Pearl Harbor survivor recalls nixed warning on ‘Day of Infamy’

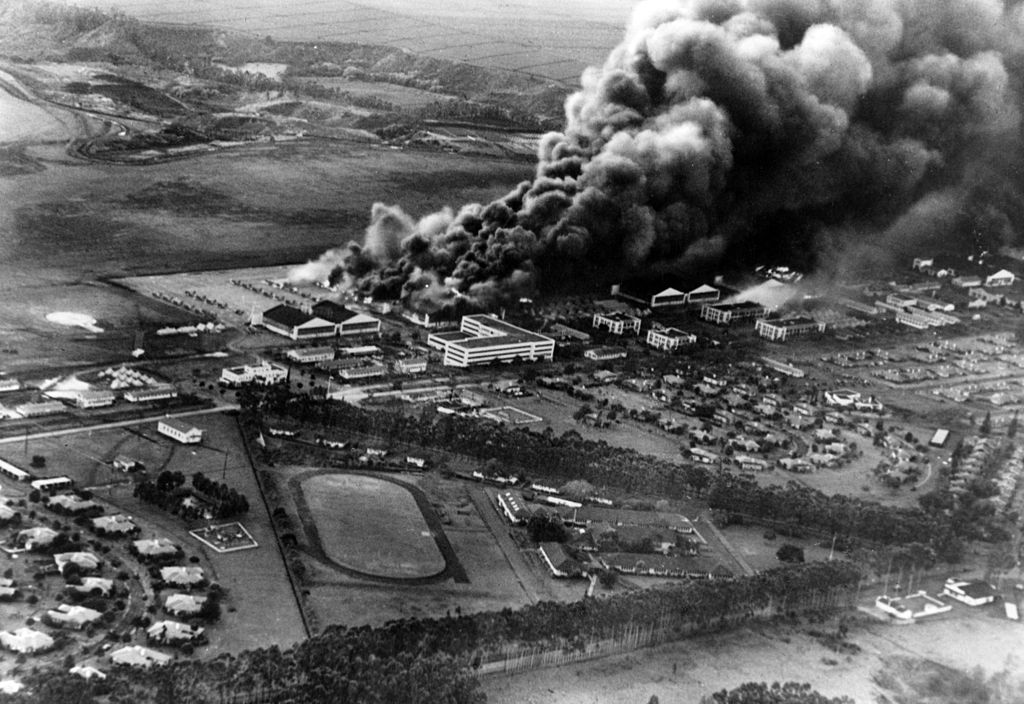

A Japanese aircrew captured this image of planes and hangars burning at Wheeler Field during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, 7 December 1941.

Seventy-five years ago today, the American military installations in and around Pearl Harbor were ruthlessly attacked by air and naval forces of the Empire of Japan. The December 7 attack – which President Roosevelt would describe as “A date which will live in infamy” – came as a surprise to most Americans. But there were two soldiers in Hawaii that morning who saw the waves of airplanes coming on the oscillator screen of a then-novel device which was simply called radar.

S/Sgt Richard G. “Dick” Schimmel was on the ground at Fort Shafter (just east of Pearl Harbor), when the Japanese launched their assault. By virtue of his assignment to the Aircraft Warning Service, he was the fifth person to know the attack was about to happen. Tragically, an alarming communiqué sent by the two soldiers at the radar station was summarily dismissed.

The Baltimore Post-Examiner met Dick Schimmel last summer at the Mid-Atlantic Air Museum World War II Weekend. Now 95 years young, Schimmel recalls the events leading up to the attack as if they happened yesterday.

“I enlisted in the Army on August 28, 1940. We were sent to Hawaii in December of 1940 and received our first radar device in the middle of 1941. We assembled it – even though we didn’t know what to do with it – and learned how to use it. We also helped to set up the Information Center at Fort Shafter, where we could plot the planes on a big table. That’s where I worked most of the time.”

Schimmel worked primarily as a plotter and switchboard operator while stationed at Fort Shafter. On the evening of December 6, 1941, he was relieved from his post at 6:00 PM by his tent mate, Private Joseph McDonald. Rather than taking in a relaxing night in neighboring Honolulu, Schimmel stuck around the base to unwind – eased perhaps by the knowledge that a week-long high alert had earlier been canceled. As Schimmel slept in that Sunday morning, a historic drama was steadily unfolding just steps away at the Information Center.

Private George Elliot, one of the two soldiers manning Fort Shafter’s Opana Radar Station on the northern tip of Oahu, noticed a large mass of aircraft on his radar’s oscilloscope. Unsure of what he was witnessing, Elliott turned to his more experienced mentor, Private Joseph L. Lockard. Schimmel said that, with the alert being canceled, Elliott and Lockard had ventured to the Opana Station to get a little extra practice with the truck-mounted mobile radar equipment. For a few short moments, the two men puzzled over the oscilloscope. After checking to make sure the equipment was in order, a decision was made to call the Information Center at Fort Shafter where Elliott spoke with Private McDonald.

McDonald jotted down Elliott’s excited report and relayed the message to Lieutenant Kermit Tyler – the sole officer on duty at the Information Station that Sunday morning. Everyone else, it seems, had been dismissed to go to breakfast. Tyler surmised that the blips on the radar were, “not anything to worry about”. A return call by McDonald to Lockard only served to heighten McDonald’s concern. Lockard said he had never seen so many planes before. Failing to get Tyler to act on the hand-written message, McDonald insisted Tyler speak directly with Lockard. In that brief conversation, Tyler never asked Lockard to quantify the number of planes he was seeing on the scope but rather informed the anxious observer that a flight of 12 Army B-17 bombers from the mainland was due to arrive in Hawaii sometime that morning. Again, Tyler advised the men at Opana not to worry.

Tyler’s conversation with Lockard would have happened at around 7:30 AM. At 7:55 AM, all hell broke loose.

McDonald was relieved of his duty at 7:40 AM that morning. He went back to his tent and awoke the still-sleeping Schimmel.

“Joe said to me, ‘Hey Schim, the Japs are coming.’ This was before the attack, so I thought he was joking. A few minutes later, we started to hear the bombing.

“I figured from my conversation with Joe, when he woke me up that morning, that I was the fifth man to know about incoming Japanese aircraft. Once the bombing started, everyone was called back to the Information Station. That’s when I found the message Joe had taken over the phone from Elliott, balled up in a trash can.”

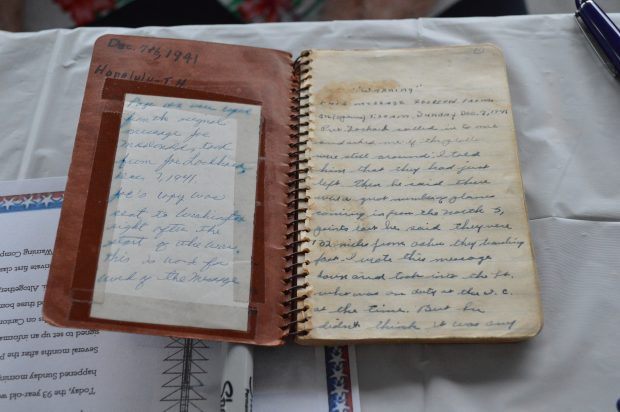

McDonald’s hand-written message would eventually be secured and packed away to Washington, D.C. But not before Schimmel copied it word-for-word in a spiral-bound notebook. Schimmel showed us the yellowed notebook, with the date “December 7, 1941” clearly visible in blue fountain ink. Also clearly visible were the words, “a great number of planes coming in from the north.”

Schimmel stayed in the Army for the duration of the war, spending some 56 months overseas before settling down in Allentown, Pennsylvania. He would also live through three more Japanese bombings while stationed in the Pacific on Canton Island where he came accross “the biggest rats” he had ever seen.

Schimmel said the message snafu bothered McDonald for the rest of his life, but in the end, there was really nothing more he could have done. “If we had gotten more of the planes from Wheeler (Field) into the air, maybe it would have helped, but Joe could not go over Tyler’s head.”

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”