Tortured for Christ: Film Recounts Persecution in Communist Romania

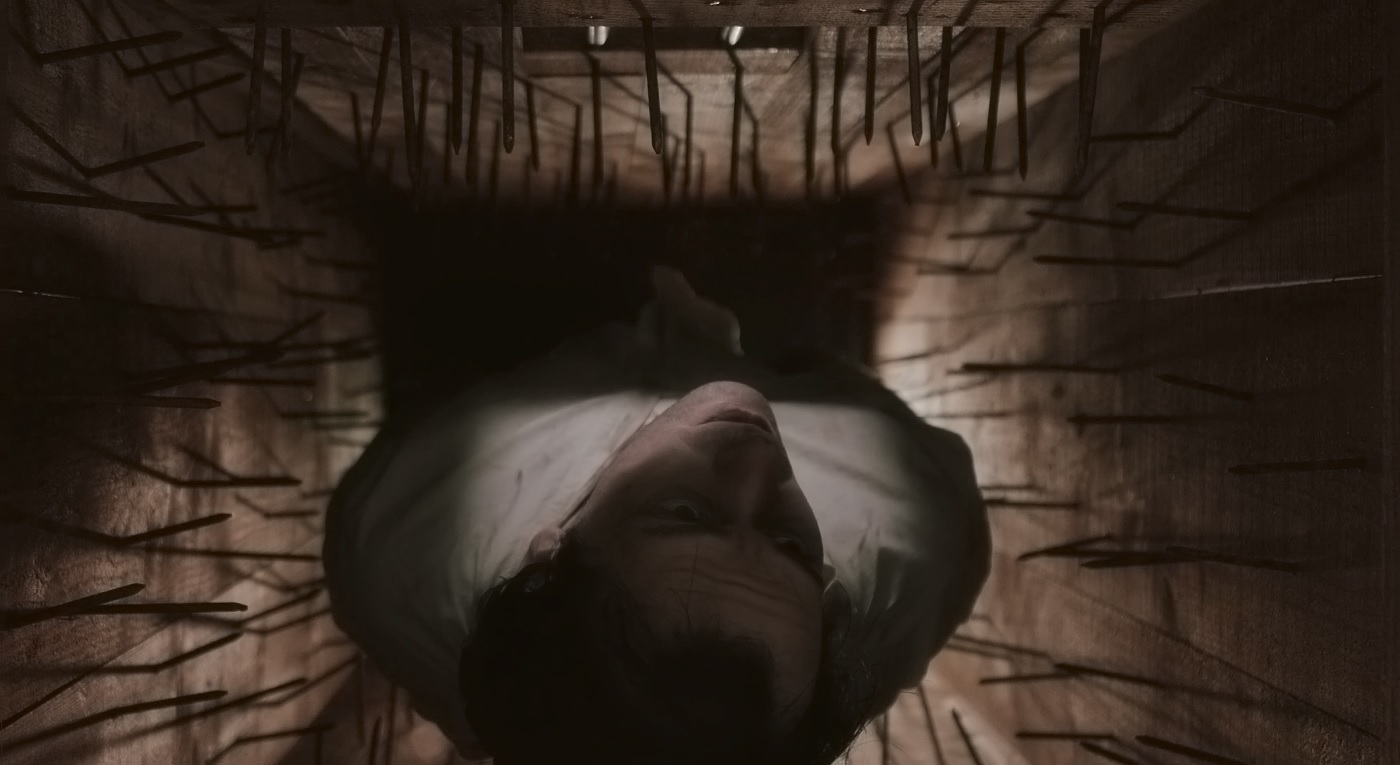

Richard Wurmbrand (Emil Mandanac) is left to consider his fate inside a nail-embedded box in the docu-drama Tortured for Christ.

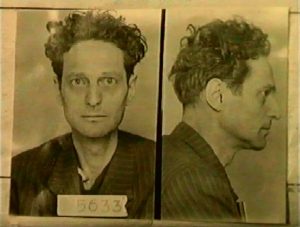

We all have particular dates on the calendar which bring a rush of memories to mind. For the late Richard Wurmbrand, February 29, 1948, was one such day. That was the date Wurmbrand was blindfolded and spirited off a street in broad daylight, driven to a penal facility in another city, questioned for hours by the secret police without legal counsel present, and then finally thrown into a subterranean prison cell. His crime? Pastor Wurmbrand had dared to defy the Soviet-backed communist government in Romania by preaching the gospel of Christ.

Wurmbrand would somehow survive a total of 14 years in prison, before being ransomed out of Romania in December 1965. Shortly thereafter, he wrote his best-selling book, Tortured for Christ. In October 1967, Richard and his wife, Sabina (who had also been imprisoned for three years in the early 1950s) founded a worldwide ministry that would later be known as The Voice of the Martyrs. Their aim was to spotlight the plight of Christians living under repressive regimes.

Wurmbrand’s gripping book is the subject of a 2018 dramatized documentary. The film – also titled Tortured for Christ – has had limited showings since its release. However, it garnered a worldwide audience via the internet last weekend to commemorate that inauspicious February 29 date. Filmed entirely in Romania – including inside the very prison where Wurmbrand was confined – this powerful story is told in English, Romanian and Russian (with English subtitles), to immerse the audience into the authenticity of the story.

It is not a tale for the faint of heart.

The story opens with Richard (Emil Mandanac) and Sabina (Raluca Botez) attending a congress where Joseph Stalin is recognized as a patron of the Church. Underlining the congress is one stark reality: church leaders could enter into the service of the Russians, or they could go to jail. Realizing the ramifications of such a move, Wurmbrand asks to address the congress. His speech stirs the audience, but it makes him a marked man in the eyes of the oppressive overlords.

“The Communists knew that faith in God was the only resistance left,” notes Wurmbrand. And so that faith would be put on trial.

Wurmbrand (a Jewish convert and ordained Lutheran minister) would continue with his parish duties, but the meat of his work would necessarily be driven underground. That work not only included clandestine Bible studies and meetings, where he could baptize new believers, but also occasions where he and others would share their faith with the occupying Russian soldiers.

“We loved the Russians so much, we risked everything to bring them the Gospel. They were meeting an entirely new kind of Christianity – the Christianity of the underground church.”

The price for this boldness would land the earnest pastor in prison. But even in his confinement, Wurmbrand found unexpected solace in his Leap Year arrest:

“I had discovered 366 verses in the Bible which instruct us not to fear. One for each day of the year – and even one for leap year. I remember the verse for this date: Psalm 56:3

“What time I am afraid, I will trust in thee.”

The Wurmbrands personal story is punctuated by several short vignettes showing what a number of their fellow Christians had to endure.

In one scene, a group of inmates working in a slave labor camp know for a fact that it is Saturday, because that was the day the guards always beat one fellow inmate – a Seventh Day Adventist.

“I don’t like to speak much about the horrific suffering,” remarks Wurmbrand. “When I speak of it, I don’t sleep at night.”

Even from the get-go, Wurmbrand’s interrogator sums up what communists had in store:

“We’re not murderers like the Nazis,” the commandant blithely says. “We want you to live – and suffer.”

“Communism had stripped them of any form of humanity, and they sank into unthinkable depths of cruelty,” recalled Wurmbrand. “Darkness ruled their every action, and only God’s love could restore them.”

But could God’s love preserve Wurmbrand?

“For three years, I was in solitary confinement. I had only my thoughts for company, but I had God. I remembered what the martyr Savonarola wrote. He said, ‘There are two kinds of Christians: Those who sincerely believe in God and those that, just as sincerely, believe that they believe in God.’ Did I believe in God? Now the test had come.”

Wurmbrand would find comfort in solitary confinement, by composing hundreds of sermons which he would then deliver to his cold, prison walls. But he also found comfort, once he was moved to a communal hospital cell, in a way which turned Savonarola’s quote around:

“I saw many men die in that room. And here is a remarkable fact. Not one died an Atheist. None of them died without making his peace with God and man. Many entered Room 4 as firmly convinced unbelievers, but I saw their unbelief collapse always in the face of death. Just as many men think themselves religious but they are not, so some think they are Atheist without being so.”

Tortured for Christ is one of the most difficult films this critic has ever watched – difficult not only because of the brutality displayed on the screen – but because the torment portrayed there-in is true. Wurmbrand brought that reality to the U.S. Senate’s Internal Security Subcommittee in 1966 – stripping to the waist to show the scars of his ordeal.

Those who met him in later years said Wurmbrand did not wear shoes, because his feet were too misshapen from the persistent beatings.

One online reviewer aptly observes that this is a film that should get a much larger audience and not be relegated to screenings in church basements.

And with good reason.

Tortured for Christ is both carefully directed and very well-acted. This is especially true, not only with the aforementioned leads, but also with supporting players like Adrian Anghel as the sadistic torturer, Major Brinzaru. Costuming and locations are faithful to the era, while the cinematography perfectly sets the mood. It is also tight. At 77 minutes, there isn’t time for wasted motion – hence, the action moves purposefully through some very difficult scenes. But even with the unsettling nature of the subject, the viewer is left in the end to marvel at the unshakable hope and love so many held onto in the face of man’s inhumanity to man.

Tortured for Christ is Richard Wurmbrand’s shocking account of the onerous cross he bore under the hellish hand of Atheistic Communism. It’s a story with its roots in the Roman Empire and the persecution of a peculiar people – one which continues in “civilized” nations around the world today.

“There were thousands (of other people like me) – each one had a story.”

* * * * *

Editor’s note: This is the 33rd part of an ongoing series which looks at the places and people that make up the rich history and diverse nature of spirituality, belief and observance in Baltimore and beyond. Read the series here.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”

Thanks Tony for reaching out and sharing this.

It is a need to see. I will share this with my circle of people. By what you have shared everyone should see the movie or read the book. Thanks again Brother!

Love , Gary