Brooklyn 2020

Derelict housing on 8th Street, Brooklyn (Photo by Jeremiah Hannon)

If you need to get some cutlery sharpened, go down to the Grinding Company of America, across the Vietnam Veterans Bridge on Annabel Street in Brooklyn. The Grinding Company of America used to be located across the street from Camden Yards for around a century before the baseball stadium was built, convenient to all the produce, meat and fish wholesalers that were located there. Then the wholesalers moved out to Jessup, the stadium was built, parking got desperate, and the company’s owner got frustrated at the number of tickets he got written for parking near his own business.

Once across the bridge, you will see the fishermen and crabbers working the Patapsco River and nearby marshes, despite what the aquatic life in the river has absorbed from two hundred years of industrial pollutants deposited there. Crossing another bridge on Potee Street, there are discreet signs of homeless encampments in the brush on both sides of the street. Then there is the split – one road leading left down Frankfurst Street to the scrap yards and carport terminals of Fairfield, where Bethlehem Steel once built ships, and Potee Street continuing on the right past a solid and simple sign welcoming you to Brooklyn proper.

The main streets of the area are South Hanover Street, a commercial corridor that runs south down into Anne Arundel County, and East Patapsco Street, going parallel to the harbor, inland and separated by railroad tracks from industrial Fairfield, the Brooklyn neighborhood continuing on the numbered streets until you cross West Bay Avenue and enter Curtis Bay on the southeast.

Knives sharpened promptly and well, gaze around at the antique cutlery, used commercial kitchen knives and scrapers for sale, abandoned by failed restaurants, and observe a couple of samurai type swords in scabbards, ready to be picked up. Leaving the whirring of the continuously employed grinders behind, drive around the neighborhood, and take a look around.

Annexed by the City of Baltimore in 1918, Brooklyn grew from a sleepy village into a bedroom community for the shipbuilders and longshoremen who worked along the waterfront. It was a blue-collar neighborhood, “that had pride,” one longtime resident said, “ a lot of the people worked at Maryland Dry Dock, Grace Chemical in Curtis Bay and the other industrial plants in Fairfield.”

Many of these residents moved to Brooklyn like it was “coming to the promised land,” leaving other neighborhoods such as South and West Baltimore and Pigtown – communities that were crowded and noisy, moving from small rowhouses to single-family homes with porches, a “suburbia in the city.”

Another longtime resident recently reflected, “We loved coming over the Hanover Street Bridge (now the Vietnam Veterans Bridge),” thinking “what a beautiful, pristine area” where they “never locked their doors.”

A decade ago, Brooklyn was an “iffy” neighborhood. Businesses would come and go, the stalwart hanging on, encouraged by the city’s plans – the construction of the new courthouse on Patapsco Avenue, development promised in nearby Westport spreading their way, and the grit of those determined not to give up their investment in a community where they were raised.

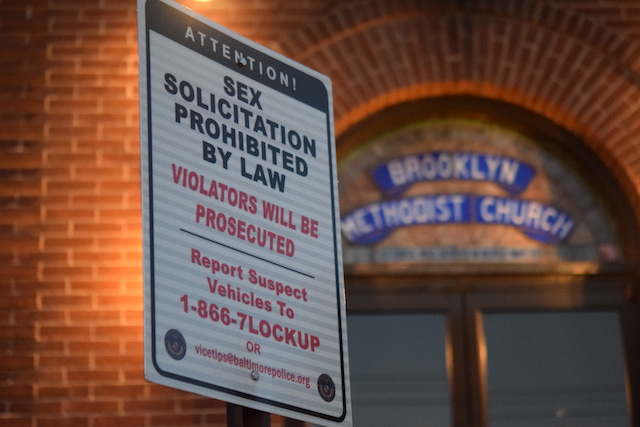

In the last decade, and particularly in the last five years, it is said by neighborhood activists that Brooklyn has deteriorated considerably. “The opioid epidemic has really brought the area down,” said one emergency medical provider. Prostitutes ply the area and have been moving with their clientele off the main drags onto the residential streets, endlessly annoying the homeowners. “They have no respect for the neighborhood,” one native said, “and they do what they do, you know, right outside our front doors.”

One prostitute even “threatened to burn down my house when I said something to her.” Drugs are sold throughout the neighborhood with the accompanying crime and violence. “They [the junkies] break into your cars, they break into your houses,” she continued. “Many older residents have left,” said one local business owner, “and many would if they could.” One resident of over half a century saying she would have stayed but left because the current occupants on the other side of her duplex “were partying all night long and [she was] smelling pot through the walls.”

Near the busy intersection of South Hanover and East Patapsco, there had been a diner, closed by fire and now a convenience store with hand-painted signs advertising acceptance of EBT cards. An orthopedic shoe store, a duckpin bowling alley, and even an archery range are all gone. An Irish pub, once known for its steamed crabs, abandoned.

Other pubs surviving, one advertising it was “for grown folks,” hoping to discourage mayhem by restricting their clientele to those over thirty, another one mostly a Plexiglas shielded liquor store. Traveling down the main streets of Hanover and Patapsco, the litany of the disappeared overwhelms – a hardware store formerly with a legendary hammer hanging over the sidewalk announcing its presence, the video store, the grocery store, the pizza, and sub shop, the latter run by hardheaded immigrants who brooked no nonsense from would-be troublemakers. Gunnings Crab House, well known statewide, sold at auction and now demolished. The family-run restaurant across the street from the District Court, giving up when hoped-for customers from the new courthouse failed to cross the street and have lunch there.

According to 2017 information gathered by the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance in 2017, 7.1% of the residential properties in Brooklyn and the nearby Curtis Bay neighborhoods were vacant and abandoned, compared to 5.6% in Cherry Hill and .3% in the Federal Hill/Inner Harbor neighborhoods. The same survey found 24.2% of the households in Brooklyn and Curtis Bay living below the poverty line, in contrast to 2.3% in the Federal Hill/Inner harbor area, but below the 39.3% living in Cherry Hill.

Baby carriages pushed by teenage mothers are a common sight. A remarkable 46.4% of the children in Brooklyn and Curtis Bay were found to be living below the poverty line and the same neighborhood had 68.6% teen pregnancy rate per 1,000 females aged 15-19 years old. In the Federal Hill/Inner Harbor region the teen pregnancy rate was 10 per 1,000 and 25.9 per 1,000 in Cherry Hill.

Crime statistics establish the Brooklyn/Curtis Bay area as being one of Baltimore’s more dangerous, especially when compared with other nearby Southern Police District communities. In 2017, the overall violent crime rate per 1,000 residents was 29.9, compared to 26.7 in Cherry Hill and 16.5 in the Federal Hill/Inner Harbor neighborhood.

Numbers of shootings per 1,000 residents were similar to that of Cherry Hill, but the number of narcotics calls for service per 1,000 residents was 127.4 in Brooklyn/Curtis Bay as opposed to 46.7 in Cherry Hill and 14.1 per 1,000 residents in Federal Hill/Inner Harbor. A further indication of serious trouble in the neighborhood is the plea by the resident manager of an apartment complex for the police to do something about “the individuals hanging out and conducting business” [drug dealers] who drive off potential renters.

Another reason suspected for the decline of Brooklyn is real estate speculation, which leads to less owner-occupied housing and more absentee landlords who dream of market-rate tenants but rent to the desperate and the poor. A short time ago on 8th Street there were “twenty-two vacant houses, foreclosures, 85% owned by out of town banks,” according to a community leader.

It is among these empty houses and impoverished people that the demon of the streets, drug addiction, thrives, and the principal drug of choice is heroin, which has plagued Baltimore for generations. Originating in the fields of Latin America and Afghanistan, it arrives in Baltimore to be first snorted in boredom, then skin popped in sadness and finally mainlined in desperation where it takes possession of the central nervous system. The individual develops a tolerance and its demand for increasing use results in an enslaved individual whose life goal is to feed the monster by whatever means – theft, prostitution, and selling the poison to others.

The last waves of gentrification in Baltimore failed to reach Brooklyn. The hope encouraged by various promised improvements fading, the establishments continuing are convenience stores catering to the indigent, rehab clinics, storefront churches, and medical centers serving drug addicts and those affected by the long term brain chemistry changes caused by addiction.

Several years back, local and out of town speculators were buying up properties, both residential and commercial, anticipating the developments in South Baltimore moving south and hoping to get ahead of the wave and cashing in. What happened? As mentioned, the courthouse became a fortress in the daytime, closed up after working hours, the employees returning home elsewhere without stopping to support local businesses. The S.N.A.P. (Strategic Neighborhood Action Plan) program launched under the O’Malley Administration in 2002 is long forgotten. The nearby Westport development ended with the State of Maryland’s conviction of the then Mayor Dixon and her involvement with developers A, B and C in 2009.

The speculators lost interest, boarding up their properties and more local businesses who were hanging on by their fingernails surrendering and decamping for the suburbs. The caterers on Patapsco, the Catholic elementary school, gone. The bar with the two concrete handicapped ramps, closed indefinitely by the Liquor Board in March of this year. A notice on the trash-strewn entrance of a shuttered Hanover Street nightclub decries a lack of permits. A pool hall, once celebrated in the local movie legend “Diner,” then became a boxing gym, which one year turned out over half of Baltimore’s Golden Gloves champions, is now a church.

There are numerous nonprofit agencies assisting the struggling Brooklyn population. Two of the larger ones are the faith-based Transformation Center at 4th and Pontiac and the City of Refuge at 9th and Pontiac. Both provide a soup kitchen, recycled clothing, a food pantry, counseling, referrals to rehabilitation centers, drug/alcohol recovery meetings, and safety from the violent streets. At least seven other institutions provide some of these services and all are widely used by those in the 21225 zip code.

The prostitution problem in the neighborhood is a formidable one, and according to one police supervisor in the Southern District, “All of them (the prostitutes) are addicts.” In attempts to break the cycle of drug addiction and human trafficking in the neighborhood, the police department’s Vice Unit occasionally arrests the incoming clientele, but this unit, consisting of “five officers, two women, and three guys,” according to a local beat patrolman, “covers the entire city and can’t be everywhere at once.” For a time local residents were recording the license plate numbers of the prostitutes and sending several dozen “john letters” through the police department to the cruising vehicles’ owners. However, this effort has been stifled following the Baltimore City Solicitor’s advice that this could result in the City being sued. At present, the local beat officers and community activists refer the women to outreaches at Her Resilience, the City of Refuge, community health programs at the Greater Baybrook Alliance and The Well, where they can seek help with their drug addiction, enslavement to pimps and mental health issues.[vii]

Currently, some economic hope for improvement in Brooklyn rests with the “SB 6” program. This organization was created when Sagamore/Weller Development, seeking tax breaks for its Port Covington project, agreed to a Memo of Understanding (M.O.U.) with the City of Baltimore, whereby they would provide funding for local improvements, improvements to be decided jointly by representatives of six local neighborhoods – Brooklyn, Curtis Bay, Cherry Hill, Lakeland, Mt. Winans and Westport – and the developer. So far, this has resulted in a class on “soft skills” (how to fill out job applications, how to interview, etc.) and a job fair by Northern Real Estate Urban Ventures, the project manager for the development of the construction phase. The money promised by the developers has yet to be released following discussions as to how it will be spent – perhaps to be divided by size of each neighborhood’s population, in support of programs already established, etc., according to Concerned Citizens for a Better Brooklyn leader.

These discussions are currently on hold and hopefully will resume in June of this year. Another good sign is taking place along 9th, 10th, and Stoll Streets, where immigrants from Russia, Italy, and other countries are moving into the low rises there. “Hey, they’re trying to do it the old fashioned American way,” says one local public safety worker. “They get into a junk house and start fixing it up, slowly building their own American dream.”

For the present, the residents and business owners hang on, now even further challenged by the coronavirus epidemic. Suspension of eviction procedures by the State of Maryland, while assisting homeowners, also means abandoned housing becomes longer-term havens for addicts, drug dealers, and storage sites for stolen goods. Drug addiction and the ensuing crime aren’t affected, particularly since State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby announced on March 15th that her office would not be prosecuting any prostitution or drug possession cases, including heroin. Youthful drug dealers in black balaclavas continue to flag down customers along 5th Street. Tattooed prostitutes watch for slow rollers and ask for cigarettes from behind crooked aviator sunglasses. When told by the police that group gatherings violate Covid-19 restrictions, people on the street respond by giving the police the finger and twerking.

Rehab health centers like the Concerted Care Group are still open (there are four clinics in Brooklyn dispensing Methadone), but the community-based volunteer agencies have been forced to limit some of their services because of the quarantine requirements.

Several continue their work on a “grab and go” basis, and at one, The City of Refuge, Pastor Billy Humphrey says, “If anything, we’ve ramped up our services,” referring to their food distribution activities, a most necessary charity in a time of growing unemployment.

On Saturday, April 4, three people were shot and wounded in the 400 block of East Cambria Street, in the vicinity of abandoned houses being used for drug dealing. Police found 22 shell casings on the street there. On April 10, three more people were shot in Brooklyn, one of them fatally, near the corner of East Patapsco and South Hanover.[x]

At the edge of the neighborhood, just before you get to Curtis Bay, stands Fred and Margie’s. It is a sit-down restaurant and bar, normally serving lunch and dinner. It remains open for carryout food and drink during the pandemic, but has had struggles even before the contagion arrived, as shown by a conversation between a bartender and a local resident a few weeks before the quarantine.

“Do you know X, older guy, kind of heavy set, drives a truck?”

“ If it’s the guy I’m thinking of, he’s not allowed in here anymore.”

“He’s ok, once you get to know him. I mean past the exterior, he’s ok. Always wears a gray hat. You know him.”

“Oh, yeah, I know him and his hat. He can’t come in here.”

“He’s really ok, once you get to know him…”

The bartender shook her head and walked away from the customer, past the sign that read, “No more tabs. No more credit. Pay when served.”

I coached boxing at the now gone Brooklyn Boxing Club from 2000-2010, and became interested in writing about the neighborhood after observing the last decade’s changes there. I have a Bachelor’s degree in Urban Studies from Fordham University and have published non-fiction in The Baltimore Sun, The Maryland Historical Society Magazine, Soundings, Lekko and the Carriage Horse Journal.