Saturday Night Live’s legacy: Beyond the laughs

The cast of SNL’s 41st season (NBC)

In a nation as huge, diverse and easily distracted as ours, few things can unite and entertain us like TV. And few programs have thrived for as long as Saturday Night Live. In its 41st season, SNL has had the ability to gather countless weekly viewers for longer than most shows’ entire life spans.

SNL, at its heart, has always existed to make us laugh, and it’s both reflected and influenced the nation’s collective sense of humor over time. Along the way, the show has earned a role in the overall viewer’s consciousness- one that extends far beyond fleeting jokes.

Broadcasted live for 93 minutes at 11:30 each Saturday night, it’s produced not only some of the most iconic characters, images and quotes in American comedic history, but also bred some of the most beloved actors. It brought us back to reality in times of hardship, and maybe even influenced our presidential elections. Over the years, SNL has served to entertain, inform, challenge and comfort the masses.

Making comedy cool

When SNL debuted in 1975, after Johnny Carson asked NBC to stop airing reruns of The Tonight Show on weekends, its genre wasn’t exactly groundbreaking. Sketch comedy and variety shows weren’t unfamiliar to an American audience. But, as compared by authors Tom Shales and James Andrew Miller in their book on the show’s history, Live From New York, “tea had been around for centuries…but the notion of throwing mass quantities of it into Boston Harbor was new. It was revolutionary. So was Saturday Night Live…it sparked a renaissance in topical, satirical, and political humor both on television and off it” (Miller and Shales 8).

SNL was designed to be “the television generation’s own television show,” appealing specifically to the massive, Baby Boomer generation (then just young adults) in a way that “hugely expanded the parameters of what was ‘acceptable’ material on the air, bringing it much closer to the realities of everyday American Life, and helped bestow upon the comedy elite the hip-mythic status that rock stars had long enjoyed” (Miller and Shales 8-9). It revitalized television comedy, giving it a fresh boost of young, edgy talent which combined excitingly with the thrill of live TV.

For 41 years, it’s attracted world-class guests, influenced American pop culture not only in its sketches, but also in films and music, and has even inspired its own Ben & Jerry’s flavors. Put simply, Saturday Night Live made comedy cool.

While the show has faced its share of ratings ups and downs, it’s faithfully shown up for America each week to make us smile, push the envelope, and continuously churn out what often become household names. SNL has traditionally made “stars of unknowns, and superstars of stars” (Miller and Shales 8), and it’s propelled the careers of many treasured names in comedy history (fan or not, can you picture the industry without Billy Crystal, Steve Martin or Adam Sandler?).

With its reliable, weekly visits, the cast of SNL functions as something of an extended family for many fans, who feel a connection with them that’s hard to create in other entertainment mediums. We bond with the cast, heightening our laughter when they succeed, and amplifying the pain when things go wrong- like the untimely loss of members like Gilda Radner, John Belushi, Chris Farley and Phil Hartman, which translated for so many as the loss of a close friend.

Risky (show)business- What will happen next?

Along with nurturing the careers of some of our best-known actors, SNL has also birthed some of the most memorable and quotable moments in TV history. Some have been scripted, some awkward “whoopsies,” and plenty have sparked nation-wide controversy as events both planned and, well, not, occasionally throw grenades into the spectrum of what’s acceptable on live TV.

During SNL’s very first season, host Richard Pryor (who inspired the show’s first brief broadcast delay) engaged with Chevy Chase in the classically uncomfortable sketch titled, “Racist Word Association Interview.” In the sketch, the two turn a simple word association exercise into a hot-potato game of insults that become increasingly risqué, culminating in some of the more… ahem…offensive racial terms in the English Language. The bit was shocking to audiences at the time -which was exactly what the writers wanted- and it set the tone early on for SNL‘s trademark edge.

An example of a less-planned (though no less iconic) SNL “surprise” that sent tremors through the entertainment sphere came during a performance by Sinead O’Connor in 1992. In protest of alleged child abuse in the Catholic School System, O’Connor performed an a cappella version of Bob Marley’s “War,” after which she held up a photograph of Pope John Paul II, tore it apart, and threw the pieces at the camera. The act caught audiences, censors, and the SNL producers completely off-guard.

As Lorne Michaels (SNL‘s famed creator and executive producer) recalls, “I was stunned, but not as much as the guy from the audience who was trying to charge her and destroy the show…He had to be taken away by security” (Miller and Shales 391).

For a long moment after the event, the studio sat in awed silence as the show’s techs refused to illuminate the “applause” sign. But, despite outrage from many viewers, SNL team members, and network bosses alike, the moment was promptly commended as an essential example of what made the show what it was. As said by one NBC Executive at the time, “when we go too long without controversy, something’s wrong. This show is supposed to be the adolescent that’s not obedient to authority” (Miller and Shales 392).

The O’Connor event is just one of many to shock America over the years, and lives in a mixed bowl of mishaps large and small (such as Ashley Simpson’s famous lip-syncing disaster) that have kept SNL exciting, and viewers eager to watch.

Bridging the gaps…by affectionately mocking them!

Another factor in the longevity of SNL may be its use of humor to speak to people of all age groups, social classes, and ethnicities, giving voice to groups that are often a bit overlooked in the general American dialogue. One major example is SNL‘s common nods to the Jewish community, which many in the show’s history are a part of, especially during holiday seasons when the faith is somewhat passed-over in pop culture. Over the years, they’ve produced several bits highlighting what it means to be Jewish during Christmastime. These sketches most often lean more toward endearing than offensive, even when they’re fueled almost entirely by stereotypes.

For example, in a sketch aired in December of 1989, Jon Lovitz donned a long beard, fuzzy blue and white hat, and gift sack decorated with a menorah to play “Hanukkah Harry”– an alternate holiday hero who steps in when Santa catches the flu. Hanukkah Harry, with his classically Jewish accent, hops in his sleigh (powered by donkeys with names like Moische and Schlomo) and travels to the North Pole to save the day.

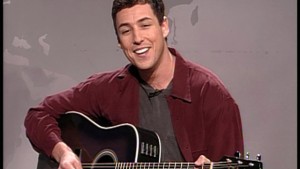

Perhaps the most remembered holiday shout-out to the Hebrew community came in 1994, with the first introduction of Adam Sandler’s tribute to Jewish kids at Christmas, “The Hanukkah Song“. During Weekend Update on December 3, a sheepish-looking Sandler prefaced the song with, “When I was a kid, this time of year always made me feel a little left out, because in school there were so many Christmas songs, and all us Jewish kids had was the song ‘Dreidel, Dreidel, Dreidel'” (Shouse and Timberg 134).

He goes on in his trademark, goofy voice to list famous names of the Jewish faith, like David Lee Roth, Arthur Fonzarelli and Mr. Spock. The song is light-hearted, relatively stupid, and at times will do anything to rhyme with “Hanukkah” (“So drink your gin and tonikah, but don’t smoke marijuanikuh”). But, Sandler’s nonsense is balanced with a tangible warmth.

This allusion to the Jewish during the holidays would become a recurring motif for SNL, in pieces such as 2005’s animated short, “Christmastime for the Jews,” and more recently Vanessa Bayer’s recurring “Jacob the Bar Mitzvah Boy.” With these pieces, as they’ve always done, the writers at SNL nudge the boundaries of acceptable religious commentary, while still showing a winking respect for the community.

Sometimes, the stereotyping teeters close to “too easy,” no matter what group the piece is focused on. But, thanks to a staff that has carefully honed the act of affectionate satire over many years, it’s almost always clear that these bits are meant to inspire laughs of recognition from those being parodied, rather than actual offense. With this delicately applied skill, the writers demonstrate “how humor can be used to cross social divides” and bring us together in laughter (Shouse and Timberg 141).

The healing powers of humor

SNL’s ability to unite has been valuable during times of sadness, when audiences are most in need of comfort and a few restorative laughs. The foggy bewilderment and despair that hung over us in the aftermath of 9/11 is an obvious, and still vivid, example of a time when Americans were in desperate need of someone to take their hands, and lead them to something brighter. SNL, whose home in Manhattan was so close to the disasters, stepped up to the plate.

In the weeks immediately following the attacks, as the country struggled make sense of things and regain balance, laughter seemed a far-away luxury. At first, many comedians felt uncomfortable with continuing their acts as normal. Several high-profile programs took a short break from production, as comedians “embarked on an unusually serious assessment of comedy and its proper role” in a society that had been so severely bruised (Achter). As said by former cast member Amy Poehler, “even thinking about…your work in comedy seemed kind of frivolous at the time” (Miller and Shales 532).

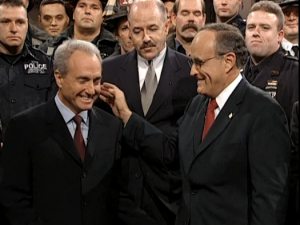

On September 29, 2001, not quite three weeks after the events, SNL decided to go on with their season premiere as scheduled. However, before diving back in, they began with a special cold open featuring then-Mayor of New York City Rudy Giuliani, who had encouraged producers to go ahead. In his words, “people [had] to get back into learning how to laugh and cry on the same day, because they [were] going to be doing it for a long time” (Miller and Shales 533).

After a somber performance by Paul Simon, Mayor Giuliani stood onstage surrounded by a number of solemn-faced, uniformed members of the NYPD and NYFD. He addressed the audience in the studio and across the country, calling SNL “one of New York’s greatest institutions,” and assured us all that having the show “up and running [sent] a message that New York City is open for business” (Jensen).

After the Mayor’s brief speech, Lorne Michaels asked him, “Can we be funny?” With a pause and a smirk, Mayor Giuliani replied, “Why start now?” (Achter)

This single, small joke was a necessary crack in the ice that had suspended the country in grief. For the first time in weeks, the nation as a whole let out a collective, cleansing exhale, as if we all had official permission to entertain the idea of feeling and behaving normally again, in New York City and as far as SNL’s broadcast could reach. “Paralleling his mobilization of America’s first city- its firefighters, police officers, and victims of the attacks,” Mayor Giuliani “had now mobilized a comic institution in the service of a country’s need to laugh.” (Achter)

Altering perceptions, for better or for worse

In recent years, as our nation and our daily lives have changed to fit a post-9/11 existence, SNL’s ability to make light of even our most reviled enemies would prove valuable in our ability to cope with the world’s tensions. On the show, those we’d deemed “scary” became bumbling morons not to be feared. The show’s trend of diminishing those who intimidate us continues, and sometimes we become so familiar with these caricatures that they actually begin to overshadow their real-life counterparts in our minds.

However… it’s not just our enemies that SNL has bred somewhat dominant, alternate versions of. Over the years, the show has employed many different cast members to portray many different public figures. Sometimes those parodied are famous household names in the news. Sometimes they’re lesser-known figures who have recently drawn attention to themselves in one way or another. Sometimes they’re neither, such as the show’s random, recurring portrayal of Fleetwood Mac’s Lindsey Buckingham as an ever-forgotten game show panelist. In any case, SNL’s exaggerated versions of those they satirize have had a historical tendency to…well, stick.

No public figures are more aware of SNL’s powers of reinvention than politicians. Through the seasons, among many others, we’ve gotten to know Dana Carvey as George H.W. Bush, Darrell Hammond as Bill Clinton, and Will Ferrell as George “Dubyuh” in some ways better than we’ve gotten to know the real politicians. With each election, the question arises if these over-the-top clones may actually have an impact on voters’ perspectives of the real politician- a question that’s followed none other quite like it has Sarah Palin, John McCain’s 2008 running mate.

Tina Fey first appeared as Palin during the show’s 34th season premiere (as a guest- she’d left the show a couple of seasons prior). The “Palin” debut depicted a joint speech on feminism in politics, in which Amy Poehler appeared as Hillary Clinton “quietly seething over the fact that Palin was still in the race when she was not” (Day and Thompson 118). In contrast with Poehler’s pissed-as-hell Hillary struggling to sound professional, Fey’s Palin was unabashedly showy as she “waved her hand to the audience like a beauty queen, offering a side profile of her bust, and then posed as if she were cocking a rifle” (Flowers and Young 56).

Fey’s memorable visual performance, head-turning resemblance, and reality-driven punchlines combined to create an image of the Governor as an absurdly detached cougar, which became nearly impossible for her to shake.

This first performance, in which Fey’s only props were her own observations of the politician, “Kawasaki 704 glasses and a wig,” earned SNL the highest ratings for a season premiere since Al Gore hosted six years prior, reached well over 14 million views on Hulu, and broke viewing records on many other websites (Flowers and Young 49).

Fey would appear a few more times that season, such as in a sketch re-creating Palin’s famously unfortunate interview with Katie Couric. In this impression, Fey “largely used Palin’s own words and embellished them to highlight her naivety and nonsense, ultimately creating a vision of the politician as hopelessly vapid and uninformed” (Day and Thompson 119).

Aiding in this momentum was the fact that more Americans viewed the SNL skits (live and online) than actually viewed the events that they were based on (Flowers and Young, 62). Polls from Fox News, Pew, ABC, CBS, Gallup and others showed favorability ratings for Palin declining from September to November of 2008, as the SNL skits grew in popularity (Flowers and Young 63). While reasons for the decline likely extended far beyond Fey’s portrayal, it’s undeniable that her sharp highlighting of some of Palin’s less “assuring” traits made an impact on public perspective. If Palin ever had the opportunity to be taken entirely seriously as a candidate, a single interpretation of her on SNL, played by a woman who wasn’t even technically a cast member, had the power to permanently alter her chances.

Saturday Night Live’s Palin parody was not their first, or last, influential caricature. But, it may be the most significant example of the show’s considerable impact on Americans’ perception of the people and events that surround us.

The legend lives on

Saturday Night Live may not go on forever. But, its impact on audiences and comedy culture itself will always have its own, lengthy chapter in the history of American entertainment. Today, SNL proudly stands as the longest-running sketch comedy program in TV history. Through almost half a century, it has lived as a sort of “keepsake to be handed down from generation to generation,” both by cast members and an audience that’s “perpetually replenished, as new legions of viewers come of age” (Miller and Shales 9).

From its very first broadcast in 1975, SNL has been a trendsetter in “American mores, manners, music [and] politics,” and that influence continues still (Miller and Shales 7). The show has set comedy standards, introduced icons and torn through boundaries. It’s injected countless jokes, quotes and characters into the American entertainment scrapbook, given voice to the quiet, and maybe even influenced our political history, if just a little. Most importantly, though, Saturday Night Live has always made us laugh, “even when it hurt” (Miller and Shales 9).

References

Abel, Angela D. and Barthel, Michael. “Appropriation of Mainstream News: How Saturday Night Live Changed the Political Discussion.” Critical Studies in Media Communication, vol. 30, No. 1. Pages 1-16. March 2013. Web. 11 November 2014. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-bc.researchport.umd.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=2156779f-9b11-4241-8918-72404c9bbb27%40sessionmgr114&vid=0&hid=105

Achter, Paul. “Comedy in Unfunny Times: News Parody and Carnival After 9/11.” Critical Studies in Media Communication, vol. 25, no. 3. Pages 274-303. August 2008. Web. 11 November 2014. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-bc.researchport.umd.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=aaaed4af-bd8a-443a-ade1-3a4a67728e5c%40sessionmgr114&vid=0&hid=105

Day, Amber and Thompson, Ethan. “Live From New York, It’s the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody.” Popular Communication, 10. Pages 170- 182. 2012. Web. 11 November 2014. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-bc.researchport.umd.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=21fbca64-7203-48fc-8709-53b7a47007c9%40sessionmgr112&vid=0&hid=105

Flowers, Arlene A. and Young, Cory L. “Parodying Palin: How Tina Fey’s Visual and Verbal Impersonations Revived a Comedy Show and Impacted the 2008 Election.” Journal of Visual Literacy, vol. 29, no. 1. Pages 47-67. 2010. Web. 11 November 2014. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-bc.researchport.umd.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=cc359d66-b41b-4532-adac-141ca00c67d5%40sessionmgr114&vid=0&hid=105

Jensen, Elizabeth. “Mayor Giuliani Helps ‘SNL’ Get Back to Funny Business as Usual.” The Los Angeles Times. 30 September 2001. Web. 17 November 2014. http://articles.latimes.com/2001/sep/30/news/mn-51635

Miller, James Andrew and Shales, Tom. Live From New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live, as Told by its Stars, Writers and Guests. Back Bay Books, 2003. Print.

Shouse, Eric and Timberg, Bernard. “A festivus for the restivus: Jewish-American comedians respond to Christmas as national American holiday.” Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. Pages 133- 153. 2012. Web. 11 November 2014. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-bc.researchport.umd.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=6987c7e6-9e8e-454c-947e-47eb68959f8f%40sessionmgr198&vid=0&hid=105

Lauren Molander, a Baltimore native, is on a long-winded journey to find her place in the world. She majored in Media and Communications Studies at UMBC, and hopes to build a career working with words.

Lauren is unusually enthusiastic about roller coasters, SNL, fancy teas, cosplay culture and the broody music of her early teenage years. In her free time, she can be found playing with makeup, beating the same video games repeatedly, begging her cats for affection, reading books by funny people and binging on anime.

She is still waiting patiently for her (tragically delayed) letter from Hogwarts.