Art Therapy: Humanity found in the most desolate circumstances

“Coffee house,” a 1944 sketch by Dutch artist Josef Spier — who was interned at the Theresienstadt Ghetto — is on prominent display at Beit Terezin.

On the last Sunday in September — as Puerto Rico’s hurricane catastrophe, North Korea’s nuclear threats and Myanmar’s massacre of Rohingya Muslims dominated world headlines — I immersed myself in tangible reminders of a genocide from the not-too-distant past.

Driving along Highway 4 north from Tel Aviv and accompanied by an art therapist from Baltimore, I visited two Holocaust points of interest for the first time: Beit Terezin just outside Hadera, and the Ghetto Fighters Museum between Akko and Nahariyya.

My art therapist friend, Elizabeth Hlavek, has a clinical practice in Annapolis, where she works mainly with teenagers and young adults struggling with eating disorders and body image concerns. Liz came to Israel in order to gather research toward her doctoral dissertation, which examines artwork created clandestinely during the Holocaust, and how that relates to current art therapy theories and practices.

As part of her culminating doctoral project, Elizabeth is organizing an exhibit of reproductions of these artworks. The exhibit will open Jan. 29 at Baltimore’s Notre Dame University of Maryland; this coincides with the launch of the university’s new art therapy program.

Elizabeth wanted to see pieces of artworks in person, so our itinerary brought us first to Beit Terezin, located about an hour’s drive north of Tel Aviv at Kibbutz Givat Haim Ichud.

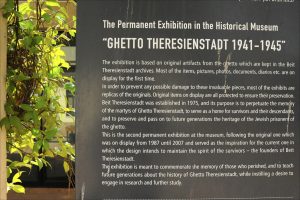

The Beit Terezin campus includes a museum, art exhibition halls, library, educational center and archives. It was established in 1975 in memory of the Jewish martyrs of Theresienstadt Ghetto — a “model camp” in Czechoslovakia that the Nazi propaganda machine used to convince the world that they were actually treating the Jews well, and that stories of mass extermination were completely false.

In fact, Theresienstadt achieved notoriety for its so called “beautification” program, which began in 1943 as the Nazis prepared for the visit of a Red Cross delegation. Shops and cafes were opened, flowers were planted and playgrounds were planted.

The visit itself, on June 23, 1944, lasted only six hours and was a complete success from the Nazi point of view; the Germans had fooled the world. Shortly after, the transports to the East resumed. Of the more than 18,000 Jews sent to Auschwitz in 11 transports during the autumn of 1944, fewer than 1,600 survived.

Curator and archives director Sima Shachar spoke about the uniqueness of Beit Terezin, which unlike other Holocaust memorials is dedicated to one specific concentration camp.

“We are the only place like it in Israel,” she told us, noting that many Israeli schoolchildren and soldiers, but relatively few foreign tourists, visit Beit Terezin — at least compared to much larger institutions such as Yad Vashem. “You can tell more stories if we’re talking about one place, one camp, one ghetto. For me as an archive director, the story of a person is not only about his time in the camps, but where he grew up, his family, what his life was like before.”

She added: “We don’t talk about politics here. We tell the story of Jews who were in the Theresienstadt Ghetto. Once a year we have a special seminar with history and music, and young musicians come for master classes. We are making a connection with the music composers wrote in Theresienstadt and performed,” she said — from classical to cabaret — “and even music the Nazis did not allow” such as jazz and blues.

Theresienstadt functioned as a Nazi concentration camp from its establishment on Nov. 24, 1941, until its liberation by the Soviet Red Army on May 8, 1945.

At its peak, more than 58,000 Jews were crammed into a walled ghetto built in the late 18th century for 7,000 people at most. Everyone between the ages of 14 and 65 was required to work, and children were forcibly separated from their parents.

“Life in other ghettos was very hard, but at least the family could be together — children, parents, grandparents. Even if you were hungry, you were with your family,” Shachar said. “But in Theresienstadt, from the beginning, the Nazis separated families. And you didn’t know for how long you were coming. It could be a few days, a few months or a few years.”

Shachar has been working at Bet Terezin for 21 years and is earning a Ph.D. in Holocaust studies. While nobody in her family was interned at Theresienstadt, her mother suffered the horrors of World War II as a child in Ukraine.

“The idea to build something after the war — to tell the story of the people who lived in Theresienstadt — actually started during the 1940s,” said Shachar. Among the artifacts displayed at Beit Terezin: a Monopoly board drawn by Oswald Pöck (1893-1944); a Hohner harmonica played by a camp inmate, and a handwritten German-Hebrew dictionary.

Besides an index of the 162,000 Czech, Slovak, Austrian, German, Dutch, Danish and other Jews imprisoned in the ghetto, the archive also contains 200 children’s drawings and 500 to 600 works of art by adults — including those by prominent artists Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, Emanuel Groag and Friedrich Ferber.

Beit Terezin receives money from the Claims Conference as well as Israel’s Ministry of Culture and Education. It also occasionally receives donations from private sources as well as group visits.

While not particularly well known among ordinary tourists, Beit Terezin does draw a number of visitors from the Czech Republic — particularly teachers coming to Israel for seminars about the Holocaust — as well as people from Spain, Portugal and Germany.

Yet some elderly Jews who actually survived Theresienstadt and ended up in Israel have not made the pilgrimage to Beit Terezin. “Not all of the survivors wanted, or want, to be in contact with a place that commemorates the Holocaust,” said Shachar. “They want to live their lives and forget about it.”

Our next stop was the better-known Ghetto Fighters Museum, which is visited by about 100,000 people a year and located off the busy highway linking Akko with Nahariyya.

Anat Bratman-Elhalel, the archives director here, said the museum — known in Hebrew as Beit Lohamei Hagheta’ot — was founded in 1949 by Holocaust survivors, including members of the Warsaw Ghetto underground. The world’s oldest museum devoted to the Shoah, its first curator was Russian-born Miriam Novitch, a member of the French resistance who was liberated by the Americans in 1944 and devoted the rest of her life to Holocaust research.

“Miriam Novitch used to travel all over Europe, collecting art and writing books. She met artists themselves or members of their families. She saw the art as kind of spiritual resistance,” Bratman-Elhalel said. “That’s a phrase she coined. It wasn’t just holding a gun or throwing a Molotov. Anyone who drew in hiding or in the camps to document what he experienced — or express his feelings, even though it forbidden to do so — was a kind of spiritual resistance.”

Thanks to the efforts of Novitch (who died in 1990) and others like her, the Ghetto Fighters Museum today has 5,000 pieces of art. Most of them were made during the Holocaust, and others immediately after. Three years ago, said Bratman-Elhalel, the museum received 70 drawings made by an architect, Willy Ochs, during his time in the Janowska concentration camp, in Nazi-occupied Poland.

“He had kept them all these years, and 20 years after his death, his daughter decided to donate them to the museum,” she said, adding that most of her institution’s art is not on display. “We have temporary exhibitions that we replace every three months. We have no more art curator because of budget issues. I wish we had an art curator.”

The museum’s collection is vast, but a few pieces stand out in my mind. One is a 1945 charcoal and colored chalk sketch by Jozef Bau of concentration camp inmates in their striped uniforms dividing a loaf of bread.

Another is an unnamed work by video artist Romy Achituv, in which with the names of 4,500 places in Europe where Jews lived — in both Hebrew and Latin characters — are projected onto a blank dark wall, constantly forming names which then break apart and float up toward the top. It is a surreal piece of art that symbolizes the breakup of Jewish communities.

Our visit to Beit Terezin and the Ghetto Fighters Museum also had a profound impact on my friend Liz, who has a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from Carnegie Mellon University as well as a master’s in art therapy from New York’s Pratt Institute. She is currently a doctoral candidate in Mt. Mary University’s Professional Doctorate of Art Therapy program.

“I believe that art therapists need to access resources outside of the professional paradigm of art therapy to help us develop a better understanding and responses to our clients’ existential concerns,” she writes in a summary of her upcoming exhibit. “One way is to investigate art making as it occurred in an extreme historical example. Artwork from the Holocaust documents how art-making affirmed existence when that existence was extremely tenuous. It serves as a reminder of the humanity that can be found in the most desolate circumstances.”

Larry Luxner is a freelance writer with The Washington Diplomat and former editor of CubaNews. Born and raised in Miami and now based in Israel, Larry has reported from every country in the Western Hemisphere. His specialty is Latin America and the Middle East, and he’s written more than 2,000 articles for publications ranging from National Journal to Saudi Aramco World. Larry also runs an Internet-based stock photo agency at www.luxner.com.