Edgar Allan Poe’s Warnings Against Slavery

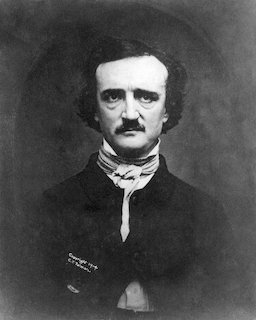

Image by WikiImages from Pixabay

‘The utter impossibility of any one’s soul feeling itself inferior to another’

Six years ago I wrote an essay about Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) and his position as a writer in the antebellum USA, ‘Edgar Allan Poe and the Fall of the House: the Tale of the Announced American Apocalypse’ It described the tale ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ (1839) as an allegory about a deeply divided USA, with a sick and depressed Roderick Usher as a metaphor for the northern states and the severe economic and monetary crisis (‘The Great Panic of 1835’), and the chronically diseased Madeline Usher as a metaphor for the southern states and slavery.

From later research, I concluded that the sinister and exited family doctor and his predecessors in this tale, who were unable to cure Madeline’s chronic problem, are metaphors for Martin van Buren (1782-1862), the 8th President of the USA (1837-1841) and five of his predecessors, who were all slaveholders.

According to most Poe scholars, Poe was a racist and pro-slavery sympathizer, for which they point at tales like ‘Metzengerstein’ (1832), ‘The Black Cat’ (1843), and the novel ‘Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket’ (1838).

However, I think that in Poe’s work one must distinguish between his observations of the society in which he lived and his opinion about it. ‘Usher’ contains both aspects and it even gives a frighteningly accurate description of the course of events that lead to the Civil War. This tale, probably Poe’s most famous one, leaves no doubt that he saw slavery as an evil that would cause a bloody conflict between the northern and southern states. But how did he arrive at this prophecy?

As a toddler of almost three years old, the orphaned Edgar Poe was informally adopted in 1811 by the childless and wealthy merchant John Allan and his wife Frances Keeling Valentine-Allan of Richmond (VA). Out of gratitude Poe later added their family name to his own, although he was never formally adopted. (After his beloved foster mother died he even severed his relation with John Allan, but kept the name).

Richmond was a center of the slave trade and the Allan household had slaves, so young Edgar grew up in an environment where slavery was a fact of life. And since the Allan’s had a black nanny to take care of the little boy, an intimate and tender relationship with a black woman must have been one of his first conscious memories (according to the legend that nanny’s name was Judith).

It is a fact that white children and a black nanny can develop deep emotional relations that last their entire life and easily withstand hardship and misery. A beautiful and moving example is in the movie ‘Gone with the Wind’ (which, by the way, shows the horrors that Poe knew were coming) where ‘Mammy’, an epic and Oscar-winning role by black actress Hattie McDaniel, is the only one who can stand up against and even control the strong-willed and domineering Scarlett O’Hara, who she raised as a child.

In Poe’s later tale ‘The Black Cat’ (1843) – another intriguing and bloody allegory about slavery – this emotional relationship between a child and his nanny is projected on the black cat: “Pluto –this was the cat’s name- was my favorite pet and playmate. I alone fed him, and he attended me wherever I went about the house. It was even with difficulty that I could prevent him from following me through the streets”.

That the black cat is named Pluto –the god of the underworld and the lost souls- is an indication of later doom, because also in this tale the narrator alienates himself from his wife and finally kills her; a process in which the black cat plays a prominent role. And it is the cat who eventually betrays his former master to the police, ensuring his death penalty. If we take the black cat as a metaphor for slavery, this tale depicts Poe’s changing and fluctuating attitude towards slavery during his life, from love to alienation to hatred. And also here the deepening North-South schism over slavery is visible in the changing and different attitudes of the narrator and his wife towards the cat.

Almost simultaneously with the ‘Black Cat’ Poe wrote the tale ‘The Gold Bug’ (1843), in which ‘Jupiter’, a manumitted black man, is the loyal companion and protector of his former master, whom he brings luck and treasure. In all of Poe’s tales, the words ‘slave’ and ‘slavery’ are only used as metaphors, like a man who is the slave of his love for a woman, or the slave of circumstances beyond control. Black persons in Poe’s tales are free spirits and even rebels against the society in which they live, like the black cook on the ship in Poe’s only novel ‘Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket’. According to some Poe scholars, this rebellious and mutinous cook symbolizes the permanent fear among many slave holders for a slave revolt in the southern states.

In June 1815, when Poe was six years of age, the Allan family moved to England and Scotland, where they stayed for five years and where young Poe attended elementary school, even for some time in a boarding school (an experience that he later used for his tale ‘William Wilson’). These five years in England and his excellent education there had a profound effect on young Edgar, which is reflected in much of his later work (See https://baltimorepostexaminer.com/edgar-allan-poe-londons-claim-on-baltimores-greatest-poet/2015/06/25 ).

One may assume that Poe’s gradually changing attitude towards slavery, from favorable to hatred – as depicted in ‘The Black Cat’– started during his stay in England. Already in 1807 the British Parliament had passed an act to abolish the slave trade in the British Empire and slavery was not supported in England itself. Anyway, slavery was a topic of much discussion and young Edgar certainly witnessed discussions about slavery or even participated in such discussions with his teachers and other pupils. So when he returned from England to Richmond in 1820, his opinion on slavery and thus his view on the American society must have changed for good.

In an earlier essay I have argued that Poe was a ‘marginal’ personality; someone who is never really at home in this world, because he feels that he doesn’t belong there: This was the result of deeply traumatic experiences during his early youth, like the disappearance of his father, the death of his mother, the adoption by strangers, the loss of a beloved nanny, the elementary education in alien England. Marginal people have no emotional attachment to the world and its issues, but they are keen and sharp and merciless observers. It is thus possible that Poe had no deep feelings pro or against slavery in itself, but he was very aware that it was a fatal and ugly flaw that would destroy the American society. And that is why slavery had to disappear; why this deadly issue had to be resolved at a higher level.

And that was finally done in his last and greatest work, the cosmogony ‘Eureka. An Essay on the Material and Spiritual Universe’ (1848). In the last pages of this essay – the spiritual part- he declares his vision on perfect equality of all human souls:

The utter impossibility of any one’s soul feeling itself inferior to another; the intense, overwhelming dissatisfaction and rebellion at the thought; these […] are, to my mind at least, a species of proof far surpassing what Man terms demonstration, that no soul is inferior to another; that nothing is, or can be, superior to anyone soul; that each soul is, in part, its own God – its own Creator.

After Eureka was published Poe wrote: “I have no desire to live since I have done Eureka. I could accomplish nothing more.”

He had finally reached the ideal world that he had created for himself, to live in forever.

Feature Image by Clker-Free-Vector-Images from Pixabay

René van Slooten is a leading ‘Poe researcher’, who theorizes that Poe’s final treatise, ‘Eureka’, a response to the philosophical and religious questions of his time, was a forerunner to Einstein’s theory of relativity. He was born in 1944 in The Netherlands. He studied chemical engineering and science history and worked in the food industry in Europe, Africa and Asia.The past years he works in the production of bio-fuels from organic waste materials, especially in developing countries. His interest in Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘Eureka’ started in 1982, when he found an antiquarian edition and read the scientific and philosophical ideas that were unheard of in 1848. He became a member of the international ‘Edgar Allan Poe Studies Association’ and his first article about ‘Eureka’ appeared in 1986 in a major Dutch magazine. Since then he published numerous articles, essays and letters on Poe and ‘Eureka’ in Dutch magazines and newspapers, but also in the international magazines ‘Nature’, ‘NewScientist’ and TIME. He published the first Dutch ‘Eureka’ translation (2003) and presented two papers on ‘Eureka’ at the international Poe conferences in Baltimore (2002) and Philadelphia (2010). His main interest in ‘Eureka’ is its history and acceptance in Europe and its influence on philosophy and science during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.