Labor Day, 2016-A Survivor’s Story

It’s the only U.S. holiday dedicated solely to workers. And since there’s no parade in my town, this should be an occasion for a guy who worked in a steel mill and still loves unions—who enjoys the fruits of his collectively-bargained pension—to kick back on his deck with a fine brew and reminisce about the people, predicaments and pride commemorated on Labor Day.

Problem is, see, I’m a writer who still reads newspapers. And, even before Labor Day rolls in, I get apprehensive. I brace myself against the inevitable editorials that will declare U.S. unions and manufacturing to be dead as a rotary phone.

In many cases, business reporters who don’t know squat about unions or manufacturing write these editorials that will ooze across social media.

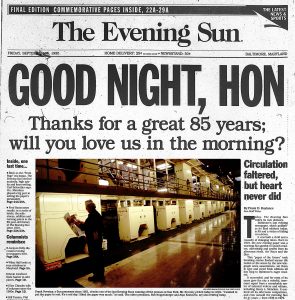

Gone are almost all reporters on “labor beats.” Gone are papers like Baltimore’s The Evening Sun that even invited guys like me, who wore hardhats and steel-toed boots, to pen a column now and then.

Yesterday’s writers spent most of their Labor Day columns celebrating workers. Period.

In 1989 the venerated writer, Studs Terkel, employed his characteristic wit and satire to recall labor’s heroes in a video about the worker’s holiday.

The same year, Chicago’s working-class wordsmith, Mike Royko, penned a Labor Day column, “Hard Labor is More than Brawn.” Royko tersely listed all the jobs he had and what they meant to him. No statistics on union density. No prognosticating on the future of manufacturing. Just a wheelbarrow full of respect for regular folks who plant trees, move furniture and even sell grave stones for a living.

To be truthful, I have no problem with Labor Day columns that accurately analyze the shape of organized labor or manufacturing. And, yes, the workplace and our work force have changed drastically since the Baltimore Evening Sun folded. And, for sure, I need to grow out of my nostalgia.

But sometimes on Labor Day writers just have to say thanks to a solid worker. And Rich Houston, one of my former co-workers, who lost his job when the former Bethlehem Steel plant shut down in 2012, is the just the kind of guy Studs Terkel or Mike Royko would have wanted to talk to.

If manufacturing is dead, Rich Houston hasn’t gotten the message. He works midnight shifts at National Gypsum making sure the edges of freshly born drywall sheets stay on the straight and narrow.

Staying on the straight and narrow kind of describes Rich, a member of Teamsters Local 570. Despite the long shifts, he regularly lifts weights and dances to house music. In fact, coming of age in the Catonsville community of Ellicott Mills at the end of the disco era, Rich has become something of an expert on the history of the genre from its birth in Chicago in the 1980s to today’s music scene at Club 347 on Calvert St. and Pulse Nightclub on Saratoga.

“I’ve never been in any trouble,” he says. “I was the kid with perfect attendance. I’m still that way. You never have to get me up to do what I need to do.”

After school days at Woodlawn High, Houston worked at High’s, Little Caesars Pizza, Montgomery Wards and Toys R Us.

He expected to graduate into a career in law enforcement. His mother, who worked in a juvenile detention facility, had died at age 23 when he was only 19-months-old. His great aunt, an elementary school principal, and her daughter, a parole and probation officer raised him.

Houston took classes in criminal justice at Community College of Baltimore County, Catonsville and then transferred to Morgan State University where he majored in political science.

Houston’s uncle worked at Charles Hickey School for Boys, a detention center. He helped Rich follow the path of the mother he never knew, but whose striking image he posts on Facebook every Mother’s Day. Houston became a youth worker at Hickey, supervising boys from 11 to 16.

“The inmates were only 10 years younger than I was. It was a mixed bag. It was hard to get respect. But I could relate to their dress styles, their music and the way they thought about stuff,” he says.

In 1997, after his wife, Donja, went to work for Burns Security at Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point Plant, Houston followed, taking the entry test to work inside the steel mill.

“I had heard about Bethlehem Steel. I heard they had a strong union and you could end up making good money and be a guy who drove a pickup truck, living next door to guy who works downtown in an office,” says Houston.

At Sparrows Point, Rich was assigned to the plant’s Hot Dip Coating Line, built in 1993, where 45,000-pound steel coils zipped through a pot of molten zinc and then through towers at 620-feet-per-minute. The high-quality steel would later become the smooth outside shells of washing machines and hot water heaters.

“Overall, we all got along great,” Houston says of his co-workers. Despite their cohesiveness, workers, who had transferred from other departments, often clustered around those with similar experiences in the plant. Houston learned all of the jobs on the line and, later, employed his skills understanding the range of his co-workers’ experiences as a shift manager.

One of the things he learned was to honor the union’s contract. “Most managers respected the union and the members’ knowledge of fair work practices. Most of them tried to avoid conflicts. We worked together. It was a beautiful thing,” says Houston.

“We had a highly talented, well-trained crew,” says Houston. “Guys could show up on the job and, just by listening to the mill, know what they needed to do.”

Bethlehem Steel filed for bankruptcy in 2001. The aging plant, facing intense global competition, saw a succession of new owners. But Houston, like so many of his co-workers, never expected that all steel production would cease on the 3,200-acre site.

RG Steel, the plant’s final owner, declared bankruptcy in 2012 as costs of raw materials rose and steel prices fell. The federal government sued the owner of the plant’s holding company, Ira Rennert, a former junk bond trader, who lives in a $248 million mega-mansion in the Hamptons, for trying to escape $70 million in pension obligations to employees. Rennert settled. The USW won what it could for its members in bankruptcy court. The plant’s assets were sold to a salvage firm and later demolished.

Houston applied for federal trade adjustment assistance. He enrolled in Community College of Baltimore County Essex and received certification as an emergency medical technician. He applied for jobs with private ambulance firms. He was disappointed with the pay and benefits.

In 2013, Houston returned to the manufacturing sector, landing a job at Crown, Cork and Seal in Essex, Md., in a plant making cans for ConAgra Foods, particularly the iconic brand, Chef Boyardee ravioli. As a line forklift driver, he moved pallets of cans, 22 rows high.

“I was in a new local union of the United Steelworkers,” says Houston. “But a lot of folks didn’t seem to know the agreement. I spent a lot of time reading and understanding our rights.” When the local’s presidency opened up, Houston was appointed to fill the job. Then he ran and was elected. “It took a lot of time away from my family. But I just loved being able to serve as a representative and help people who had trouble standing up for themselves,” he says.

Then the boom fell again. One day before a new three-year collective bargaining agreement was due to begin; the company announced the plant would be shutting down. ConAgra moved most of its orders to a newly built plant in South Carolina owned by Luxembourg-based Ardaugh Group. Only three of Ardaugh’s seven U.S. food-can manufacturing plants are unionized.

Houston threw himself into “effects” bargaining, advocating for severance packages and the continuation of health care benefits for his co-workers.

“After Sparrows Point, I was desensitized to the trauma of a plant shutdown,” he says. “You have to learn how to mentally deal with it,” says Houston.

And, like at Sparrows Point, despite their lives being upturned, says Houston, “Crown, Cork and Seal’s people, including some who came from another shut down plant, did their jobs until the doors closed. There was no stealing, no slacking off.” There still isn’t as Houston and many of his co-workers produce quality drywall at National Gypsum.

Houston, who has two daughters, aged 21 and 16, is still advocating for his co-workers and looking to get more involved in his new union.

“The plant manager told us at a safety meeting he heard workers at Sparrows Point didn’t work hard,” says Houston.

“I told him that’s something you hear in a bar or restaurant. But it’s just not true. We knew what we were doing and made our jobs look easy, just like doctors or other professionals do. Lazy people don’t work around the clock all their lives and produce tons of steel.”

“Look at me,” Houston told the manager. Am I lazy?”

Rich Houston’s question needs to be answered this Labor Day, not just by his plant manager, but by anyone who blames hard-working men and women just like Rich, and their unions, for the tragic decline of our nation’s industrial base.

Len Shindel began working at Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point Plant in 1973, where he was a union activist and elected representative in local unions of the United Steelworkers, frequently publishing newsletters about issues confronting his co-workers. His nonfiction and poetry have been published in the “Other Voices” section of the Baltimore Evening Sun, The Pearl, The Mill Hunk Herald, Pig Iron, Labor Notes and other publications. After leaving Sparrows Point in 2002, Shindel, a father of three and grandfather of seven, began working as a communication specialist for an international union based in Washington, D.C. The International Labor Communications Association frequently rewarded his writing. He retired in 2016. Today he enjoys writing, cross-country skiing, kayaking, hiking, fly-fishing, and fighting for a more peaceful, sustainable and safe world for his grandchildren and their generation. Shindel is currently working on a book about the Garrett County Roads Workers Strike of 1970 www.garrettroadstrike.com.