room they never thought twice why an African-American family, located an easy 15-minute streetcar ride from the hospital’s venerable dome would be interested in cells or science.

How incredibly wrong they were. Even though the family never derived a penny from Hopkins for HeLa, they continued to fight. And four years ago, 62 years after Lacks’s death, her family came to agreement with the National Institutes of Health giving them a measure of influence over how her genome is used. ”In 20 years at N.I.H., I can’t remember something like this,” the institute’s director, Francis S. Collins, told The New York Times.

Lacks’s family filled up rows at the senior center, cheering her grandson, Alfred Lacks Carter, who introduced the film. They and the entire audience cheered again at an announcement that Henrietta Lacks’s great granddaughter has just entered nursing school, aided by a scholarship set up by a foundation established by author Skloot. After the showing, several attendees lined up to pose for photos with Lawrence Lacks, Henrietta’s eldest son, who is prominently featured in the film.

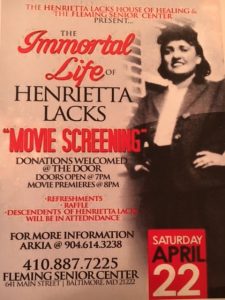

The Henrietta Lacks House of Healing sponsored the film showing, following its premieres in two other cities. The nonprofit, founded by Alfred Lacks Carter, offers transitional housing for individuals released from incarceration. Carter introduced Tony Baysmore, a representative of Baltimore County Executive Kevin Kamenetz, who announced the renaming of one of Turner Station’s streets as Henrietta Lacks Way.

“People had other things they could have been doing,” said Alfred Lacks Carter. “But they came out to learn about a powerful woman who was one of their neighbors.” He said he hopes similar efforts will “preserve the richness of Turner Station.” So does lifelong community advocate Courtney Speed, a stalwart community defender, herself a symbol of perseverance.

Speed’s husband, the community’s barber died in 1978. She battled to hold onto the business. She hired barbers, worked as a beautician and raised six sons. They include Joe Speed, a local football star, U.S. Naval Academy graduate, currently the cornerbacks coach at Georgia Tech. All the while, she burnished her reputation as an advocate, docent and spiritual cheerleader for the community whose history is recounted in “From the Meadows to the Point,” a book by Baltimore County historian, Louis Diggs.

A few years back, Speed co-founded the Henrietta Lacks Legacy Group to build social solidarity and pride inside the community and gain support from those outside. Her dream is for a museum, restaurant and celebration room to draw in visitors and employ youth needing mentorship and jobs. She says a focus on historical tourism, springing in part from Lacks’s narrative, could help encourage new owners for some of Turner Station’s 60 unoccupied houses. Some of the community’s 1,300 apartments, row houses and single family homes have been vacant since Hurricane Isabel in 2003 and are being rebuilt with grants from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Others have been left behind in the wake of the steel mill’s implosion and the shutdowns of General Motors, Western Electric and other employers.

Henrietta Lacks isn’t the only person of fame to spend all or part of a life in Turner Station. There’s Yale graduate and retired NFL playmaker Calvin Hill. There’s former U.S. Rep. and President/CEO of the NAACP Kweisi Mfume, attorney and political activist A. Dwight Pettit and others.

But Lack’s life is a metaphor for the men and women in the community that started out with a few cabins built in the 1800s by steelworkers and became a nearly self-contained village with its own doctors, stores, savings and loan, cab company, movie house, service station and club hosting the nation’s top musicians. Turner Station was a treasured place basking in an aura of stability where nearly every family had links to what Speed calls the “four M’s”—manufacturing, the military, the ministry and the medical institutions, where many of the community’s women worked as registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, housekeepers and care givers.

Like Lacks, many workers died young, some from accidents on the job, others from working in toxic environments where chemicals, asbestos and silicates led to forms of cancer as virulent as the one that took her life. The steel mill could never have run a slab of steel without the too often unrecognized work of black workers like the riggers who employed muscle and physics to move gargantuan pieces of equipment into place. Anonymous. Unheralded. Just like Lacks.

“In the barbershop, we heard stories of hot, hot, jobs given to blacks only and workers who were killed on the job,” Speed said in a video produced by University of Maryland, Baltimore County’s “Mill Stories” project.

Speed says she’s disgusted a Family Dollar Store is planned at the “gateway to the historic Turner Station” at the corner of Dundalk Avenue and Main Street. To build the store, the owners took down a historic building. “It hurts my heart,” she says. Turner Station residents, says Speed, only found out about the store, being built by a Florida-based developer, in a story in the Dundalk Eagle. Local pastors and other residents, she says are prepared to boycott the store. “ Our slogan will be, ‘We won’t buy. Let it die,’ says Speed who says residents want construction stopped and the community involved in how the lot will be developed.

Eric Smith and other younger folks are there to help. Two weeks ago, Smith attended a program sponsored by the Henrietta Lacks Legacy Group to commemorate Turner Station’s steelworkers. The event featured Tony Buba, a well-known Pittsburgh filmmaker who, in 1996, joined with United Steelworkers activist Ray Henderson, to produce the celebrated documentary, Struggles in Steel, a poignant window into the courage of workers who simultaneously challenged discrimination and economic injustice.

Smith, the son and grandson of workers at the long ago abandoned former Bethlehem Sparrows Point Shipyard, was raised in Turner Station. He had left for North and South Carolina, but returned to help his aging relatives, finding work in a in the paint department at the U.S. Coast Guard in nearby Curtis Bay. He said he wants to help honor the legacy of his parents and Henrietta Lacks, too, by keeping Turner Station alive and thriving.

Speed is inspired by support coming from the academic, medical and religious communities. Jean Walker from the nearby Dundalk, Patapsco Neck Historical Society and Museum attended the film showing. She said a few copies of Skloot’s book in different languages are in demand as authors and others visit the museum to research the area’s history. .

Prince Anna Thomas and her husband Jim, a retired military intelligence officer, drove from Severn, Md. They hadn’t been back to the area since Jim was stationed at Fort Holabird in 1970, before his transfer to Fort Mead. They saw an announcement for the event on a church e-mail blast. Jim Thomas hands out cards carrying his phone number and e-mail address saying, “Retired-But Useful. Helping others gives me Great joy!”

The volunteer just might soon be getting a call or e-mail from Courtney Speed and the Henrietta Lacks Legacy Group. It’s all about immortality.

The Henrietta Lacks Legacy group is accepting tax-deductible donations. Funds are needed to finance a Henrietta Lacks exhibit in Baltimore’s National Great Blacks in Wax Museum and to hire a planner and architect to begin drawings for a museum, restaurant and celebration room in Turner Station. Donations can be sent to the Henrietta Lacks Legacy Group, P.O. Box 21882, Turner Station Md. 21222.

Volunteers are also needed to help Turner Station’s elders with home repairs. Volunteers gather on Saturdays between 9:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. at Speed’s Grocery Center-201 Main St., Turner Station, Md. 21222. For more information, call Servant Courtney Speed at 410-340-4888.

Len Shindel began working at Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point Plant in 1973, where he was a union activist and elected representative in local unions of the United Steelworkers, frequently publishing newsletters about issues confronting his co-workers. His nonfiction and poetry have been published in the “Other Voices” section of the Baltimore Evening Sun, The Pearl, The Mill Hunk Herald, Pig Iron, Labor Notes and other publications. After leaving Sparrows Point in 2002, Shindel, a father of three and grandfather of seven, began working as a communication specialist for an international union based in Washington, D.C. The International Labor Communications Association frequently rewarded his writing. He retired in 2016. Today he enjoys writing, cross-country skiing, kayaking, hiking, fly-fishing, and fighting for a more peaceful, sustainable and safe world for his grandchildren and their generation. Shindel is currently working on a book about the Garrett County Roads Workers Strike of 1970 www.garrettroadstrike.com.