D-Day Conneaut: A baptism by fire into the world of WWII reenacting

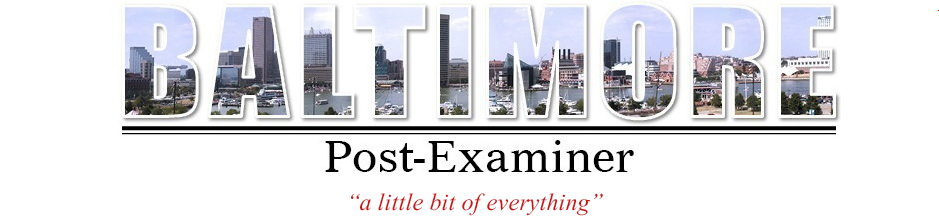

US infantry reenactors prepare for an assault on German forces at D-Day Conneaut. Photo taken with a vintage Argus A3 camera. (Anthony C. Hayes)

One year ago today, my colleague Camilla Hsiung and I were making sensible plans to cover a Battle of the Bulge reenactment at Fort Indiantown Gap, PA. Now we are considering the sanity of spending a couple of icy nights in a canvas army tent, to cover yet another wintry World War II event in wind-swept Pennsylvania.

How did this happen?

How, in one year, did we go from wearing cozy trench coats and stylish berets, to donning the kind of G.I. wear Ernie Pyle would have used during WWII? Where did this footlocker in my living room full of army jackets, trousers, leggings and shirts; canteens, mess kits and helmets come from? Why is there a pup tent on my ebay watch list? What was I doing last August, trying to focus an antique black & white film camera while bouncing across Lake Erie in a duck boat? And when did I go from being a wild-mannered reporter for a great metropolitan news site, to a bivouacking, backpacking, beach-storming member of the 167th Signal Photographic Company?

Where to begin?

I’m a history buff, so I’ve always been attracted to history-centered events. Living in Baltimore, we are bombarded with reminders of the War of 1812. Washington DC – another city rich in history – is a mere thirty miles away. Gettysburg, Antietam, Winchester and Manassas provide plenty of opportunities to experience the Civil War, while places like Governors Island NY and Reading PA host weekends which bring the two world wars alive.

Reading is where I met my lovely tent mate, Camilla (known professionally as Lady Camille) – the personable friend I’m happily sharing cross-country drives with these days. It’s also where I met Don Sweet, David Suesz, Chuck Berrier, Bill Beam, and the rest of the men and women who make up the core of the 167th Photo Signal Company (Reenacted).

My first trip to Reading for the MAAM WWII Weekend was not unlike previous history-centric outings ~ save for the fact that I was there with a reporter’s notebook in hand, hoping to get a story I could share with the readers of a new news site called the Baltimore Post-Examiner. I got a story, all right, as I spoke with veterans of WWII. But I sensed a bit of hesitation from some in the reenacting community.

People who immerse themselves in a bygone era are leery of the press, as they often find their hobby and/or themselves fodder for flippant pencil pushers. No one wants to dedicate his time and resources to present an accurate representation of the men and women who served both at home and overseas, just to be portrayed in the media as a wacko who wants to run around in the woods playing army.

My solution to this problem was first, to be forthright in my reporting while eschewing editorial comment. That should be a given with any journalist. Sadly, of course, it is not.

A second solution was to have some fun while covering these stories, by taking a step back in time myself. Reenactors, I discovered, seem more at ease talking with a reporter when he has a press card stuck in the band of his felt fedora.

I was wearing my fedora and a 40s-styled linen suit on my second trip to Reading, when I met and interviewed Camille in 2014. She had driven down from New York with her camera to experience her first WWII history event. As a newbie, she told me, “History was my worst subject in high school, and now as an adult, it’s become my favorite. History is life. It may be past, but it existed and we’re all connected through it. I love it. After this experience, I will keep coming back to this event and bring more friends along.”

We became real friends shortly thereafter; and in time, by virtue of her photographic expertise, colleagues at the Post-Examiner.

Fast forward a few years, to February 2018, and Camille and I found ourselves at Ft. Indiantown Gap. By this point, we had been adopted (or were we drafted?) by the 167th. The reason for that move, I suspect, was simple: we had spent so much time hanging around the press tent at Reading, it was just easier for them to include us than to tell us to stay away.

It was our hope that, as members of the 167th, we would be able to cover the FIG Battle of the Bulge reenactment the way Ernest Hemingway and Lee Miller might have. Given the cold winter setting, I hoped my beret, trench coat and dark brown boots would be period enough clothing to get me embedded with a group of reenactors in the field. Sadly, an accident forced the cancellation of the big battle reenactment, leaving those who stayed to honor a few WWII veterans at the Saturday night USO dance.

But not to worry.

“You need to come to Ohio this summer for the D-Day Conneaut reenactment,” said David. “That’s like drinking water from a fire hose.”

D-Day Conneaut

David’s assessment, I would later discover, was spot on.

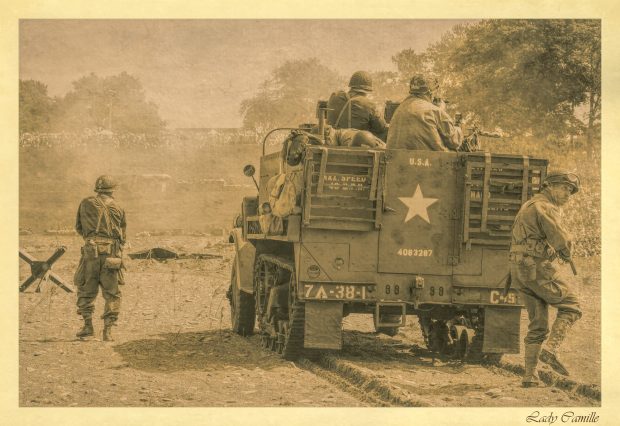

“D-Day Conneaut” is an annual recreation of June 6th, 1944. Held at Conneaut Township Park, along the eastern shore of Lake Erie, the event draws over 750 reenactors from the US and Canada who participate in the various living history activities. Nearly 20,000 spectators also descent on Conneaut during the two day event, as the 250 yard long beach and sloping adjacent terrain closely resemble Omaha Beach in Normandy, France. (UPDATE: Last year’s event had just over 1400 reenactors check in to participate and over 35,000 spectators in attendance. They also had just over 100 WWII veterans attend with their families .)

Where else could visitors perched on a hillside watch hundreds of American, Canadian, British, French and Polish reenactors storm an obstacle-covered beach while blank-filled canons, tanks, machine guns and mortars blasted away; then mix it up with elements of the Wehrmacht and Waffen SS reenacted?

Returning to 1944 early last summer, after a busy spring covering floods and other stories, Camille and I began in earnest to plan for an August trip to Conneaut. The guys with the 167th said they would help with costuming wherever they could. Still, we would need a footlocker full of gear if we were to hit the beach with the reenactors.

The first thing we did was take stock of what gear we already owned.

Camille had a few military-styled shirts, a campaign hat and pair of pants that might work at a distance. But they were certainly not faithful to the requisite WWII style. I owned a beret (oui), a pair of brown Doc Marteen boots (wrong), two surplus helmets (one WWII vintage – the other Vietnam), and a green web utility belt with a Vietnam-era canvas canteen cover.

I have no idea what happened to the canteen.

“What will we do?” asked Camille. “I don’t want to drive all the way to Ohio to sit on the hillside with the tourists.”

Neither did I, and neither did our editor Tim Maier, who offered to cover our traveling expenses — but only for an up-close story.

I reached out to our friends in the 167th.

Don said he had business to take care of and wouldn’t be making this trip. Neither was Bill, a Korean War veteran who prefers to stay close to home. David said he could provide what we’d need for staying in the group army tent, save for sleeping bags and pillows. Those particular items we’d have to cover during public hours with a green army blanket. David also suggested that Camille talk with two female members of the 167th about any “girls camping out” questions she might have.

Chuck said he could lend me an HBT jacket and offered to bring some war correspondent patches along. What we didn’t find online, Chuck assured me, would probably be available in the vendors’ area at Conneaut.

And so I began scouring the internet for any information I could glean about what the well-dressed war correspondent might have worn on D-Day.

Interestingly enough, the field seemed fairly wide-open. David would later remark that depicting a war correspondent was one of the easier portrayals.

Ernie Pyle is always pictured wearing regular G.I. gear, while Ernest Hemingway purchased safari clothing for his war corresponding from Abercrombie and Fitch. Edward R. Murrow can be seen in numerous pictures wearing Class A uniforms – addressing the world from a radio studio somewhere in London. And Robert Capa – who actually came ashore in the first wave at Omaha Beach – preferred paratrooper apparel; presumably because the extra large pockets worked well for stowing his cameras and film.

With this bit of knowledge, I began to build upon my measly stock of equipment. I had an Ike jacket made for me by a Chinese tailor, and found a pair of “pink” air corps trousers from an eBay seller in California. A guy in Seattle sold me a pair of wool field trousers. They had been cut down by an amateur, but enough material remained to accommodate my – umm – larger size.

I found a vintage army dress shirt at an antique mall up in Westminster, and purchased a wool field shirt from a vendor online. Smaller items, such as reproduction emblems, patches and belts were also found online. I replaced the missing canteen with vintage model from a local surplus store.

The rest would have to wait until we got to Conneaut.

Camille was stumped in her search – primarily because there is little in the way of reenacting wardrobe for women. We later learned that a lot of women in the hobby truly go old school and make their own military-styled clothing. Yet Camille was up for an adventure, reasoning that this might be her only chance to attend D-Day Conneaut.

“If I can’t go on the beach, I’ll just get you great photos from the spectator stands,” she said.

Ah, yes – a camera.

A Modern Day Robert Capa

Camille could certainly use modern equipment if she was shooting from the stands. But Betsy Bashore, who heads up the event at Conneaut, had been VERY clear in her correspondence with me that no one on the beach was permitted to use a modern digital camera unless it was somehow concealed from the watchful eyes of the general public.

There are a number of clever ways to accomplish this feat, but it seems to me that if you are going to the trouble to take hundreds of reenactors in WWII gear, transport them across Lake Erie in an assortment of landing craft, and then deposit them on the beach to face an army of equally authentically dressed German reenactors, the least a fledgling war correspondent could do was honor the setting by using a vintage camera. And by vintage, I don’t mean a dusty Instamatic or a Polaroid Swinger. Vintage would be one of the many options available, not only to pro photographers like Lee Miller and Robert Capa, but also the average serviceman in 1944.

To that end, I was able to borrow a 35mm Argus A3 from my good friend, award-winning photographer Bonnie Schupp.

Bonnie suggested I take the old Argus to Service Photo in Baltimore before trusting it in the field. The techs there were happy to clean the “dinosaur” for no charge, and suggested I use 100-speed black & white Kodak film. For developing, they pointed me to Brian Miller at Full Circle Fine Art Services, also in Baltimore.

Of course, I would have to get some printable pictures before bringing the film to Full Circle.

Thus marginally equipped, Camille and I made our way to Conneaut. We wondered if the expenses we were incurring would ultimately be worth it, and if we should ever try anything so ambitious again.

Arriving midday Friday, we had to negotiate a few reenactor army snafus, if we were going to be able to cover the event from the midst of the action on Saturday.

I thought I had made it clear via email correspondence who we were and what we wanted to do with this story. Apparently not, but after explaining that our boss would not be happy if the only thing we returned with was a souvenir tee-shirt, accommodations were made to get Camille and I onto the beach.

Along with Betsy, Brittany Gnizak, Robert Trumbull, Wayne Heim and several others in the chain of command worked fairly quickly to make it happen.

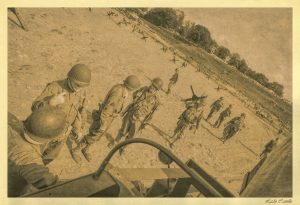

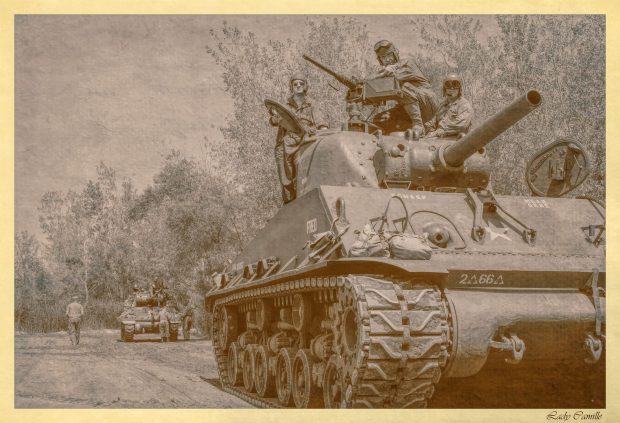

For Camille, accommodations meant she would be riding as part of a half-track crew with the 6th Armored Division (Reenacted).

I would be going ashore in the last wave with an infantry platoon aboard a vintage duck boat.

In the hours leading up to the big event, Camille and I busied ourselves with reporter duties and battle preparations. It was interesting to watch men line up for breakfast with shovel-sized spoons and tin mess kits in their hands.

I spoke for a bit about reenacting with Morgan Loud and his sister Raquel – two 167th tent mates who really shine when cutting a rug at the USO-styled hangar dances. The pair would remain dressed in vintage clothing right until the battle segments were over for the day, then slip into period-correct swimwear for a refreshing dip in Lake Erie.

We still had a little shopping to do, so Camille and I made our way to the vendor area. The two most important items I was still lacking were a garrison cap and a pair of leggings. I had actually purchased leggings before I left Baltimore but discovered too late that they were a size too small. Not-to-worry. They fit Camille just fine, and I learned a few tricks while lacing her into them.

Camille made a purchase too – buying a pair of wool army trousers she was able to score for fifteen dollars at the encampment flea market. They were a men’s sized small, but even so were pretty baggy on her petite frame. I assured her she looked fine and could always have them tailored when she got back to New York.

Zero Hour

At the appointed hour, we grabbed our helmets and cameras and made our way to join our designated groups. To pass the time, I helped one reenactor load hundreds of rounds of blank ammunition into a stack of box magazines. The beach was well out of sight, but one could hear tank engines start to rev. There was also engine noise aloft, as warplanes filled the sky above us.

The German reenactors were in place as the battle event began to unfold. Camille and her half-track hosts were in the woods just to the north of the beach at “Normandy.” The landing craft were taking on Allied troops at a secluded spot south of the impending action.

Event wranglers began bringing platoons down to the staging beach, perhaps 30-40 reenactors at a time. Along the way, all stopped for doughnuts and lemonade – courtesy of a Red Cross reenactment group. We also picked up earplugs and were constantly reminded to hydrate.

Two medic reenactors walked through the ranks with spare canteens. I took a swig from my surplus store find for good measure.

It tasted like the English Channel.

Since I was in one of the last groups to embark from the staging area, my initial view of the battle in progress was from a rocking boat on the lake.

Riding in a duck boat is somewhat less romantic than hitting the beach via the drop-down door of a landing craft. Access to and from the duck boat was by a rudely cobbled wooden ladder. I held onto several Garand rifles while my shipmates climbed aboard. But once on the beach, it was all business, as officers barked orders to the reenactment army.

The first order was to move out quickly and keep our heads low. The Germans may have been firing blanks, but who wants to watch a bobble-headed brigade leaping across the beach like carefree extras in a Coppertone commercial?

The distance from the shore to the German entrenchments was about 200 yards. That doesn’t sound like much until you are trying to run it through ankle-deep sand while wearing a wool uniform, combat boots, a utility belt and three lbs of steel on your head.

Luckily, we only had to run for about the first 100 yards. For the next 50 yards, we got to crawl on our bellies.

One thing you discover when forced to crawl in such a manner is that you really can’t see a thing from below your helmet without bringing your head up into the world’s most uncomfortable yoga pose. And yet, all around me, reenactors were somehow assuming an operational prone position long enough to fire a few shots at the enemy in the hills before crawling ever onward.

As I continued to crawl, the platoon I was assigned to made a break forward to a sand breastwork. I got there just as the order was about to be given to charge the final distance. Thirty yards ahead the German troops opened up with all they had.

Even with earplugs firmly in place, the sound of the faux fire-fight was tremendous. I began to understand the plight of warriors who returned from battle with the moniker “shell-shocked.”

Just as the platoon was cresting the breastworks, I shot the last frame with my antique camera. From that point, until the battle ended about 20 minutes later, I was simply an embedded spectator.

I would later learn that Camille’s afternoon with the 6th Armored Division included some hands-on experience firing vintage weapons.

“When I get home, I’m going to look into taking a gun safety course. A retired cop I know has volunteered to help, so I think I’ll take him up on that offer,” she said.

As for attending future events in uniform, Camille laid that question to rest.

“I’ve been bitten,” she smilingly exclaimed. “Let’s get the rest of our WWII gear together.”

The rest of our gear means not only filling out our uniform needs, but also period attire for attending the big band dances which end many WWII events. Combat boots are fine for the field but incredibly awkward for dancing to Moonlight Serenade.

Then too, “the rest of our gear” may also mean purchasing a couple of Argus A3 cameras.

Never having used such a camera, I had no idea how my pics would turn out. But once they were developed at Full Circle, Brian Miller described the lot as “very Capa-esque.”

A true compliment and exactly what I was going for.

During the course of my career as a reporter, I have spoken with hundreds of veterans – men and women who served everywhere from Africa, Europe, and the Pacific – to Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq, and during a Cold War which has really never come to an end. One can sincerely appreciate the courage of these people, who willingly stepped into harm’s way. But there is a level of empathy which may only be gleaned by flying in a B-17 or a SNJ-2; by stepping aboard a liberty ship like the John W. Brown or a YP boat with Annapolis midshipmen; by riding in a noisy half-track or crawling across an obstacle-strewn beach.

Perhaps that is the reason most reporters don’t “get” what living history is all about.

So yes, a couple of weeks from now, Camille and I may be spending two nights in a canvas tent, somewhere in wind-swept Pennsylvania, covering another wintry Battle of the Bulge event. She will don her baggy wool pants and trench coat, and I’ll button my field jacket against the cold.

And with any luck, we’ll come back with an enjoyable story and a further appreciation for the hardships the Greatest Generation endured.

* * * * *

Please enjoy the following roundup of images from D-Day Conneaut 2018 by Lady Camille and Anthony C. Hayes.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”