Former steelworkers divided over NFL protests

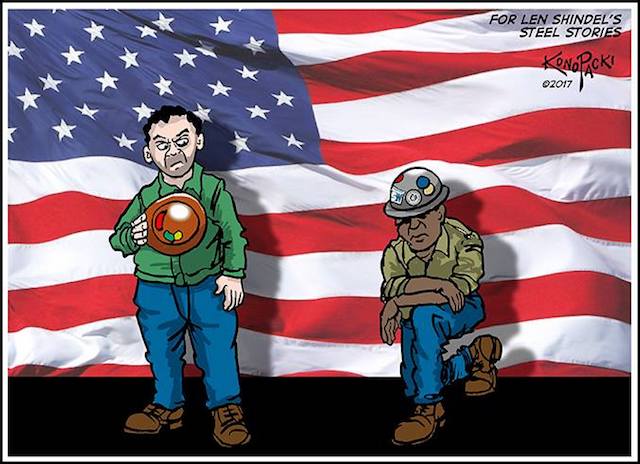

Illustration by Mike Konopacki

Since President Trump called protesting NFL players “sons of bitches,” who should be fired on September 22, I have been reading dozens of Facebook posts on the controversy from my former co-workers at the now shutdown Bethlehem Steel mill at Sparrows Point, Md.

It seems more than half of my white co-workers posting about the controversy oppose athletes who “take knees” during the national anthem or NFL owners who grant them the right to that avenue of protest. Some are calling for an NFL boycott or boycotts of companies that advertise during games.

They say the protests, which began when former S.F. 49er Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem to protest the killings of black Americans by white police officers, dishonor our nation and members of the military.

Conversely, it seems the vast majority of my black co-workers posting on Facebook support the right of players to protest during the Star Spangled Banner.

Among co-workers in both groups who support the players’ rights to protest, some say they would stand for the anthem and find other ways to express themselves, were they in the athletes’ cleats. A few others argued for more civility between folks on both sides of the issue.

I know most of these Facebook friends and former co-workers well. Having served as a United Steelworkers representative for more than two decades after my hiring in 1973, I know they generally respected and supported each other on the job,

I wish I could express alarm at the racial divide among these friends. These are men and women who worked closely together for decades of their lives, spending weekends and holidays on the job, working around the clock, sharing joys and sorrows, defeats and victories, dreams and nightmares and mourning co-workers who were killed or maimed at work. Many of their children go to the same high schools or work on the same jobs. Some married. I see beautiful photos on Facebook of co-workers celebrating birthdays with their multi-racial grandchildren.

Despite these deep veins of commonality, the chasm on politics and race between my co-workers, amplified on social media, was fiery as a blast furnace during the build-up to the 2016 Presidential Election.

I am still astounded when I see co-workers call hard-working athletes who collectively bargain for their earnings “spoiled” millionaires who claim false oppression and shouldn’t bring their politics to the field, even as some of them worship a reality TV star and son of privilege who launched his political career questioning the citizenship of the first African-American president.

In our polarized discourse, many of us miss the poignant words of military veterans who say they fought for the right of people to express themselves and ask that their service not be used to impugn the patriotism of those who take knees on the flag, whether they are protesting police killings or taking issue with the president’s attack on those who do.

I was raised in the 50s and 60s to believe each generation builds upon the wisdom of its predecessors. Coming from a Jewish family, I was taught to be attentive to the ostracizing of people who stand up for fairness in society. I always found much agreement on that aspiration from my co-workers, who were predominantly white Catholics and black Protestants.

I’m from Connecticut. We had no NFL team and I never adopted one. I always enjoyed the comradely combat between Steelers and Ravens fans on the job. But this rivalry, bursting across the gridiron, over politics, culture and race, is as disturbing to me as the Monday morning ragging was humorous. In rejecting the protests of black athletes, I believe my friends are falling into the same self-defeating trap as too many of those who preceded them at Sparrows Point and rejected the legitimacy of protest against discrimination in their own backyards.

In 1974, one year after I was hired at Sparrows Point, Bethlehem Steel and other major steel producers entered into a consent decree between the union and the federal government that altered seniority systems in the industry. The decree was the product of years of protests and lawsuits by black workers. For decades, black workers had been hired into the hottest, dirtiest, most dangerous departments in the mills. Even in cases where they were permitted to transfer to cleaner, higher paying “white man’s jobs,” they were forced to stay at the bottom of the seniority ladder, no matter how much time they had accrued in the plant.

The consent decree abolished the “unit seniority” system. Now workers who transferred to new departments could use their plant service to move up to better jobs. The decree also set goals on the hiring of black workers into trade and craft departments that had been all or overwhelmingly white due to blatant bias. The decree offered back pay to black workers for past discrimination under the condition they waive all rights to future legal action.

All hell broke lose with the signing of the consent decree. I remember passing a bulletin board just outside the women’s bathroom that only a few years before had been the “colored” facility. A goldenrod flyer announced a meeting of the Ku Klux Klan in Rising Sun Md.

A group of white workers filed a lawsuit against the decree. They claimed the order would “flood the mills” with “unqualified” workers who would drag the company into the ditch. Racial conflict threatened to erupt in fisticuffs on the job. Even some of us who acknowledged historic discrimination advanced the notion the decree “punished” white workers for the sins of the company.

We were proven wrong, very wrong. A wave of technology was eliminating jobs throughout the plant. The technology didn’t discriminate by race. Now the consent decree, the legal document that had been derided for favoring black workers to the detriment of whites, ended up being a lifesaver for tens of thousands of white workers, too. They transferred to other departments and used their plant seniority to move up the ladder in their new departments. Some of the white beneficiaries of the consent decree were the fathers, uncles and grandfathers of my co-workers who now are posting memes on Facebook assailing the “patriotism” of athletes who protest discrimination.

The same year the battle over the consent decree raged, another long-running clash came to a head in Sparrows Point’s coke ovens. The overwhelmingly black department, where coal was baked at high temperatures into coke, a critical component in producing high-carbon steel, had earned a reputation as the hottest, dirtiest sector of the mammoth 3,200-acre plant. For years, black coke oven workers and their allies—organized across the nation—had engaged in advocacy to alleviate unsafe conditions and low pay. Their struggle against workplace toxins and industrial cancer and their advocacy of greater protections from OSHA is recounted in an article “Gateway to Hell” in the Journal of African American History (Winter-Spring 2016).

By 1974, Bethlehem had hired a fair number of whites, some of them Vietnam Veterans, to work in the coke ovens. Led by a black grievance committeeman, Johnny Fair, a few busloads of coke oven workers, black and white, high and low on the seniority ladder, traveled to Washington, D.C. to picket a United Steelworkers conference. They pressed for support from the union hierarchy to clean up their workplace and win greater dignity on the job.

Returning to Baltimore from the picket, they waged a two-day wildcat strike that nearly shut down the entire plant. Their rebellion was successful. The company constructed clean, air-conditioned cooling rooms where coke oven workers could eat their lunches. Incentive pay was increased. The workers won other protections, too, and new respect from Bethlehem Steel management.

Once again, in the most challenging environment within the mills, white workers were benefitting from a decades-long struggle and protests led by their black peers.

Some of my former co-workers, in their 40s and early 50s, who are calling on protesting NFL players to be fired know nothing of those days of struggle in the plant. As a union leader, I take their lack of knowledge of their own history as a personal and institutional failure. Our once-influential union needed to be more engaged in the surrounding community.

We should have formed a team of black and white union members to visit local high schools and bring them the powerful lessons of our struggles over seniority and working conditions. They were timely examples of Dr. King’s truth: “We are tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Some of my peers were part of the protests in the coke ovens or benefited from the provisions of the consent decree. But they, too, see no connection between the issues inside their former workplace and the discrimination players are protesting today.

I expect the arguments over whether players kneeling are honoring or dishonoring our nation’s flag to continue. But even as we argue, President Trump and his party are uprooting or undermining all manner of governmental protections covering the bulk of his supporters—healthcare insurance, job safety, union representation, women’s rights, overtime pay, food quality, credit card fraud etc. Plans are in the works for massive tax cuts for corporations and wealthy individuals.

The profits will be poured into electronic technologies that are predicted to eliminate millions of jobs. What will the 99% rely upon for economic sustenance when municipal and federal budgets are busted?

Maybe some day more of my white co-workers and their children will come to see themselves as beneficiaries of the NFL protests being attacked by President Trump, just as they are the legatees of the struggle against discrimination waged by their black co-workers at Sparrows Point.

Maybe we should take a little time out from our arguing and meme-posting and listen closely and quietly to a hometown hero.

“I wish I could say that racism and prejudice were only distant memories,” said the legendary Baltimore resident, Justice Thurgood Marshall. “We must dissent from the indifference. We must dissent from the apathy. We must dissent from the fear, the hatred and the mistrust…We must dissent because America can do better, because America has no choice but to do better.”

Len Shindel began working at Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point Plant in 1973, where he was a union activist and elected representative in local unions of the United Steelworkers, frequently publishing newsletters about issues confronting his co-workers. His nonfiction and poetry have been published in the “Other Voices” section of the Baltimore Evening Sun, The Pearl, The Mill Hunk Herald, Pig Iron, Labor Notes and other publications. After leaving Sparrows Point in 2002, Shindel, a father of three and grandfather of seven, began working as a communication specialist for an international union based in Washington, D.C. The International Labor Communications Association frequently rewarded his writing. He retired in 2016. Today he enjoys writing, cross-country skiing, kayaking, hiking, fly-fishing, and fighting for a more peaceful, sustainable and safe world for his grandchildren and their generation. Shindel is currently working on a book about the Garrett County Roads Workers Strike of 1970 www.garrettroadstrike.com.