Camp Doughboy brings World War I history alive on Governors Island

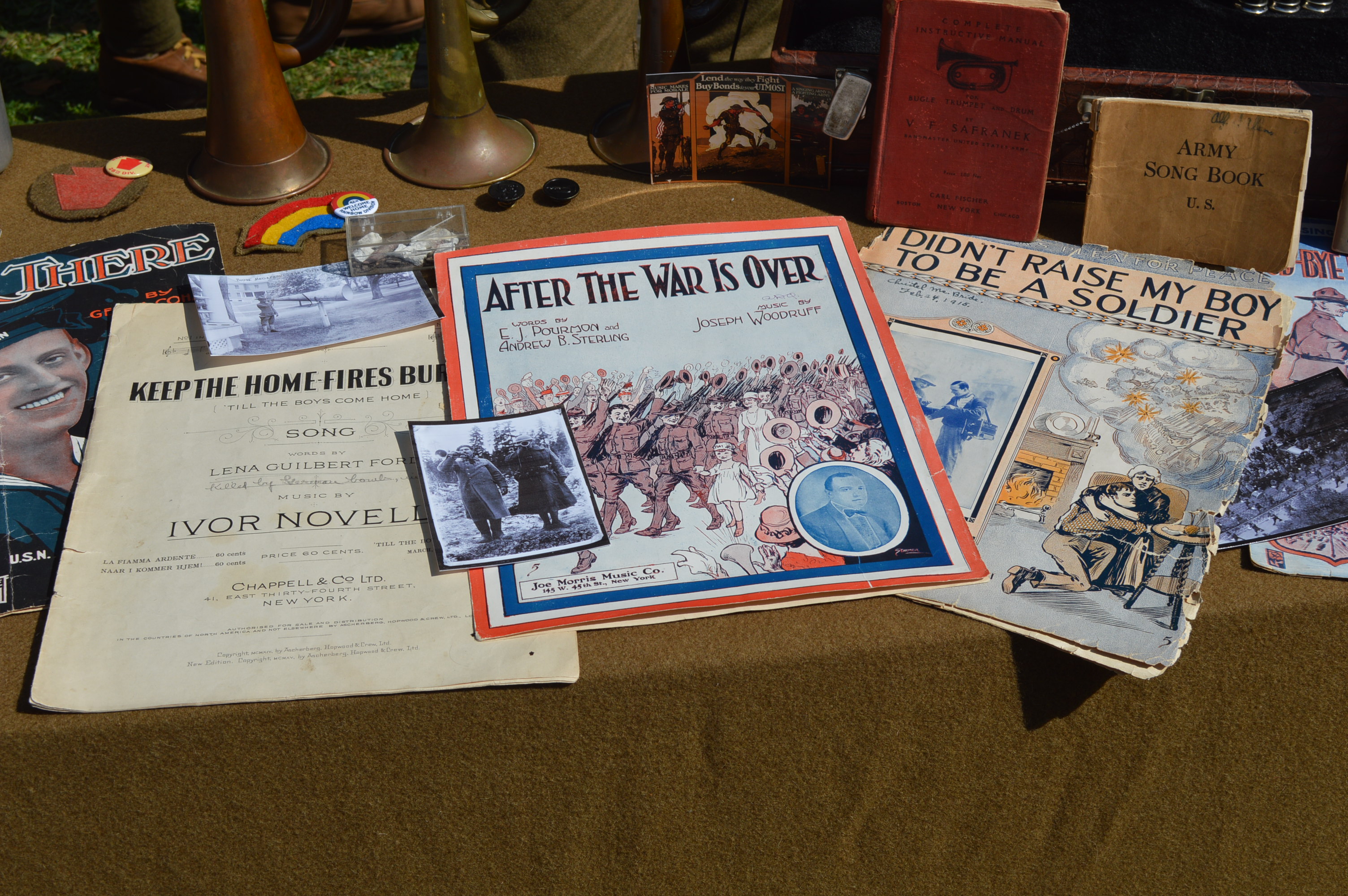

Sheet music from a bygone era at Camp Doughboy World War I Weekend on Governors Island. (Anthony C. Hayes)

New York: It’s a sunny Sunday afternoon on beautiful Governors Island. Couples stroll hand-in-hand around the promenade, stopping now and again to savor the view. Cyclists slowly bike the pathways, while giggling children run to avoid the grasp of their parents’ outstretched arms. It is odd to think, as you look around, that a such a serene and joyful place, just off the southern tip of Manhattan, could have been ground zero for America’s entry into World War I. But an official history of the island records that, in 1917, “In the first act of the war by U.S. armed services, the 22nd Infantry Regiment stationed on Governors Island seized all German-owned cruise ships and ship terminals in the Hudson River in Manhattan and Hoboken. Within weeks, the ships would be used to transport most of the two million American soldiers to France to fight in the war.”

Amongst the two million “doughboys” who sailed for France from the terminals near Governors Island was the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, Gen. John J. Pershing, and his trusted aide, Lieut. George S. Patton.

The doughboys would return to New York, once the war was over, to the cheers of an enormous tickertape parade. And life in the United States as a result of the war would never be quite the same.

Recalling life as it was actually lived and breathed during the WWI-era, military and civilian reenactors gathered on Governors Island last weekend for the third annual Camp Doughboy World War I History Weekend. The intriguing experience – which drew some 8,500 visitors to the bustling encampment – was held on the island’s Parade Ground – some five hundred yards east of historic Fort Jay.

The event was free and open to the public.

“We’re standing here, where Gen. Leonard Wood once was. And Pershing left from Governors Island, so this is the perfect place to hold this event,” said historian Kevin Fitzpatrick. “The National Parks Service has been a great partner. They appreciate the island’s patronage and the way we are using this space. We had 5,000 visitors on Saturday and another 3,500 today (Sunday.) This is the last event we are doing this season, but we’ll be back next year. And of course, we will be participating in the big parade in New York on November 11. We’ll have 100 in uniform for that event.”

There wasn’t any marching while we were there, though Fitzpatrick told us the group had planned to use some its time together to polish their military form. Said polish was evident, however, in the care each participant took in presenting life during the First World War.

The East Coast Doughboys and the Long Island Living History Association provided the breathtaking backdrop. Vintage vehicles were on exhibit, as were displays of artillery, communications, infantry, medicine, and the veterinary corps. Representatives from American Indian House were also on hand to talk about Native American soldiers. (According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs records, more than 10,000 American Indians served in the U.S. Army and more than 2,000 in the U.S. Navy.)

The event also featured presentations by a knowledgeable roster of professional and lay scholars. These speakers included:

Laurie Gaulke – Doughnuts For Doughboys: A WW1 Salvation Army Lassie in Neuvilly

M.M. McMahon – How to Research Your WWI Ancestor

Cheryl Dupris – Native American Heroes

Randal Gaulke – Putting History into Practice: Visiting the American Battlefields of WW1

Stephen Harris – Father Francis Duffy

Keith Muchowski – MAJ John Purroy Mitchel

Libby O’Connell – Food and the War

Ryan Hegg – Rethinking The Greatest Generation

Jeffrey Sammons – The Harlem Hellfighters

Lillian Fehler – Women Doctors and Dr. Anna Tjomsland

Returning to her display table shortly after her talk, we asked Fehler if she would share something with our readers about the women doctors of WWI and tell us a bit about her unique uniform.

“I made my uniform,” said Fehler. “I did my best with it. There are very few photos of this type of uniform. I have a copy of one of Dr. Elizabeth Hocker, who was photographed while serving in France. I didn’t obtain this photo, though, until after I made my uniform, so it wasn’t helpful to me. There is one uniform which survives, and it’s in the Smithsonian. It belonged to a woman who served as a hospital librarian in the United States.”

Picking up on her lecture, Fehler explained the vexing difficulty women doctors faced in trying to enlist in the service of their country.

“As the U.S. was deciding to enter World War I, it was clear they needed to staff their medical corps. So they put out a call for physicians to enlist. Lots of women wanted to enlist, and at that point, about six percent of the physicians in the United States were women. That may sound like a small percentage, but we’re talking about thousands of people. A lot applied, but were turned down because women had never served in that capacity. This enraged many women’s organizations; women’s colleges. They petitioned the military and asked, ‘How do we serve?’

“Due to this pressure, in 1918, the Army medical corps allowed the women to enlist on a limited basis. The Medical Women’s National Association recommended that a certain number of women be considered. Of those, 55 were accepted and went on to serve. Dr. Barbara Hunt, who served with the American Women’s Hospital – which was formed by the Medical Women’s National Association – was a graduate of Johns Hopkins. She was thirty-four at the time. Her unit served under the French military.

“There was one other – Dr. Anna Tjomsland – who enlisted through other channels. She is the one I talk about, because she is the one about who most information survives.”

Fehler told us that Tjomsland was a Norwegian immigrant and one of the first women interns at Bellevue Hospital when she graduated from Cornell Medical College in 1914.

“The way that hospital units which served in the First World War were formed, was they were organized by institutions in the United States. Bellevue formed their unit and Dr. Tjomsland wanted to join. She enlisted as a secretary, and that’s how she got to France.

“When her unit arrived in France, they were posted in Vichy and renamed ‘Hospital Unit Number 1.’ They were short-staffed, so Dr. Tjomsland received her own ward.”

While it might seem the Army fully gave in to the pressure of the women’s organizations, women doctors were far from equal with their male counterparts.

“Women were enlisted in April 1918, but Dr. Tjomsland did not receive her enlistment until December, and this enlistment was not as a full officer. The women were listed as contract surgeons, which meant they were still civilians. They did the work of an officer, but they did not have the rank.

“It’s hard to say with certainty that none of the women physicians were considered veterans. I haven’t looked up what records remain for all of those who served. But they received no pensions, and the National Archives has no information about them. They received no awards or recognition for their service from the Army. At the end of the war, they were mustered out and that was it,” said Fehler.

* * * * *

For more information about World War I, including upcoming events and the effort to build a WWI monument in our nation’s capitol, please read our other stories here, and visit The United States World War I Commission.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”