Baltimore Catholic worker stories inspire

“The Long Loneliness in Baltimore: Stories Along the Way,” by author Brendan Walsh and illustrator Willa Bickham, recounts the couple’s 50 years, living in Southwest Baltimore, nourishing and sustaining Viva House, a soup kitchen and homeless shelter inspired by Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker movement.

“This volume is one of real christian art. And real christian words,” writes David Simon, creator of “The Wire. He adds: “This is the beauty that comes from lives spent in service of real christian ideals in a very real and unchristian place called Baltimore, Maryland.”

Like Simon, I was raised in a Jewish household. But, I, too, was deeply moved by Walsh’s and Bickham’s precious stories of urban struggle, published by Apprentice House, the country’s only campus-based, student–staffed book company at Loyola University, Maryland.

Like Simon, I was raised in a Jewish household. But, I, too, was deeply moved by Walsh’s and Bickham’s precious stories of urban struggle, published by Apprentice House, the country’s only campus-based, student–staffed book company at Loyola University, Maryland.

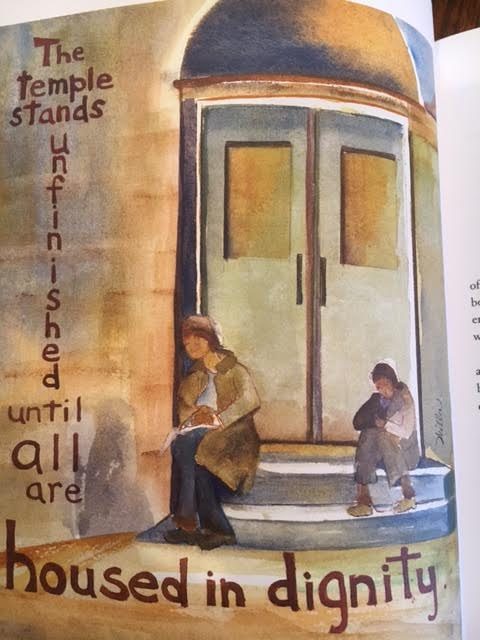

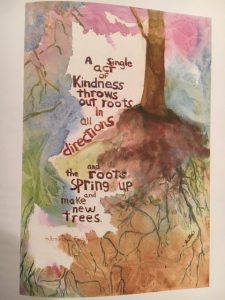

These narratives, poems and pictures bare the couple’s pious, but irreverent and iconoclastic Catholicism, the joy of their service to the suffering, and their lifelong resistance against the forces of greed and militarism inside Baltimore’s Sowebo (Southwest Baltimore) and far beyond.

In the story “Alley of Tears, 2014,” Willa, a former nurse and nun from Chicago, who had just been enjoying time with her three granddaughters, scurries to staunch the bleeding of Oscar Torres, a Mexican immigrant. Torres has just been shot in the head at point blank range near Viva House’s front door. The young man’s body lies adjacent to the Stone of Hope she and Brendan had placed there years before. Despite Willa’s help, the young man bleeds out. The couple prays with his family. But they also raise funds to send his body back to Mexico.

One of Bickham’s watercolors portrays the corner on Mount St., the police department’s ubiquitous blue light—reserved for drug-trafficking corners—bends over young people marching with a sign, saying, “Now.” The pastels portray policemen with billy clubs, a young man doing sit-ups on an incline board at the elementary school across the street, a woman with a bag and cane showing up at a front door, and the Stone of Hope carrying Dr. King’s quote: “We will hew out of the mountain of despair, a stone of HOPE.” Next to the stone, Bickham etches a prominently set, single word, “Enthusiasm.”

In “Snapshots of Sowebo,” a young man stops by Viva House. Willa and Brendan, a former seminarian who came to Baltimore from the Bronx in the 60s, expect a request for some kind of help for “food, clothing, money, water, the phone or filling out some government form.” Instead, the man asks to play their piano. He plays for an hour and a half, then leaves. “John really needed to play the piano,” writes Walsh. “I’ll remember that when they blow up the next public housing units, making even more people homeless. People need bread. People need music too. Life in Sowebo.”

From its inception in 1968, Viva House has offered expansive refuge. The place, where Walsh and Bickham raised their daughter, Kate, welcomes folks down on their luck. But it also draws in comfortably situated volunteers looking to do good. And it has been a rendezvous point for some of the nation’s most celebrated peace activists.

Walsh recounts his involvement with his friends, priests Phil and Daniel Berrigan and the Catonsville Nine who raided the town’s draft board, pouring homemade napalm on Selective Service files, burning them in protest of the Vietnam War. He writes about his arrests at “pray-ins” during tours of the White House, at the Pentagon protesting the U.S. war machine and at City Hall in Baltimore for feeding the homeless.

Some stories carry statistics about Baltimore’s grotesque polarization of wealth, the rise of joblessness and homelessness. But the stories and artwork always return to the people. In his poem, “How ‘bout Dem Os Hon!” Walsh writes: “Meanwhile, the kids on the street not coming home at night. Time on the hand. No work for their hands. Schoolboys carry guns, not books. Metal detectors, no books to read. Libraries a-gone-gone. But, hey how ‘bout dem Os, hon!”

Some stories carry statistics about Baltimore’s grotesque polarization of wealth, the rise of joblessness and homelessness. But the stories and artwork always return to the people. In his poem, “How ‘bout Dem Os Hon!” Walsh writes: “Meanwhile, the kids on the street not coming home at night. Time on the hand. No work for their hands. Schoolboys carry guns, not books. Metal detectors, no books to read. Libraries a-gone-gone. But, hey how ‘bout dem Os, hon!”

Walsh’s commentaries on the pain and suffering and the drug trade that has flourished alongside the Inner Harbor’s gentrification are not unique. But the inimitable people who have come through his front door—some living with his family for years—pack his words with power and authenticity. So do his heroes of resistance, drawn from eclectic quarters: Padraig Pearse, a leader of Ireland’s Easter Uprising of 1916, Malcolm X, the Berrigans and Dr. C. Lee Randol, a Baltimore pediatrician and anti-war activist who made house calls and helped found the Baltimore People’s Free Medical Clinic.

Walsh also expresses his admiration for the truths of writer I.F. Stone, who, he says, expressed the “joy” he and Willa have found in their struggles. “The only kinds of fights worth having are those you’re going to lose,” said Stone. “Because somebody has to fight them and lose and lose and lose until somebody who believes as you do wins.”

Dorothy Day, who wrote a book, “The Long Loneliness” and stayed at Viva House during the trial of the Catonsville Nine, remains the place’s prime inspiration. Walsh recalls how Day, whose influence has spread since her death in 1980—with more Catholic Worker houses being established worldwide—opposed her own canonization. “She did not want her sainthood to blunt her radical critique of [what she called] our filthy rotten, system,” says Walsh, who, with Bickham, isn’t afraid to challenge his own religion’s leadership to root out bias and exclusivity.

He skewers the patrimony of the Catholic Church, denouncing its denial of the priesthood to women as not just immoral, but self-defeating. Opposite his passionate call for opening up the Eucharist, Bickham’s black and brown canvas displays a woman in pain, beside the words: “If a woman is hurtin’, Don’t tell her how to Holler.”

Read this book if you, like Walsh and Bickham, desperately want to see a society “where it is easier to be good.” Read this book if you want some valuable help connecting the dots on Baltimore’s painful past and present. Buy this book to share the dreams of a rock-solid couple, grandparents in their seventies, who don’t take themselves too seriously, but fight everyday for a future worthy of the next generations. Order this book if you need some inspiration to get off your couches to help make it happen.

Len Shindel began working at Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point Plant in 1973, where he was a union activist and elected representative in local unions of the United Steelworkers, frequently publishing newsletters about issues confronting his co-workers. His nonfiction and poetry have been published in the “Other Voices” section of the Baltimore Evening Sun, The Pearl, The Mill Hunk Herald, Pig Iron, Labor Notes and other publications. After leaving Sparrows Point in 2002, Shindel, a father of three and grandfather of seven, began working as a communication specialist for an international union based in Washington, D.C. The International Labor Communications Association frequently rewarded his writing. He retired in 2016. Today he enjoys writing, cross-country skiing, kayaking, hiking, fly-fishing, and fighting for a more peaceful, sustainable and safe world for his grandchildren and their generation. Shindel is currently working on a book about the Garrett County Roads Workers Strike of 1970 www.garrettroadstrike.com.