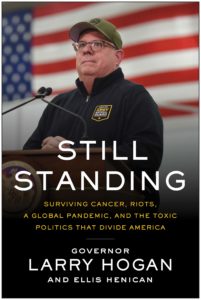

Can Larry Hogan Win the GOP Nomination in 2024?

At his 2019 inaugural ball, Gov. Larry Hogan goofed around with a purple surfboard given to him by his State Police protection detail. In his new book, Hogan describes surfing the Democratic blue wave in the 2018 election that left other Republicans under water. Governor’s Office photo

This an expanded version of a column by Maryland Reporter’s Len Lazarick that runs in the August issue of The Business Monthly, serving Howard and Anne Arundel counties.

For someone like me who’s been following his political career for the past nine years, the basics are well-known. I was present at many of the key events he describes in the book. But the book is not intended for people like me or even Marylanders. It is meant to introduce Hogan to a national audience. Hence his appearance on national cable and radio shows – not local outlets.

Even for locals, the book does shed light on his thinking at crucial times and the internal dynamics of his campaign and administration, run by a tight group notoriously tight-lipped about how decisions are made.

Family life

His family life, schooling and personal life were particularly interesting. That his father, Larry Hogan Sr., the former congressman and Prince George’s County executive, was a dominant figure and aspirational model for junior even to this day is reinforced throughout the book. The son fulfills the father’s political dreams for them both.

Yes, we had heard Hogan Jr. was a lifeguard when he lived in Florida with his newly divorced mother as a teenager, but we didn’t know his primary job was selling sun-tan lotion to women swimming at resort hotels.

Yes, we had heard Hogan Jr. was a lifeguard when he lived in Florida with his newly divorced mother as a teenager, but we didn’t know his primary job was selling sun-tan lotion to women swimming at resort hotels.

We had heard that he met his wife Yumi Kim at an art show in Columbia, but we didn’t know how this unlikely paring – he had been “dragged” to the gallery at Howard Community College – evolved as this lifelong bachelor, then 44, pursued this Korean-born single mother of three daughters to become the rock of his life and his “instant family.”

We knew about his personal bankruptcy as a real-estate developer in the 1990s, but he makes the pain of this failure palpable.

Runs for Congress

We were aware of his 1992 challenge to Congressman Steny Hoyer, now House majority leader, giving Hoyer the closet race in the 20 elections of his long career in Congress. Curiously though, there is no mention at all of Hogan’s failed 1981 primary bid in the special election that Hoyer had won to take the seat once held by Hogan Sr.

Much of the book is a detailed recounting of the campaigns showing how a “center-right” Republican managed what seemed unlikely if not impossible — becoming only the second Republican in blue-state Maryland history to win two-terms as governor. As a close observer of both campaigns, most of Hogan’s reconstruction appears valid, though most everything reflects well on the candidate.

Hogan certainly admits flaws. “I’m not the smartest person in the world,” but he knows how to surround himself with a bright team.

Hogan is the hero in key chapters. Almost a third of the book is spent on the two big challenges months after taking office. He confronted the riots in Baltimore over Freddie Gray in police custody and Hogan’s life-threatening diagnosis with lymphatic cancer.

Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake takes a lot of the heat from Hogan, as does state’s attorney Marilyn Mosby. These chapters were released early to the Baltimore Sun and there has been pushback and disputes about how Hogan characterizes events.

Rawlings-Blake, in a Sun Op-Ed, said, “Governor Hogan uses Baltimore’s uprising to promote himself while criticizing and diminishing members of the Black community,” including herself and President Obama.

It is safe to say that it was Hogan’s forthright and visible response to both riots and cancer that solidified his reputation and popularity.

Bipartisan

Throughout the book, Hogan emphasizes his “bipartisan” approach to governance. He supplies limited evidence to what this actually means in practice.

Hogan defeated Lt. Gov. Anthony Brown mainly by tying him to the many tax, toll and fee increases under Gov. Martin O’Malley, 43 to be exact. Rolling them back was one of Hogan’s key promises, with very limited success. One of them was the so-called “rain tax,” a mandated tax on impervious surfaces to be used to clean up stormwater.

Hogan pushed its repeal, Democrats proposed their own version, and that repeal passed almost unanimously. The bill removed the mandate for the tax, but the counties still had to come up with the money to pay to clean up stormwater. Hogan was also able to roll back the toll increases on his own, because that was done by the Maryland Transportation Authority, an agency he controls. It did not require legislative approval.

His book does not mention the number of times he tried to cut taxes in general or for specific groups like retirees that the legislature refused to seriously consider. Much of the “bipartisan” governance was Democrats passing their own version of a Hogan proposal. He mentions that Democrats had the votes to override his vetoes, but he gives no examples of when they did, such as the $15-an-hour minimum wage he strongly opposed.

What Hogan seems to mean by “bipartisan” is that he is able to win the support of enough Democrats and independents to win a statewide election in Maryland – and keep that support as governor. The voters’ more progressive representatives in the General Assembly are not so willing to go along.

He freely admits he deliberately avoids the hot button social issues that have characterized the Republican Party’s shift to the right. While Democratic opponents get their share of swipes and snark, Hogan saves some of his stiffest jabs for Donald Trump and the toxic atmosphere in Washington. With ample evidence, he blames Trump for the “blue wave” Hogan was able to surf to victory in 2018, while his party lost executive races and legislative seats around the state.

Hogan touts his success acquiring 500,000 coronavirus tests from South Korea with the help of Yumi, which gained national attention. He reprised it in a Washington Post article that led its Sunday Outlook section in print on July 19.

But follow-up stories have questioned the price and utility of the tests, including a Washington Post story saying they could have been bought cheaper in the U.S.

Publishing books has a long timeframe, so they can be out of date before they come out. Hogan calls his early approval of the Purple Line, the light rail line in the D.C. suburbs, “the largest public-private transit project in North America.” Now its private partners are threatening to pull out as the project is a year behind schedule and $755 million over budget. (Hogan makes no mention of the canceled Red Line in Baltimore, the subway project he rejected because he believed the costs were underestimated. Some Baltimore leaders have never forgiven him.)

Audience beyond Maryland

He concludes with a message for an audience far beyond Maryland.

“One thing I’ve learned is that what most people want from their leaders is an optimistic, can-do, results-oriented approach. People just want the problems solved. They are sick and tired of divisiveness and paralysis. They believe that civility and pragmatism are more effective. They don’t think compromise is a dirty word…. These are things that my Republic party is going to have to focus on if it expects to have a future and win national elections again.”

Hogan is clearly eyeing a run for president. On Facebook and conservative blogs, it is already being dismissed as the wishful thinking of a RINO, Republican in Name Only. It is a style and strategy that got Hogan elected in Maryland, but others feel it won’t play well on the national stage.

Mark Levin, a leading voice of the Republican right-wing on TV and radio, writes in Red State on July 17: “In the end, as I’ve written before, Hogan is not the future of the party, and he’s wasting his time and everyone else’s by attempting to be. He’s a good fit for Maryland, a deep blue state that would otherwise have a Democrat in charge, but there’s no way the GOP base is going to get behind a guy who’s pro-Roe v. Wade, pro-gun control, and pro-tax-raising.”

There’s slim to no evidence from Hogan’s first term that the governor favors abortion, gun control, and higher taxes. Except for attempts to reduce taxes, he has let stand Maryland’s laws on abortion and guns, though progressive Democrats believe otherwise.

His book makes the case that he has tried to govern from the center. At the moment, the center is out of favor with the most partisan of Democrats and Republicans. Hogan is hoping that it will become as popular in the nation as it has been in Maryland.

Len Lazarick was the founding editor and publisher of MarylandReporter.com and is currently the president of its nonprofit corporation and chairman of its board. He was formerly the State House bureau chief of the daily Baltimore Examiner from its start in April 2006 to its demise in February 2009.